Abstract

Objective: The Australian Government Tackling Indigenous Smoking (TIS) program aims to reduce tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, delivering locally tailored health promotion messages, including promoting the Quitline. We aimed to analyse data on use of the Quitline by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples nationally, specifically in TIS and non-TIS areas.

Methods: We analysed usage of the Quitline in seven jurisdictions across Australia in areas with and without TIS teams (TIS areas and non-TIS areas respectively) between 2016–2020. Demographic and usage characteristics were quantified. Clients and referrals as a proportion of the current smoking population were calculated for each year, 2016–2020.

Results: From 2016–2020, 12 274 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were clients of the Quitline in included jurisdictions. Most (69%) clients were living in a TIS area. Two-thirds (66.4%) of referrals were from third‑party referrers rather than self-referrals. Overall, between 1.25% and 1.62% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who currently smoked were clients of Quitline (between 1.15–1.57% in TIS areas and 0.82–0.97% in non-TIS areas).

Conclusions: The Quitline provided smoking cessation support to approximately 2500–3000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients annually between 2016–2020. Referrals from third parties including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander services are an important pathway connecting community members to an evidenced-based cessation support service.

Full text

Introduction

Colonisation entrenched the use of commercial tobacco products among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and tobacco use is now the leading cause of early mortality.1-3 Ongoing experiences of colonisation and entrenched racism have resulted in the appropriation of economic resources and exclusion from the education system and the cash economy – well-documented risk factors for tobacco use. Despite this, and the tobacco industry’s ongoing promotion of its products, there have been significant declines in tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, with an absolute decrease in daily smoking prevalence of 9.8% – from 50% in 2004–05 to 40.2% in 2018–19.4 Quitting smoking at any age reduces the risk of mortality compared to continuing to smoke3, and ongoing investment is required to accelerate declining trends in smoking prevalence.

The Quitline is one component of a comprehensive approach to tobacco control. The Quitline is a telephone counselling service that provides behavioural interventions for smoking cessation (referred to as ‘the Quitline’ when describing the specific Australian-based quitline service), with some jurisdictional variation in running and administering quitlines across Australia.5 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people can access the ‘Aboriginal Quitline’, which is staffed by specialist Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander counsellors.6 The Quitline provides callers with information about the effects of smoking, benefits of quitting and pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation, and helps clients plan and implement a quit attempt using motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioural therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy.7

Telephone counselling has been shown to increase the success of quit attempts.8,9 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people referred to the Quitline were more likely to have made a quit attempt than those not referred.10 Quitlines have the potential for greater reach than face-to-face services at a comparatively lower cost5,8, which is particularly important given the landmass of Australia and distribution of the population.

Since 2010, the Tackling Indigenous Smoking (TIS) program has been funded by the Australian Government to reduce tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. TIS program funding has supported regional TIS teams to develop and deliver locally tailored health promotion activities.10 TIS also funded activities to improve the appropriateness of the Quitline for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. TIS teams and others may promote the Quitline and refer community members to the Quitline.6

Research from South Australia (SA) found that 3.6% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who smoked used the Quitline in 2010, which was comparable to rates among non-Indigenous people (3.7%).11 However, there are barriers to using the Quitline, which include access to a phone, a preference for face-to-face interventions, language barriers, a perceived lack of cultural appropriateness, lack of Quitline awareness, and low client motivation to quit.12 Further, Quitline referrals are impacted by health professionals’ beliefs and knowledge – such as awareness of and confidence referring to the Quitline and a belief that their role includes referring people to the Quitline.12

The Quitline provides a smoking cessation pathway for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, as part of a suite of cessation services. The purpose of this study was to describe the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who smoke who access and are referred to the Quitline nationally, over time and across the country. This study did not aim to assess the effectiveness of the Quitline in reducing smoking. Given the role TIS teams may play in promoting the Quitline, where possible, we also described Quitline access and referrals separately for people living in areas with TIS teams (TIS areas) and people living in areas without TIS teams (non-TIS areas). Although there is some information about the use of the Quitline by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples6,11,13, to our knowledge this is the first study to analyse Quitline data nationally and specifically in TIS and non-TIS areas.

Methods

Methodology

Our worldviews influence our perspectives, values, our study approach, and the interpretation of findings, and it is important to recognise our biases and Settler privilege.14 Settler privilege manifests through access to resources, educational and economic opportunities, social and political power that have been actively denied to Indigenous peoples. Our team draws on Aboriginal (SW) and Indigenous (RM) lived experience, and experience in public health, epidemiology and decolonising methodologies (all authors). We seek to uphold accountability to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and we humbly share this data with respect, to help improve program and service delivery. In attempting to mitigate and minimise the harms of ongoing coloniality and to optimise tobacco control, we acknowledge the critical importance of meaningful Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander engagement in development, implementation, and evaluation of tobacco control.15,16

This analysis forms part of the TIS program evaluation which was informed and guided by Thiitu Tharrmay; a national, representative Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research reference group. Thiitu Tharrmay provided guidance on study design, interpretation and dissemination of results. We used an integrated knowledge translation approach, sharing information and preliminary findings in an iterative manner with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge users, including Thiitu Tharrmay, the Quitlines across Australia, Aboriginal Quitline counsellors, and at TIS Jurisdictional Forums (annual forums bringing TIS teams together across states and territories).

Ethics and funding

This research upholds Indigenous ethical principles in conducting research and is consistent with National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Guidelines. Ethics approval was received from the Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee (#2019-654).

This work was undertaken as part of the TIS program evaluation (Health/1718/04008) by the Australian National University, funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care.

Data sources

Quitline data is held separately for each state and territory jurisdiction in Australia, with different administration and processes relating to data collection, storage and release. As such, the data available differs across jurisdictions. This study assessed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander client data from the Quitline in seven of eight Australian state or territory jurisdictions (with one jurisdiction excluded because it was not possible to identify whether clients were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples). Data from 2016–2020 is the primary period for analysis. Data was not available from each jurisdiction in each year: 2016–2017 data was sourced from five jurisdictions; 2018–2019 data was sourced from six jurisdictions; and 2020 data was sourced from all seven eligible jurisdictions.

We excluded years with partial data (2010 and 2021) and where there were fewer than half of all jurisdictions (2011–2015) from the main analysis. Individual jurisdictions were not identified in relation to their data, consistent with the conditions for data release.

Variables

Demographics

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander identity was the main criterion for client inclusion in this analysis. Demographic variables included: sex (male, female, other, unknown), and remoteness (using the definitions from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Australian Statistical Geography Standard17 which categorises remoteness areas on the basis of a measure of relative access to services, aggregated into: urban, regional and remote). Remoteness was derived from postcode where possible. If client postcode was missing, remoteness was derived from the location of the referring service when available.

TIS areas

Clients were deemed to be residing in a TIS area or non-TIS area based on residential postcode as determined following the method from Cohen et al.18 This approach draws from key informant consultations and Australian Government Department of Health documentation to define the geographic boundaries of TIS areas. Where TIS service boundaries did not align with postcode boundaries, we used a conservative approach, only considering a postcode as TIS if its entire area fell within a TIS service boundary. If a client postcode was missing and referred via a third party, TIS exposure was derived from the location of the referring service when available. Clients with missing location data that we could not approximate were still included in overall figures as part of ‘all clients’ or ‘all referrals’ but were excluded from TIS/non-TIS subgroups.

Outcomes

Key outcomes included: number of clients per year; number of referrals per year; and referral type. Referral types were categorised as self-referral (clients accessing Quitline directly), third-party referral (which was divided into three categories: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander services; other health services; and other); and unknown, based on the classifications used in the data supplied by each jurisdiction (See Appendix 1 for more information on referral source groupings, available from: hdl.handle.net/1885/311896).

Clients were defined as individuals who have had contact with Quitline. Contact could be a single phone call, or a program of ongoing support. Return clients were tracked across the datasets through use of a unique client ID. This analysis does not account for the intensity of contact, but investigates the number of people engaging with Quitline each year.

To manage the variation in included jurisdictions, we calculated clients per year and referrals per year as a proportion of the total number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who are current smokers in each of the included jurisdictions and in TIS and non-TIS areas. The current smoking population estimates for each jurisdiction in each year were either drawn from the ABS Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Health Surveys and Social Surveys conducted in the relevant year where available (see Appendix 2, available from: hdl.handle.net/1885/311896) using the ABS DataLab, or using linear interpolation to approximate the population between survey years. This was estimated separately for TIS, non-TIS and the total population (including participants with unknown location) for each jurisdiction and each year. If the Quitline data for a jurisdiction included people under the age of 18 years, then the 15+ population was used (five jurisdictions), while if the Quitline data included only adults, the 18+ population was used (two jurisdictions). Current smoking rather than daily smoking was selected as people smoking at any intensity may use the Quitline.

Statistical analysis

The data were cleaned and where possible harmonised across jurisdictions in Microsoft Excel (2016). Harmonisation involved merging and standardising data from each jurisdiction. For example, jurisdictions provided various data on referral type. We re-categorised this data into five broad groups: self; Indigenous health service or worker; other health service; other; and unknown; into which jurisdictional data could be categorised to enable comparison. As location, time and date data were provided in different formats these were similarly harmonised to calendar years and the remoteness and TIS/non-TIS variables.

We present the proportions of the respective variables (%), 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs, calculated using the standard error for proportions of SE = sqrt(p*(1–p)/n) (where p =proportion and n = total population), and number of calls, referrals and the reference current smoker population (n) for each year, 2016–2020.

These are calculated separately overall, as well as in TIS and non-TIS areas (aggregated from individual jurisdiction figures). Overall figures for all clients or all referrals indicate all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients, regardless of whether location (i.e. TIS, non-TIS and unknown location) data were available, to maximise use of all available information. As such, TIS and non-TIS figures do not total to the overall figures.

Due to data limitations and the inability to adjust for potential confounding factors, we limited the study to descriptive analyses and did not test for statistically significant difference between TIS/non-TIS areas or changes over time.

Results

Quitline usage overall: client and referral data, 2016–2020

The merged dataset for 2016 to 2020 contained 12 274 clients (Table 1). Of this total group, 8482 were living in a TIS area (69.1%), 2096 were living in a non-TIS area (17.1%), and 1696 (13.8%) had missing location data and were unable to be assigned to TIS or non-TIS areas. Between 2016 and 2020, 6319 clients were female (51.5%), 4337 were male (35.5%), 19 people did not have a sex option that applied for them (0.2%), and 1599 had missing data regarding sex (13.0%). Two jurisdictions did not capture remoteness (n = 6291), and remoteness data was missing for some clients within jurisdictions that did capture level-of-remoteness data (n = 1679). Of the 4307 clients with remoteness data, most lived in regional settings (n = 2436, 56.6%) followed by urban (n = 1634, 37.9%) and remote (n = 237, 5.5%).

From 2016 to 2020, there were 11 809 Quitline referrals received. About two-thirds of referrals from 2016–2020 were third-party referrals (n = 7841, 66.4%; self-referrals made up the remainder). Third-party referrers included Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health services (including but not limited to Aboriginal Health Workers and Tobacco Action Workers (TIS program staff)), non-Indigenous health service providers (such as general practitioners, nurses, dentists) and other third parties (such as community programs and research programs). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health services made up almost one-third (n = 2418, 30.8%) of third-party referrals.

Table 1. Quitline client and referral data 2016–2020, by year, location, sex and referral type

| 2016–2020 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |||||||

| Number of included jurisdictions | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 (6 for referrals) | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Number of clients | 12 274 | 100.0 | 1963 | 100.0 | 2167 | 100.0 | 2559 | 100.0 | 3016 | 100.0 | 2569 | 100.0 |

| TIS/Non-TIS area | ||||||||||||

| TIS | 8482 | 69.1 | 1406 | 71.6 | 1610 | 74.3 | 1706 | 66.7 | 2160 | 71.6 | 1600 | 62.3 |

| Non-TIS | 2096 | 17.1 | 346 | 17.6 | 382 | 17.6 | 430 | 16.8 | 466 | 15.5 | 472 | 18.4 |

| Unknown | 1696 | 13.8 | 211 | 10.7 | 175 | 8.1 | 423 | 16.5 | 390 | 12.9 | 497 | 19.3 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 4337 | 35.3 | 845 | 43.0 | 822 | 37.9 | 893 | 34.9 | 1031 | 34.2 | 746 | 29.0 |

| Female | 6319 | 51.5 | 1113 | 56.7 | 1291 | 59.6 | 1302 | 50.9 | 1393 | 46.2 | 1220 | 47.5 |

| Other | 19 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.1 | 6 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.1 | 8 | 0.3 |

| Unknown | 1599 | 13.0 | 5 | 0.3 | 52 | 2.4 | 358 | 14.0 | 589 | 19.5 | 595 | 23.2 |

| Remotenessa | ||||||||||||

| Urban | 1634 | 13.3 | 339 | 17.3 | 322 | 14.9 | 334 | 13.1 | 311 | 10.3 | 328 | 12.8 |

| Regional | 2436 | 19.8 | 427 | 21.8 | 446 | 20.6 | 517 | 20.2 | 512 | 17.0 | 534 | 20.8 |

| Remote | 237 | 1.9 | 51 | 2.6 | 57 | 2.6 | 30 | 1.2 | 56 | 1.9 | 43 | 1.7 |

| Unknown | 1679 | 13.7 | 139 | 7.1 | 189 | 8.7 | 500 | 19.5 | 424 | 14.1 | 427 | 16.6 |

| Referrals | 11 809 | 100.0 | 1828 | 100.0 | 2055 | 100.0 | 2483 | 100.0 | 2979 | 100.0 | 2464 | 100.0 |

| TIS | 7635 | 64.7 | 1219 | 66.7 | 1480 | 72.0 | 1479 | 59.6 | 2004 | 67.3 | 1453 | 59.0 |

| Non-TIS | 1903 | 16.1 | 262 | 14.3 | 319 | 15.5 | 397 | 16.0 | 472 | 15.8 | 453 | 18.4 |

| Unknown | 2271 | 19.2 | 347 | 19.0 | 256 | 12.5 | 607 | 24.4 | 503 | 16.9 | 558 | 22.6 |

| Referrals made by third partiesb | 7841 | 66.4 | 1221 | 66.8 | 1425 | 69.3 | 1589 | 64.0 | 2131 | 71.5 | 1475 | 59.9 |

| Third-party referrals made by Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander servicesc | 2418 | 30.8 | 198 | 16.2 | 364 | 25.5 | 460 | 28.9 | 1017 | 47.7 | 379 | 25.7 |

TIS = Tackling Indigenous Smoking program

a Two jurisdictions did not capture remoteness (missing data n = 6291).

b Percentages are calculated from total referrals.

c Percentages are calculated from total referrals made by third parties.

Quitline clients and referrals as a proportion of the current smoking population

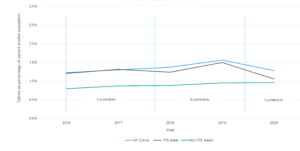

The proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who currently smoked and were clients of Quitline ranged from 1.22% in 2016 to 1.56% in 2019 (Figure 1). In TIS areas, the proportion of people who were current smokers that were clients of the Quitline each year was 1.06–1.50%, and 0.80–0.96% in non-TIS areas.

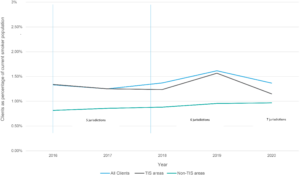

From 2016 to 2020, between 0.74% and 1.10% of the current smoking population were referred by third parties to the Quitline each year (Figure 2). In TIS areas between 0.64% and 1.08% of the current smoking population were referred to the Quitline by third parties. In non-TIS areas, between 0.42% and 0.65% of the current smoking population were referred to the Quitline by third parties.

Figure 1. Proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who currently smoke that were clients of Quitline, 2016–2020 (click to enlarge)

TIS = Tackling Indigenous Smoking program

Notes: 2016–17 data is sourced from 5 jurisdictions, 2018–2019 data is sourced from 6 jurisdictions, 2020 data is sourced from 7 jurisdictions.

Data on whether some clients were in a TIS/non-TIS area is unknown, therefore TIS + non-TIS will be less than total overall clients.

Figure 2. Proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who currently smoke referred by third parties to Quitline, 2016–2020 (click to enlarge)

Discussion

The Quitline provided smoking cessation support to more than 12 000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients from 2016 to 2020 in included jurisdictions, or approximately 2500–3000 clients annually. Overall, between 1.22% and 1.56% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who currently smoked were clients of Quitline (between 1.06–1.50% in TIS areas and between 0.80–0.96% in non-TIS areas). Between 0.74% and 1.10% of the current smoking population were referred by third parties to the Quitline each year (between 0.64–1.08% in TIS areas and between 0.42–0.65% in non-TIS areas). Here we calculated use of the Quitline as a proportion of all current smokers. Previous research shows that around seven in 10 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who smoke want to quit (70%19 to 76.6%18) and 48% made a quit attempt in the past year.19 As such, clients of the Quitline as a proportion of people who were current smokers and who are actively trying to quit may be higher than in the analysis.

Two-thirds of referrals were via third parties (as opposed to self-referrals), highlighting the important role of Tobacco Action Workers (TIS program staff) and health professionals in providing pathways to the Quitline. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health services were responsible for almost one-third of third-party referrals, showing leadership in tobacco control. These findings highlight the importance of building relationships20, which requires time, sustained long-term funding and was emphasised when engaging with Quitline staff, Quitline counsellors and TIS teams for this study. There are opportunities to actively encourage Quitline referrals from TIS teams, health professionals and other place-based supports (for example, Aboriginal Liaison Officers in hospitals, schools and the justice system). This should form part of a comprehensive tobacco control approach and routine care through provision of supports and tailored resources accessible to the healthcare sector and beyond.1,12

Levels of Quitline activity may have been influenced by awareness of the Quitline and the Aboriginal Quitline, acceptability of the Quitline to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and the activities of the Quitline and TIS teams. In 2019, there was a peak in Quitline activity in TIS areas that did not occur in non-TIS areas (1.50% vs 0.95%). Evidence suggests the use of incentives and health promotion events can help drive calls to Quitline.6,21 This is consistent with the experiences shared by Quitline staff during discussions as part of our integrated knowledge translation approach, including using special events, promotions and incentives to drive calls to the service.

Campaign characteristics, including message type and campaign reach, intensity and duration may influence campaign calls to action such as calls and referrals to Quitline.22,23 Further, messages that create an emotional response to the negative health effects of tobacco use are most effective at generating increased knowledge, beliefs, perceived effectiveness ratings and quitting behaviour. However, there is mixed evidence for information-centred approaches (e.g., ‘how to quit’) that do not generate negative emotions or use graphic imagery.22 Reduced mass media campaign activity during 2020 and various coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) lockdown periods likely impacted calls and referrals to the Quitline. Further, amplification of media messaging through community activities would have been substantially impacted due to COVID-19-related restrictions (e.g. lockdowns, event cancellations and travel bans). Absence of mass media campaign activity is strongly related to reduced quit attempts, including calls to quitlines.24,25 As we move through different stages of the pandemic with less intensive COVID-19 messaging, there are opportunities to increase comprehensive tobacco control activities. This includes campaign activities employing the types of messaging known to be most effective, that actively encourage quitting, calling the Quitline, and seeking local general practitioner or Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation cessation supports.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this work is the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership, guidance and direction in the overall program of research (TIS program evaluation). However, the enactment of Indigenous Data Sovereignty Principles (IDSov)26 concerning this analysis is limited. There were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander contributions to study conception and analysis, however the work was largely carried out by non-Indigenous researchers. Further, this work can potentially privilege non-Indigenous peoples and systems in the dissemination of findings (government evaluation report and peer-reviewed publication) and the Quitline data is held outside Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander contexts. We have attempted to uphold IDSov principles through engagement and guidance from Thiitu Tharrmay, Indigenous Quitline counsellors and TIS teams, helping to validate the findings and inform interpretation and dissemination.

Assessing usage of the Quitline and the impact of TIS is hindered by missing data, the lack of data availability prior to TIS program implementation in 2010, and inconsistent data available in the early years of the program. As such, the ability to assess changes over time related to the TIS program is limited and we have not been able to specifically test for significant differences between areas with and without TIS funding. Given we were unable to adjust for multiple likely confounding factors (such as age) and missing jurisdictional data in many years, we did not carry out any crude statistical tests, as these would be unreliable and misleading. Harmonisation between jurisdictions of the variables used (including remoteness, age categories, call types and referral types) would assist future research and evaluations. There is a specific need to be able to explore the impact of Quitline services, including the differences in intensity of programs through analysis of cessation outcome data. The publication of National Quitline Minimum Standards for the provision Quitline7 in 2021 is expected to result in improvements in record keeping overall, which will improve data quality and consistency. In particular, the Standards include a requirement that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identity is recorded in client management systems (3.5.4 b.), which would address a major limitation that saw one jurisdiction excluded from the analysis.

Conclusion

The Quitline provided smoking cessation support to approximately 2500–3000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients annually between 2016–2020. Referrals from third parties are an important pathway connecting community members to an evidenced-based, cessation support service. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander services are responsible for one-third of all third-party referrals to the Quitline. These new findings show that there is an opportunity to build and strengthen trusted relationships between community-based services, such as the TIS program and the Quitline, which will require adequate dedicated resourcing and funding. The findings provide an invaluable opportunity to assess Quitline function, and support continuous quality improvement to ultimately reduce smoking prevalence.

Acknowledgements

The authors humbly acknowledge, respect and thank all participants, Thiitu Tharrmay, Quitline counsellors, TIS teams, and all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples involved in this research. We acknowledge and respect all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their continuing connection to culture, land and seas.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, not commissioned

Copyright:

© 2024 Colonna et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Colonna E, Maddox R, Cohen R, Marmor A, Doery K, Thurber KA, et al. Review of tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin. 2020:20(2).

- 2. Maddox R, Waa A, Kelley L, Henderson PN, Blais G, Reading J, Lovett R. Commercial tobacco and Indigenous peoples: a stock take on Framework Convention on Tobacco Control progress. Tob Control. 2018;28(5):574–81. CrossRef | PubMed

- 3. Thurber KA, Banks E, Joshy G, Soga K, Marmor A, Benton G, et al. Tobacco smoking and mortality among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults in Australia. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50(3):942–54. CrossRef | PubMed

- 4. Maddox R, Thurber KA, Calma T, Banks E, Lovett R. Deadly news: the downward trend continues in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smoking 2004–19. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2020;44(6):449–50. CrossRef | PubMed

- 5. Greenhalgh EM, Stillman S, Ford C. Cessation assistance: telephone-and internet-based interventions. In Greenlagh EM, Scoll MM and Winstanley MH [editors]. Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues. Melbourne, Victoria: Cancer Council Victoria; 2022 [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-7-cessation/7-14-methods-services-and-products-for-quitting-te

- 6. Mitchell E, Bandara P, Smith V. Tackling Indigenous Smoking program: final evaluation report. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government Department of Health; 2018 [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/tackling-indigenous-smoking-program-final-evaluation-report-july-2018.pdf

- 7. Cancer Council Victoria. National minimum QuitlineTM standards for provision of services using the Quitline™ trademark in Australia. Melbourne, Victoria: Cancer Council Victoria; 2021 [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from:

www.cancervic.org.au/downloads/cpc/quit/National-Quitline-Minimum-Standards.pdf - 8. Hartmann‐Boyce J, Hong B, Livngstone-Banks J, Wheat H, Fanshawe TR. Additional behavioural support as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019(6);CD009670. CrossRef | PubMed

- 9. Kotz D, Brown J, West R. Prospective cohort study of the effectiveness of smoking cessation treatments used in the “Real World”. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(10):1360–67. CrossRef | PubMed

- 10. Tane MP, Hefler M, Thomas DP. An evaluation of the 'Yaka ŋarali'' Tackling Indigenous Smoking program in East Arnhem Land: Yolŋu people and their connection to ŋarali'. Health Promot J Aust. 2018; 29(1):10–17. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Cosh S, Maksimovic L, Ettridge K, Copley D, Bowden JA. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander utilisation of the Quitline service for smoking cessation in South Australia. Aust J Prim Health. 2013;19(2):113–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. Martin K, Dono J, Rigney N, Rayner J, Sparrow A, Miller C, et al. Barriers and facilitators for health professionals referring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tobacco smokers to the Quitline. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2017; 41(6):631–4. CrossRef | PubMed

- 13. Thomas DP, Bennet PT, Briggs VL, Couzos S, Hunt JM, Panaretto KS, et al. Smoking cessation advice and non-pharmacological support in a national sample of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smokers and ex-smokers. Med J Aust. 2015;202(10):S73–7. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. Watego C. Another day in the colony. Queensland: University of Queensland Press; 2021.

- 15. United Nations, United Nations declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples. Geneva: United Nations; 2007 [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf

- 16. World Health Organization, WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva: WHO; 2003 [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42811/9241591013.pdf?sequence=1

- 17. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Statistical Geography Standard. Canberra, ACT: ABS, 2023 [cited 2024 Feb 01]. Available from: www.abs.gov.au/statistics/statistical-geography/australian-statistical-geography-standard-asg

- 18. Cohen R, Maddox R, Sedgwick M, Thurber KA, Brinckley M-M, Barrett EM, Lovett R. Tobacco related attitudes and behaviours in relation to exposure to the Tackling Indigenous Smoking Program: evidence from the Mayi Kuwayu Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(20):10962. CrossRef | PubMed

- 19. Thomas DP, Davey M, Briggs VL, Borland R. Talking About The Smokes: summary and key findings. Med J Aust, 2015;202(10):S3–4. CrossRef | PubMed

- 20. Maddox R, Davey R, Cochrane T, Corbett J, Lovett R, van der Sterren A. The smoke ring: a mixed methods study. International Journal of Health Wellness and Society. 2015;5(2):55–8. CrossRef

- 21. Khan A, Green K, Khandaker G, Lawler S, Gartner C. The impact of a regional smoking cessation program on referrals and use of Quitline services in Queensland, Australia: a controlled interrupted time series analysis. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2021;14:100210. CrossRef | PubMed

- 22. Durkin S, Brennan E, Wakefield M. Mass media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among adults: an integrative review. Tob Control, 2012;21(2):127–38. CrossRef | PubMed

- 23. Durkin S, Bayly M, Brennan E, Biener L, Wakefield M. Fear, sadness and hope: which emotions maximize impact of anti-tobacco mass media advertisements among lower and higher SES groups? J Health Commun. 2018;23(5):445–61. CrossRef | PubMed

- 24. Siahpush M, Wakefield MJ, Spittal M, Durkin S. Antismoking television advertising and socioeconomic variations in calls to Quitline. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(4):298–301. CrossRef | PubMed

- 25. Miller CL, Wakefield M, Roberts L, Uptake and effectiveness of the Australian telephone quitline service in the context of a mass media campaign. Tob Control, 2003;12(Suppl 2):ii53–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 26. Maiam nayri Wingara Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Data Sovereignty Collective. Maiam nayri Wingara Indigenous data sovereignty principles. Australia: Maiam nayri Wingara; 2022 [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: www.maiamnayriwingara.org/mnw-principles