Full text

Introduction

Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) provide culturally safe, holistic primary health care, and are well placed to address barriers experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples when accessing health services.1 These barriers include geographical proximity to services, racism, and transport issues.2 Across Australia, there are over 140 ACCHOs situated near where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples live.3 Driven by community leadership, documented strengths of ACCHOs include the ability to respond to the health and cultural needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.1,2

In 2017, Budja Budja Aboriginal Cooperative (BBAC) leadership identified that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in the region, were experiencing barriers to accessing the BBAC clinic, located in the small rural Victorian town of Halls Gap. BBAC is an ACCHO situated on the lands of the traditional owners, the Djab Wurrung and Jardwadjali Peoples, in Halls Gap, which is classified as Modified Monash Model category 5 in terms of rurality.4 Barriers to accessing the clinic included transport and finances, which are well established in the literature and are attributed to the distance required to travel to the clinic.2

Through an internally administered feasibility study that outlined many options and engaged with the perspectives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members and key stakeholders, it was identified that a mobile clinic model of service delivery would be appropriate. Funding was received from BBAC, Deakin University, and the National Indigenous Australians Agency, with additional funding support for a Mobile Clinic Coordinator obtained from the Western Victorian Primary Health Network. The Tulku wan Wininn mobile clinic (meaning ‘health to you’ in Djab Wurrung language) was launched in July 2019 and involved an equipped mobile van delivering general practitioner (GP), allied health (including optometry and audiology), and practice nurse clinical services to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients, including school students. Services were delivered across the ACCHO geographical region on a rotating basis. This report describes the characteristics of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients who accessed the Tulku wan Wininn mobile clinic and the frequency of consultations during the first 2 years of implementation, using health service data.

Methods

De-identified health service data from July 2019 to June 2021 was extracted from Pen CS Clinical Audit Tool (PEN CAT) and medical software program Medical Director by a designated BBAC employee, as per the principles of data sovereignty stipulated in a research data management plan (e.g., acknowledging the ACCHO as the custodians of health service data and the importance of the ACCHO in managing data extraction due to this).5 The extracted de-identified consultation and client data included gender, age, postcode, and consultation frequency. Service data was analysed descriptively using Microsoft Excel (v. 2016) by Deakin Rural Health (DRH), Deakin University’s Department of Rural Health, funded by the Rural Multidisciplinary Training Program, and academic partner of BBAC.6 Researchers included Aboriginal researchers who provided cultural guidance and non-Indigenous researchers. Reflexive practice in the form of de-briefs between researchers to critically examine different worldviews and how this shaped the research approach was inherent to the research process.7

Ethics approval

The evaluation of the Tulku wan Wininn received ethical approval from the Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (DUHREC 2019-432) and Budja Budja Aboriginal Cooperative, who provided a letter of support for the evaluation.

Results

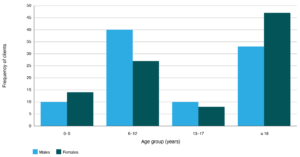

From July 2019 to June 2021, 75 new Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients were registered with BBAC through the Tulku wan Wininn mobile clinic (a 48% increase from July 2019 pre-implementation). Of the Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients accessing the mobile clinic for whom demographic data was available (n = 189 clients, n=564 consultations), 51% were female, and 49% male. Primary health care services provided through the mobile clinic were delivered to clients across the lifespan, with 42% (n = 80) of clients aged 18 years or older and the remaining 58% (n = 109) aged under 18 years (0–5 years n = 24, 13%; 6–12 years n = 67, 35%; 13–17 years n = 18, 10%, respectively) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander client age groups (click figure to enlarge)

A total of 564 consultations were provided to these clients, with the highest proportion delivered to adults (n = 310, 55%), followed by children aged 6–12 years (n = 144, 26%), children aged 0–5 years (n = 63, 11%), and young people aged 13–17 years (n = 47, 8%). The majority of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients accessing the mobile clinic (n = 174, 92%) resided in in two postal areas that cover the medium rural towns (Modified Monash Model 4)4 of Ararat and Stawell. Ararat and Stawell experience high levels of socioeconomic disadvantage as indicated by the Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD) (deciles 2 and 1, respectively).8

Discussion

Although subsequent evaluations are planned, this report provides preliminary findings about Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients accessing the Tulku wan Wininn mobile clinic during the first two years of implementation in a rural ACCHO. Further, this report contributes to addressing gaps in the literature around the utilisation of mobile primary care clinics by Indigenous Peoples internationally.9 Key findings include that the Tulku wan Wininn mobile clinic is a promising model of service delivery to expand the reach of an ACCHO. The mobile clinic provided primary health care services across the lifespan to clients residing in rural postcodes characterised by high levels of socioeconomic disadvantage who face significant barriers to accessing primary health care from a fixed location medical clinic. Findings have been expanded on by a qualitative process evaluation undertaken concurrently which identified considerations for early implementation of the mobile clinic, the importance of the mobile clinic in maintaining face-to-face services during COVID-19, acceptability as a model of service delivery, and requirements for maintaining the mobile clinic as a service delivery model.10

Although these findings are limited to the experience of a single rural ACCHO, they support the need for ACCHO-led models of service delivery to improve the accessibility of primary health care services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples – a need discussed elsewhere.9 There is a need for greater support for ACCHOs to implement targeted strategies to provide equitable healthcare for their communities and the need for system-wide change at a Federal and State healthcare level to achieve this.2,9,11

Conclusion

The Tulku wan Wininn mobile clinic is a promising model for delivering primary health care services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients of a rural ACCHO. Findings from the first two years of the service indicate it increased the reach of the BBAC, as demonstrated by the registration of new clients from nearby towns who had not previously accessed BBAC services. Further, the mobile clinic provided primary health care services across the lifespan, and to clients residing in postcodes characterised by high levels of socioeconomic and locational disadvantage. Policy and funding mechanisms supportive of ACCHOs innovating and implementing bespoke, localised, and equitable solutions to improve service accessibility and health outcomes for their communities are imperative.

Acknowledgements

This evaluation was supported by funding from the Australian Government under the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Program.

We acknowledge the Elders past, present and emerging, and the Djab Wurrung and Jardwadjali Peoples, the Traditional Owners of the land where the evaluation took place. We thank the BBAC leadership and staff, including Mobile Clinic Service Coordinator, Sarah Garton, and Aboriginal Health Worker trainee, Abbie Lovett, for their assistance in the evaluation.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, not commissioned.

Copyright:

© 2023 Beks et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Campbell MA, Hunt J, Scrimgeour DJ, Davey M, Jones V. Contribution of Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Services to improving Aboriginal health: an evidence review. Aust Health Rev. 2018;42:218–26. CrossRef | PubMed

- 2. Nolan-Isles D, Macniven R, Hunter K, Gwynn J, Lincoln M, Moir R, et al. Enablers and barriers to accessing healthcare services for Aboriginal people in New South Wales, Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:3014. CrossRef | PubMed

- 3. Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet. Map of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health/medical services. Western Australia: Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet; 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 12]. Available from: healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/key-resources/health-professionals/health-workers/map-of-aboriginal-and-islander-healthmedical-services/

- 4. Australian Government. Modified Monash Model. Canberra; Aust Govt Department of Health and Aged Care; 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 12]. Available from: www.health.gov.au/topics/rural-health-workforce/classifications/mmm

- 5. Carroll SR, Garba I, Figueroa-Rodríguez OL, Holbrook J, Lovett R, Materechera S, et al. The CARE principles for Indigenous data governance. Data Science Journal. 2020;19(1):43. CrossRef

- 6. Budja Budja Aboriginal Co-operative. Mobile clinic van – great outcomes and strong support from community and Deakin University. Victoria; BBAC; 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 12]. Available from: budjabudjacoop.org.au/new-mobile-clinical-health-van-april-2019/

- 7. Nilson C. A journey toward cultural competence: the role of researcher reflexivity in Indigenous research. J Transcult Nurs. 2017;28(2):119–27. CrossRef | PubMed

- 8. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of population and housing: socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016. Canberra: ABS; 2018 [cited 2022 Apr 12]. Available from: www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/by%20Subject/2033.0.55.001~2016~Main%20Features~IRSAD%20Interactive%20Map~16

- 9. Beks H, Ewing G, Charles JA, Mitchell F, Paradies Y, Clark RA, Versace VL. Mobile primary health care clinics for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States: a systematic scoping review. Int J Equity Health 2020;19(201):1–21. CrossRef | PubMed

- 10. Beks, H, Mitchell, F, Charles JA, McNamara KP, Versace VL. An aboriginal community-controlled health organization model of service delivery: qualitative process evaluation of the Tulku wan Wininn mobile clinic. International J Equity Health. 2022;21:163. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Beks H, Versace VL, Zwolak R, Chatfield T. Opportunities for further changes to the Medicare Benefits Schedule to support Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations. Aust Health Rev. 2022;46(2):170–2. CrossRef | PubMed