Abstract

Objectives: This paper reflects on characteristics that have supported state-wide scale-up, implementation, program maintenance, monitoring and evaluation of the Healthy Children Initiative (HCI), and reports on how the HCI has become embedded into the policies and practices of primary schools and early childhood services in New South Wales (NSW), Australia.

Type of program: The HCI is a multistrategy, settings-based approach to prevent childhood obesity. It currently comprises three flagship primary prevention programs that have been scaled up for delivery across NSW.

Method: This paper draws on the authors’ experiences implementing and evaluating the HCI to reflect on characteristics that have supported its state-wide scale-up, successful implementation, program maintenance, monitoring and evaluation.

Results: The ‘Munch & Move’ program, a flagship HCI program, promotes and supports organisational change in relation to healthy eating, physical activity and small-screen-time practices in early childhood services. The program has reached 89.0% (3348/3766) of all services in NSW (December 2017) (i.e. 89.0% of services have been trained and received support to implement the program). Another flagship program, the ‘Live Life Well @ School’ program, promotes and supports healthy eating and active living in primary schools. The program has reached 83.1% (2133/2566) of all primary schools (December 2017).

Lessons learnt: NSW has taken the long-term strategic approach, as recommended by the World Health Organization, and maintained continual investment in the prevention of childhood overweight and obesity. This unique delivery model of a state-wide coordinated approach in specific settings, including clear monitoring and reporting systems, has potential for application in other jurisdictions as well as other program contexts. Future directions must include a focus on more population groups, and attention to the food and physical environmental factors that affect active living and healthy eating.

Full text

Introduction

Childhood obesity is a significant public health concern in Australia and internationally.1 In New South Wales (NSW), the most populous state of Australia, the prevalence of overweight and obesity among all children aged 5–16 years is estimated to be 21.4% and has been stable since 2007.2 Childhood is an important period for establishing healthy eating and physical activity behaviours to reduce the risk of excessive weight gain.3

Whole-of-community and multistrategy approaches to obesity prevention are recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).4 However, few such initiatives have been conducted, particularly on a state-wide scale. Insights into successful approaches to implementing multistrategy, whole-of-population interventions, and the contextual factors that facilitate their execution, offer considerable opportunity to inform future efforts internationally.

The Healthy Children Initiative (HCI) is a government-funded, state-wide, comprehensive and equitable approach to reduce childhood obesity and improve the health of children in NSW. The HCI currently comprises three settings-based flagship primary prevention programs that were scaled up for delivery across NSW: ‘Munch & Move’ (early childhood services)5, ‘Live Life Well @ School’ (primary schools)6 and ‘Finish with the Right Stuff’ (FWRS) (junior community sport).7 These programs sought to change the institutional context and environments to support behavioural change. They were based on successful pilot programs implemented and evaluated as part of a regional prevention program – ‘Good4Kids’ – which found a significant decrease in the prevalence of overweight and obesity in the region.8 The HCI also includes a secondary prevention, community-based treatment program – ‘Go4Fun’ – for children aged 7–13 years who are above healthy weight, and their families.9

This paper reflects on characteristics that have supported state-wide scale-up, successful implementation, program maintenance, monitoring and evaluation of the HCI, based on the authors’ experiences implementing and evaluating the HCI.8 The implementation conditions described here are important for large-scale program implementation.4,10 The paper also reports on how the HCI has become embedded into the policies and practices of NSW primary schools and early childhood services – two of the key settings of the initiative. We begin by describing the policy and funding contexts, then reflect on key characteristics that supported implementation before focusing on the performance monitoring system, the Population Health Intervention Management System (PHIMS). Data on adoption of program practices by schools and early childhood services come from the purpose-built monitoring framework, with data entered by Local Health District (LHD) health promotion practitioners. Data from 2017 (the most recent full year of data) are compared with 2012 (the first full year of systematic data collection).

Implementation conditions for the Healthy Children Initiative

National and state policy and funding contexts

Sustained funding has been fundamental to the considerable and ongoing impact of childhood obesity prevention initiatives in NSW. In 2008, the national Council of Australian Governments entered into the National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health (NPAPH), which aimed to prevent the lifestyle-related risk factors that cause chronic disease. It was the largest single investment in chronic disease prevention in Australia. The agreement provided funding to each jurisdiction in Australia and committed $79 million to NSW, half of which was dedicated to the HCI. Each jurisdiction was able to design and deliver programs in ways that suited their local needs and complemented their jurisdictional policies and programs. In 2010, NSW started to deliver the HCI based on an implementation plan agreed with the Australian Government, which was revised in 2012.11

NSW had a strong existing commitment to the prevention of childhood obesity, having conducted an intersectoral childhood obesity summit in 2002, and funded a major regional childhood obesity intervention in one region of NSW.8 This intervention (Good4Kids) achieved high reach in the target organisations and led to a significant reduction in mean body mass index (BMI) among children age 5–15 years.8 The program logic assumed that implementation of evidence based practices and adoption of healthy policies in children’s settings would support healthy eating and physical activity behaviours in the short term, and reduce obesity prevalence in the medium to longer term.

In 2014, the NPAPH was defunded following a change in government. Nevertheless, this initial substantial funding had provided an opportunity to expand and scale up existing successful preventive health programs.12 Subsequently, NSW committed to fund the HCI under the cross-government NSW Healthy Eating and Active Living (HEAL) Strategy.13 The HEAL Strategy provided a framework for action and ensured that childhood overweight and obesity was retained as a key priority for NSW Government action.

Continuing government concern about childhood obesity was demonstrated by a parliamentary inquiry into childhood obesity in 2015. Ongoing government investment was ensured in 2015 when the NSW premier committed to a target of reducing the prevalence of childhood obesity by 5% in 10 years.14

Implementation and facilitation agency

The NSW Office of Preventive Health (OPH) was established in 2012 as a dedicated implementation agency to deliver and evaluate high-priority, state-wide preventive health programs to improve population health, reduce health inequities and reduce hospitalisations. It has a particular focus on childhood and adult obesity prevention. The OPH has been responsible for managing and evaluating the HCI since 2012.15 It provides critical centralised planning and coordination, and manages state-level partnerships. The role of the OPH has been to ensure standardised approaches, avoid duplication across NSW jurisdictions, and ensure the use of evidence to inform practice.

Local health promotion workforce

The NSW Health System comprises 15 LHDs, which employ a dedicated preventive health workforce. The workforce provides a professional infrastructure to rapidly deploy and facilitate the implementation of evidence based interventions across the state, including those associated with the HCI. Local health promotion staff deliver HCI programs on the ground, and target the most vulnerable populations in their community while maintaining program fidelity.16

Scaling-up of evidence based programs

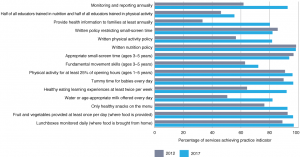

Several existing programs with good evidence of effectiveness were selected for implementation at scale. The Munch & Move program5 promotes and supports organisational change in relation to healthy eating, physical activity and small-screen-time practices (use of technologies such as tablets, phones and computers) in early childhood services. The program has reached (trained and participating) 89.0% (3348/3766) of all services in NSW (December 2017). Changes in program adoption over time are shown in Figure 1.

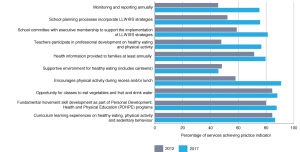

The Live Life Well @ School program6 promotes and supports healthy eating and active living in primary schools. It is a joint initiative of NSW Health and the NSW Department of Education, in consultation with the other education providers: Catholic Schools NSW and the NSW Association of Independent Schools. The program has reached (trained and participating) 83.1% (2133/2566) of all primary schools (December 2017). Changes in program adoption over time are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Munch & Move practice achievement over time (click to enlarge)

Figure 2. Live Life Well @ School (LLW@S) practice achievement over time (click to enlarge)

Finish with the Right Stuff (FWRS)7 aims to increase the proportion of children participating in community-based sport who drink water rather than sugary drinks before, during and after sport. The program also aims to improve the availability of healthy food and drink items in junior sports canteens. FWRS has reached (participating and have action plans) 198 clubs across NSW since 2016, across 15 sporting codes.

Go4Fun is an evidence based childhood obesity treatment program that has been translated from the UK’s MEND program17 as a community-based program for the Australian context. After a pilot with four health districts in 2009, implementation was scaled up for state-wide delivery from 2011.9 Go4Fun has reached (enrolled) 10 390 families across NSW (December 2017).

Program implementation monitoring

Monitoring of programs enables progress to be measured by assessing the reach and impact of the program, and provides a mechanism for accountability. Program adoption in HCI primary prevention programs is monitored through a set of indicators known as ‘practices’ related to nutrition, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and policy. The practices are monitored at least annually by LHD staff through direct contact with the school or service and according to a standard monitoring guide, which ensures consistent determination of achievement in sites across NSW.

An information management system, PHIMS, was commissioned to report HCI program data in real time. It is used by LHDs and the NSW Ministry of Health for performance monitoring, and by the OPH for overall program monitoring. PHIMS uses software that includes data entry, analysis and reporting functions. It was developed as a flexible, scalable and sustainable information technology solution, which also addresses access and confidentiality issues.18 The system has 150 users who monitor and report on more than 6500 intervention sites. Monitoring tracks the reach and adoption of these programs in vulnerable populations, as well as state-wide, to ensure that equity goals are being met.

Practice achievement in services and schools has significantly increased since monitoring commenced in 2012 (see Figures 1 and 2), with the greatest changes being for processes such as providing health information to families. Implementation and outcome data for Go4Fun and FWRS are recorded in other data systems.

Performance monitoring

HCI program funding is tied to performance targets built into the Service Level Agreements between the Ministry of Health and each LHD.19 Chief executives of each LHD are required to participate in quarterly performance reviews against their annual Service Level Agreement. The data used for performance monitoring of HCI programs are extracted from the PHIMS and the Go4Fun data systems to report on program reach and adoption for Munch & Move and Live Life Well @ School within each LHD. Key performance indicators for Go4Fun relate to enrolments and completion rates.

Discussion

The state-level investment in Good4Kids meant that evidence based community programs for childhood obesity prevention were available for dissemination. The positive political and funding context created by the NPAPH enabled the scaling-up of these programs and reciprocal partnerships with local health promotion practitioners across the state. The creation of the OPH as a dedicated implementation agency facilitates a coordinated state-wide approach that supports the capacities and focus of the existing health promotion workforce. The settings-based approach of HCI programs allows LHDs to establish and foster local partnerships with children’s organisations and build the capacity of these partner organisations to embed health promotion activities into everyday practice. The high population reach of key programs such as Munch & Move, Live Life Well @ School and Go4Fun are evidence of the success of the coordinated but locally flexible approach.

Performance monitoring contributes to LHD accountability, provides feedback to inform local HCI program delivery, and underscores the importance of the program at both state and local levels. It also contributes to a dialogue around ongoing investment in childhood obesity prevention in LHDs.

This paper draws on perspectives of senior staff involved with implementation, and we acknowledge the limitations of this and the risk of bias.

Conclusions

NSW has taken the long-term strategic approach, as recommended by WHO, and maintained continual investment in the prevention of childhood overweight and obesity. Halting the increase in childhood overweight and obesity in NSW has been achieved only after substantial scaled-up government investment in a range of obesity prevention and management programs for children in the early childhood and primary school years. This successful delivery model of a state-wide coordinated approach has potential for application in other jurisdictions, as well as in other program contexts. Future directions must include a focus on more population groups, and attention to the food and physical environmental factors that affect active living and healthy eating.

Acknowledgements

Many people have made significant contributions to the HCI including John Wiggers, Andy Bravo, Kym Buffett, Amanda Green, Nirmala Pimenta, Debra Welsby, Shay Saleh, Santosh Khanal, Vincy Li, Louise Farrell, Bev Lloyd, Leah Choi, Marc Davies, Lily Henderson, Nick Petrunoff, Deborah Radvan and LHD staff.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, commissioned.

Copyright:

© 2019 Innes-Hughes et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. A Picture of Overweight and Obesity in Australia 2017. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2017 [cited 2019 Jan 23]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/172fba28-785e-4a08-ab37-2da3bbae40b8/aihw-phe-216.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- 2. HealthStats NSW. Overweight and obesity in children. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2018 [cited 2019 Feb 4]. Available from: www.healthstats.nsw.gov.au/Indicator/beh_bmikid_cat

- 3. Wen LM, Baur LA, Simpson JM, Rissel C, Wardle K and Flood VM. Effectiveness of home based early intervention on children's BMI at age 2: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e3732. CrossRef | PubMed

- 4. World Health Organization. Report of the commission on ending childhood obesity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 [cited 2019 Jan 23]. Available from: www.who.int/end-childhood-obesity/publications/echo-report/en/

- 5. Lockeridge A, Innes-Hughes C, O’Hara BJ, McGill B and Rissel C. Munch & Move: evidence and evaluation summary. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2015 [cited 2019 Jan 23]. Available from: www.health.nsw.gov.au/heal/Publications/munch-move-evaluation-summary.pdf

- 6. Bravo A, Innes-Hughes C, O’Hara BJ, McGill B and Rissel C. Live Life Well @ School: evidence and evaluation summary 2008–2013. North Sydney NSW Ministry of Health; 2015 [cited 2019 Jan 23]. Available from: www.health.nsw.gov.au/heal/Pages/[email protected]

- 7. NSW Ministry of Health. Finish With The Right Stuff. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health [cited 2018Jul 19]. Available from: www.rightstuff.health.nsw.gov.au

- 8. Wiggers J, Wolfenden L, Campbell E, et al. Good for kids, good for life: 2006–2010 evaluation report. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2013 [cited 2019 Jan 23]. Available from: www.health.nsw.gov.au/research/Publications/good-for-kids.pdf

- 9. Henderson L, Lukeis S, O’Hara BJ, McGill B, Innes-Hughes C and Rissel C. Go4Fun evidence and evaluation summary: 2011–2015. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2015 [cited 2019 Jan 23]. Available from: www.preventivehealth.net.au/uploads/2/3/5/3/23537344/go4fun_report_2011-15_art_web.pdf

- 10. Milat A, King L, Bauman A and Redman S. The concept of scalability: increasing the scale and potential adoption of health promotion interventions into policy and practice. Health Promot Int. 2013;28:285–98. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. NSW Ministry of Health. Implementation plan for the Healthy Children Initiative; 2012 Dec [cited 2018 Jul 19]. Available from: www.federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/content/npa/health/_archive/healthy_workers/healthy_children/NSW_IP_2013.pdf

- 12. Wutzke S, Morrice E, Benton M, Milat A, Russell L and Wilson A. Australia's national partnership agreement on preventive health: critical reflections from states and territories. Health Promot J Austr. 2018;29:228–35. CrossRef | PubMed

- 13. NSW Ministry of Health. NSW Healthy eating and living strategy: preventing overweight and obesity in New South Wales 2013–2018. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2013 [cited 2019 Jan 23]. Available from: www.health.nsw.gov.au/heal/publications/nsw-healthy-eating-strategy.pdf

- 14. NSW Government. Sydney: State of New South Wales Department of Premier and Cabinet; 2017. Premier's priorities: tackling childhood obesity; 2018 Sep 10 [cited 2018 Jul 19]; [about 5 screens]. Available from: www.nsw.gov.au/improving-nsw/premiers-priorities/tackling-childhood-obesity

- 15. NSW Office of Preventive Health. NSW Office of Preventive Health: the fifth year (2016–2017) in review. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2017 [cited 2019 Jan 23]. Available from: www.preventivehealth.net.au/uploads/2/3/5/3/23537344/nsw_office_preventive_health_fifth_year_in_review_2017.pdf

- 16. Innes-Hughes C, Bravo A, Buffett K, et al. NSW Healthy Children Initiative: the first five years July 2011–June 2016. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2017 [cited 2019 Jan 23]. Available from: www.health.nsw.gov.au/heal/Publications/HCI-report.pdf

- 17. Sacher PM, Kolotourou M, Chadwick PM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the MEND program: a family‐based community intervention for childhood obesity. Obesity. 2010;18:S62–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 18. Conte K, Groen S, Loblay V, et al. Dynamics behind the scale up of evidence-based obesity prevention: protocol for a multi-site case study of an electronic implementation monitoring system in health promotion practice. Implementat Sci. 2017;12:146. CrossRef | PubMed

- 19. Farrell L, Lloyd B, Matthews R, Bravo A, Wiggers J and Rissel C. Applying a performance monitoring framework to increase reach and adoption of children's healthy eating and physical activity programs. Public Health Res Pract. 2014;25:e2511408. CrossRef | PubMed