Abstract

Objectives and importance of study: In the public service context, co-design is novel and ever-expanding. Co-design brings together decision-makers and people impacted by a problem to unpack the problem and design solutions together. Government agencies are increasingly adopting co-design to understand and meet the unique needs of priority populations. While the literature illustrates a progressive uptake of co-design in service delivery, there is little evidence of co-design in policy development. We propose a qualitative study protocol to explore and synthesise the evidence (literary, experiential and theoretical) of co-design in public policy. This can inform a framework to guide policymakers who co-design health policy with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

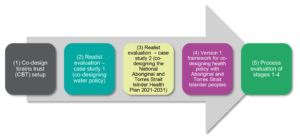

Methods: The study design is informed by a critical qualitative approach that comprises five successive stages. The study commences with the set-up of a co-design brains trust (CBT), comprising people with lived experience of being Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander who have either co-designed with public agencies and/or have health policymaking expertise (stage 1) The brains trust will play a key role in guiding the protocol’s methodology, data collection, reporting and co-designing a ‘Version 1’ framework to guide policymakers in co-designing health policy with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (the framework). Two realist evaluations will explore co-design in health policy settings to understand how co-design works for whom, under what circumstances, and how (stages 2 and 3) The findings of the realist evaluations will guide the CBT in developing the framework (stage 4). A process evaluation of the CBT setup and framework development will assess the degree to which the CBT achieved its intended objectives (stage 5).

Conclusion: The proposed study will produce much-needed evidence to guide policymakers to share decision-making power and privilege the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people when co-designing health policy. Learnings from this translational research will be shared via the CBT, academic papers, conference presentations and policy briefings.

Full text

Introduction

We need better policy

Policies need to change to better meet the complex and dynamic needs of priority populations.1 While policies impact population groups differently, priority populations are more likely to suffer extensive and enduring disadvantages.2 Such inequities can be traced back to policies underpinning unjust systems.3 Therefore, policy design is pivotal to shaping better outcomes for priority populations and should involve a deeper contextual understanding of the policy problems and aligning policy aims, strategies and tools to redress the problems.4

Traditional policy design

Traditional policy design reflects top-down government-led decision-making, where the problem definition and solution design are confined to a small group of people with decision-making power.5 In many ways, policymakers are often far removed from the policy problems they are trying to resolve. Therefore, first-hand or lived experience can be overlooked or misunderstood, leading to the embedding of uninformed assumptions (or no assumptions at all) into the fabric of policy design. Such transactional mechanisms reflect colonising structures, which have resulted in enduring power imbalances that undervalue or disregard priority populations’ decision-making capabilities.6,7 This misalignment neglects people’s lived realities and can lead to policy gaps that exacerbate the problem being addressed.8 For example, despite health promotion programs that encourage widespread uptake of clean drinking water, many rural and remote towns in New South Wales (NSW), Australia, have limited access to clean drinking water.9 In this context, the false assumption that every community in a high-income country like Australia has access to clean drinking water can undermine such health promotion efforts. Some policymakers realise that they cannot achieve lasting change on their own and acknowledge that priority populations have a better understanding of their own needs than anyone else.10

Promise of co-design

Co-design offers innovative ways for policymakers to engage with priority populations to cultivate a deeper comprehension of social problems and design solutions together.6,7 By including priority populations in decision-making, co-design counts diverse perspectives and experiences as ‘evidence’ to inform relevant solutions and drive lasting change.11 The literature highlights many benefits of co-design, including enhanced visibility of end-user experiences, improved public relations, strengthened customer relations, greater consumer satisfaction, better creativity, decreased risk of project failure and more innovative strategies.12

While co-design may not be the answer to every social problem, it has become a buzzword as public agencies increasingly claim to have co-designed their products, services and policies.13 Despite its ubiquity, tokenistic co-design efforts indicate a lack of understanding of what authentic co-design entails.7 Meaningfully engaging people with lived experience from the outset and throughout every phase of the design (i.e., problem posing, solution design, prototyping and evaluation) is a requisite of co-design.7 This fundamental hallmark can determine if something has been authentically co-designed. While each co-design process is unique, inclusivity stands as an essential cornerstone within every co-design undertaking.7 An exhaustive description of the features of co-design is beyond the scope of this article. However, it is worth recognising that effective co-designers establish, nurture and reaffirm the conditions for co-design.7 Conditions can include time, sponsorship, safe, collaborative spaces, supportive culture, participant remuneration, creative communication (e.g., language, art, role play) and readiness to privilege voices that are traditionally unheard or overlooked.13 Thus, co-design takes time and requires decision-makers to willingly share or hand over decision-making power to others. By situating lived experience front and centre, co-design can sometimes precipitate a ‘messy’, unpredictable and confronting terrain in comparison to traditional linear problem-solving approaches.7

Evidence for co-designing with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are a priority population in Australia. Co-design is garnering considerable traction as a method for addressing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health issues.14 Butler et al. comprehensively examined the evidence for co-designing health services with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.15 Principal themes derived from their analysis of 99 studies encompassed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership, a culturally grounded approach, respect, benefit to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, inclusive partnerships, and evidence-based decision-making.15 These discoveries informed the development of foundational principles and best practices for co-designing health services with First Nations Australians.16 National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation’s (NACCHO’s) co-designed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Plan emphasises the imperative for “…collective community-led action and sustained partnerships” to address the “…inequitable and avoidable differences’ experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer”.17 Dudgeon et al.’s Indigenous governance for suicide prevention in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: A guide for Primary Health Networks, advocates for an integrated co-design approach to suicide prevention.18

Policy design versus policy implementation

While evidence of co-design is predominantly found at the level of policy implementation (i.e., products, services, projects and programs), co-design in policymaking is lacking.13 Therefore, it is not clear how learnings from service design can be transferred to the policy design context. Our study explores health policy co-design to uncover practical learnings (e.g., principles, enablers and barriers) to guide policymakers in co-designing health policy with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy

The inequities that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience are well documented.19-22 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience specific problems that tend to co-exist across multiple government agencies at all jurisdictional levels. The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan23 demonstrates how the cultural determinants and social determinants of health encompass a myriad of portfolios beyond health. For example, the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are interconnected with cultural identity and linked to justice, social, education, environmental, infrastructure, and economic portfolios. However, traditionally siloed government structures often address complex policy problems in isolation. By only tackling a part of multifaceted problems, a system and lateral consideration of the interdependencies across jurisdictional, sectoral, corporate and community entities is absent. This has led to health policies that have not been fit for purpose, are unsustainable and/or imprudent8 and systems that have continued to perpetuate the significant health inequities experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. These conventional bureaucratic approaches need to shift to mechanisms that privilege the voices of and share decision-making power with people who are impacted by the problem.24

Terminology

Priority populations

Priority populations experience disadvantage as a result of their “…race and ethnicity, gender, sexual identity and orientation, disability status or special healthcare needs, and geographic location”.25 While ‘priority’ is synonymous with ‘vulnerable’, ‘minority’, ‘marginalised’ and ‘disadvantaged’, it supports a strengths-based discourse by emphasising an urgency with which we need to address the problems that priority populations experience.

Public policy

In this research, ‘policy’ denotes public policy. Policy is of extensive scope and has garnered varied definitions in academic discourse. We define policy as a system of laws to address a problem that is designed and enforced by public agencies.26

Research goal

Objective

Our research aims to examine co-design in health policy design. By exploring co-designed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy, this research aims to inform evidence-based co-design tools for health policymakers.

Methodology

Approach

Our qualitative research will explore the evidence of co-design in the development of health policy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Study governance

This research acknowledges and respects Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ self-determination and sovereignty. Thus, four Aboriginal governance structures are involved in guiding, designing and implementing this research. The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) provides the ethical and protocol compliance governance for this research as it relates to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The Djurali Research and Education Group Research Advisory Panel guides and provides Aboriginal governance to the project team. The CBT provides cultural and co-design expertise in designing the research implementation with the project team. This will embed Indigenous knowledge systems, perspectives and priorities in the research and findings dissemination. The project team implements the research in accordance with AIATSIS’ ethics and Djurali Research and Education Group Research Advisory Panel approval. The project team comprises researchers, policymakers and an Aboriginal elder who share a common purpose in advocating indigenising approaches that strengthen outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. All governance levels respectfully privilege Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ perspectives throughout this research by seeking their guidance, giving heavier weight to their valued contribution to decision-making (e.g., CBT selection) and respecting their cultural insights and advice. Meaningful engagement across all governance levels is critical to continually enhance our research. The AIATSIS granted ethical approval for this research (#REC-0161).

Study design

As illustrated in Figure 1, our study comprises five successive stages, namely: i) the setup of the CBT; ii) and iii) two realist evaluations; iv) Version 1 framework for co-designing health policy with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (the framework); and v) a process evaluation of the setup and framework development.

Figure 1. Protocol stages (click to enlarge figure)

Stage 1 – Co-design brains trust (CBT) setup

Aim

We will set up a CBT at the outset and empower its collective voice as co-researchers in this study. The CBT will be a small group comprising people with a diverse range of expertise in co-design and policymaking. As our co-researchers, the CBT will play a key role in shaping our protocol (i.e., critiquing, challenging and questioning selected parts within each stage), sharing insights, resources, and experiences, and co-designing the framework.

Design

Principles

Our project team will facilitate all CBT activities. Cultural safety, respect, reciprocity, transparency, accountability and sustainability will underpin our participatory approach to selecting, collaborating with and remunerating our CBT members. In line with the evidence, privileging the voices of people with lived experience will be championed in all CBT collaborations. This decision-making power balance will not reflect traditional decision-making mechanisms within the policy setting. Therefore, building the CBT’s capacity and capability will be key to ensure we support the elevation and integration of their voices, perspectives and experiences throughout the co-design process.7 Capacity-building will involve our promotion of strengths-based discourse in all CBT activities that frame the input of people with lived experience as evidence that enriches our way of doing things. Our early identification of relevant training and upskilling opportunities (e.g., cultural awareness, cultural safety, peer support) that can support the development of CBT members will be critical to fostering a culture of respect and trust within the CBT. We will foster strong two-way communication between CBT members and encourage feedback to continually enhance the protocol and CBT activities. CBT members’ (and realist evaluation participants’) safety will be a high priority of this research. We will appropriately manage all safety incidents, risks and issues, which can include recording (e.g., risk register), reporting (e.g., CBT yarning circles, other relevant platforms or stakeholders) and relevant follow-up (e.g., lessons-learned register). CBT members will be remunerated for their time and contribution to this research.

CBT inclusion criteria

We will scan an assortment of disciplines, sectors, and policy networks to shortlist, select and recruit CBT members. The CBT will comprise people with lived experience of: i) being an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander person and having participated in co-design activities; ii) co-design facilitation and/or research; and iii) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policymaking and related activities. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples will comprise 100% of CBT membership.

We will develop a CBT recruitment register informed by a scoping review of mostly online resources and networks to identify key people with relevant experience in co-design. Introductory meetings with these people (or groups) will inform the CBT selection process. We will seek recommendations for recognised co-design experts and facilitators. We will embrace opportunities to participate in co-design workshops and events to gain a deeper understanding of co-design in practice and engage with community connectors and gatekeepers. The inclusion criteria will inform the screening mechanism for shortlisting, selection and recruitment of CBT members.

Selection

Given the importance of relationships and connections in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research, we will employ snowball sampling, shortlist participants and resolve discrepancies by consensus. We will formally invite selected participants to join the CBT (which will involve a participant information sheet and informed consent form).

Logistics

We will consider procuring a range of digital tools to effectively manage CBT activities. These include shared documentation software and online communication tools to keep CBT members connected between yarning circles. We will manage all secretariat requirements and facilitate around eight CBT yarning circles over the 1.5-year protocol (and out-of-session collaborations as required).

Figure 2. Co-design brains trust (CBT) (click figure to enlarge)

Stages 2 and 3 – Realist evaluations

Aim

We will undertake two realist evaluations to explore the contextual realities of co-designing policy with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Both realist evaluations seek to address the question: “What works, for whom, under what circumstances, and how?”27

Design

The first realist evaluation looks at the role of co-design in water policy that impacts the availability of reliable drinking water in rural and remote communities in Australia. The second case study is premised on the co-design process underpinning the development of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan (2021–2031).23

The CBT will determine the extent of their involvement at each stage of the realist evaluations. The realist evaluations will investigate how co-design was used in designing each policy. Underpinned by a realist philosophy of science, the evaluations will assume that the policy problems are ‘real’ and the co-design element of each context will produce different outcomes in different circumstances. Therefore, we aim to understand how co-design might produce different outcomes in different contexts.

To achieve our aims, each realist evaluation will:

i) Establish an understanding of the policy context (policy aim, instruments, stakeholders, resources, etc.) by examining relevant literature and expert intelligence

ii) Construct evidence-based program theories (configured as ‘context-mechanism-outcome’ hypotheses) to be explored

iii) Recruit participants from the co-design processes

iv) Undertake semi-structured interviews with participants to capture real-world co-design experiences (including enablers, barriers, challenges, conditions, etc.)

v) Analyse the data using retroduction (i.e., using abductive reasoning to infer the most likely reason for observations)

vi) Test and refine the program theories (i.e., determine what works for whom, under what circumstances and how)

vii) Report the results according to RAMESES II quality and reporting standards28

vii) Conclude with a set of contextualised recommendations for policymakers.

Stage 4 – Version 1 framework for co-designing health policy with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Aim

The findings from Stages 1–3 will inform our collective framework development. Other evidence informing this work will include two realist evaluations of: i) atrial fibrillation screening of Indigenous communities in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the US29; and ii) improving breast cancer outcomes for Aboriginal women in Australia.30 This framework aims to equip policymakers with evidence-based guidelines and tools for co-designing health policy with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Design

While it is inappropriate to assume what this framework will look like, we expect it will at least include a set of guiding principles and practical tools for co-designing health policy with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The framework is intended to offer comprehensive guidance to equip policymakers, including pragmatic ways to set the conditions for co-design and prototyping. Mindful of the diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, our framework will elucidate the cultural and contextual considerations for meaningful co-design with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples that are linked to varying intersecting vulnerabilities.14

Stage 5 – Process evaluation

Aim

We will undertake a process evaluation of the CBT and the framework to determine whether (and the degree to which) the CBT’s activities have been implemented as intended and resulted in the proposed outcomes.

Design

Our process evaluation will:

i) Establish an understanding of the CBT objectives by reviewing relevant literature and expert intelligence (i.e., a logic model that outlines CBT’s planned inputs, outputs, impact and outcomes; a resources management plan that outlines how resources, including funding, are acquired, allocated, monitored and controlled, and a monitoring plan that tracks CBT progress against its targets)

ii) Collect data via semi-structured interviews and questionnaire with each CBT member (the questionnaire will involve CBT members being asked to rank each question twice on a 7-point Likert scale [once for relevance and once for validity]. and provide free text comments)

iii) Analyse the data to: a) assess the process’ quality (how well were the intended outputs implemented) and fidelity (were the intended outputs implemented as planned) of the CBT setup process; and b) explore the process’ reach, recruitment and context

iv) Assess the extent to which its intended outcomes were achieved within its specified timeframes

v) Report the findings of the process evaluation

vi) Conclude with recommendations for policymakers.

Results

We aim to publish our results in peer-reviewed journals, present them at research and public service forums, and they will culminate in a thesis. At least five publications are expected to emerge from this research project. Key criteria for journal selection will include relevance, appropriateness, open access, scientific rigour, peer-review process, ethical standards, reputation (of the editorial board, editorial quality) and indexing status. Our findings will also reach beyond journal platforms into health (and other) policymaking environments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. We will leverage our collective network to share the health policy co-design framework in health policy settings with policy champions in public agencies and across non-health sectors (e.g., education, justice). We will share our framework with co-design practitioners throughout our collective network. More importantly, we aim to create accessible resources (e.g., fact sheets, FAQs) for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to build their knowledge and understanding of policy co-design and their integral role in this process.

The CBT (and study participants, where relevant) will be invited to contribute to all publications and presentations. While our project team’s role is to undertake the research and advocate for the findings, the CBT, study participants and community are the authoritative custodians of this study’s data. Therefore, we will acknowledge and respect Indigenous Data Sovereignty and governance throughout this study, from the conceptualisation of data collection methods to reporting and results dissemination.

Limitations

We are aware that the requirements of our CBT (e.g., attending eight meetings over 1.5 years) may be demanding for some members. We expect continued engagement via online platforms will enhance the transparency and visibility of all CBT-related activities and decisions.

We are mindful that CBT members and study participants may not be able to continue throughout this study and address this risk by continual networking to recruit people who can enrich CBT activities throughout the study. While we expect the framework will add to the policy design landscape, we are cognisant that most public agencies face structural limitations and lack the capacity and capability to activate transformative change in policy design. Recruiting policymakers into the CBT and embedding testing and prototyping into the framework design will be critical to ensure that ideas are relevant in the real world.

Conclusion

Our study, as proposed in the above protocol, will consolidate the evidence and provide tools for policymakers to share decision-making power with and privilege the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples when co-designing health policy. Our translational research will be promoted via the CBT, academic papers, conference presentations, health policy training and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community forums.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge that the lands on which they live, work, and play were never ceded and, therefore, always were and always will be Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s lands. We pay our respects to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, the traditional custodians of these lands. We honour their profound cultural connection to land, sea, sky and community and commit to reconciliation for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in their homes, workplaces and social environments.

This article is based on research by author MF, funded by a joint PhD Project Specific Scholarship from Macquarie University and One Health Organisation (OHO). The authors acknowledge Macquarie University and OHO (Stephanie Clerc, Benjamin Haynes and Louise Barrett) for their financial support.

The authors also acknowledge Simone Sherriff, Research Fellow, The Poche Centre for Indigenous Health, University of Sydney, for her contribution to the manuscript drafting process.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, not commissioned.

Copyright:

© 2024 Fono et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Mueller B. Why public policies fail: policymaking under complexity. EconomiA. 2020;21(2):311–23. CrossRef

- 2. McLachlan RG, Gilfillan G, Gordon J. Deep and persistent disadvantage in Australia. Productivity Commission Staff Working Paper. Canberra ACT; Productivity Commission; 2013. [cited 2024 Apr 3]. Available from: www.pc.gov.au/research/supporting/deep-persistent-disadvantage/deep-persistent-disadvantage.pdf

- 3. Jagtap S. Co-design with marginalised people: designers’ perceptions of barriers and enablers. CoDesign. 2021;18(3):1–24. CrossRef

- 4. Howlett M. The criteria for effective policy design: character and context in policy instrument choice. Journal of Asian Public Policy. 2018;11(3):245–66. CrossRef

- 5. Bridge C. Citizen centric service in the Australian Department of Human Services: the Department's experience in engaging the community in co-design of government service delivery and developments in E-government services. Aust J Public Adm. 2012;71(2):167–77. CrossRef

- 6. Burkett I. An introduction to co-design. Sydney: Knode; 2012 [cited 2024 Apr 3]. Available from: www.yacwa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/An-Introduction-to-Co-Design-by-Ingrid-Burkett.pdf.

- 7. McKercher KA. Beyond sticky notes. Co-design for real: mindsets, methods, and movements, 1st Edn. Sydney, NSW: Beyond Sticky Notes; 2020.

- 8. Percy-Smith B. ‘You think you know?… you have no idea’: youth participation in health policy development. Health Education Research. 2007;22(6):879–94. CrossRef | PubMed

- 9. Perry C, Dimitropoulos Y, Skinner J, Bourke C, Miranda K, Cain E, et al. Availability of drinking water in rural and remote communities in New South Wales, Australia. Aust J Prim Health. 2022;28(2):125–30. CrossRef | PubMed

- 10. democracyCo. Australia: Democracyco; 2022 [cited 2024 Apr 3]. Available from: www.democracyco.com.au/about

- 11. Deserti A, Rizzo F, Smallman M. Experimenting with co-design in STI policy making. Policy Des Pract. 2020;3(2):135–49. CrossRef

- 12. Steen M, Manschot M, De Koning N. Benefits of co-design in service design projects. International Journal of Design. 2011;5(2):53–60. Article

- 13. Blomkamp E. The promise of co-design for public policy. Aust J Public Adm. 2018;77(4):729–43. CrossRef

- 14. Moll S, Wyndham-West M, Mulvale G, Park S, Buettgen A, Phoenix M, et al. Are you really doing ‘codesign’? Critical reflections when working with vulnerable populations. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e038339. CrossRef | PubMed

- 15. Butler T, Gall A, Garvey G, Ngampromwongse K, Hector D, Turnbull S, et al. A comprehensive review of optimal approaches to co-design in health with First Nations Australians. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23):16166. CrossRef | PubMed

- 16. Anderson K, Gall A, Butler T, Ngampromwongse K, Hector D, Turnbull S, et al. Development of key principles and best practices for co-design in health with First Nations Australians. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(1):147. CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cancer plan. Canberra, ACT: NACCHO; 2023 [cited 2024 Apr 2]. Available from: www.naccho.org.au/app/uploads/2024/02/NACCHO_CancerPlan_Oct2023_FA_online.pdf

- 18. Dudgeon P, Calma T, Milroy J, McPhee R, Darwin L., Von Helle S, Holland C. Indigenous governance for suicide prevention in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: a guide for Primary Health Networks. Perth, WA: Centre of Best Practice in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention and Black Dog Institute; 2018 [cited 2024 Apr 2]. Available from: cbpatsisp.wp1.cloudsites.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Indigenous-Governance-for-Suicide-Prevention-in-Aboriginal-and-Torres-Strait-Islander-Communities.pdf

- 19. Gwynne K, Cairnduff A. Applying collective impact to wicked problems in Aboriginal health. Metropolitan Universities. 2017;28(4). CrossRef

- 20. Bond CJ, Singh D. More than a refresh required for closing the gap of Indigenous health inequality. Med J Australia. 2020;212(5):198–9.e1. CrossRef | PubMed

- 21. O’Brien J, Fossey E, Palmer VJ. A scoping review of the use of co‐design methods with culturally and linguistically diverse communities to improve or adapt mental health services. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;29(1):1–17. CrossRef | PubMed

- 22. Cheng VWS, Piper SE, Ottavio A, Davenport TA, Hickie IB. Recommendations for designing health information technologies for mental health drawn from self-determination theory and co-design with culturally diverse populations: template analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e23502. CrossRef | PubMed

- 23. Department of Health and Aged Care. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government; 2022 [cited 2024 Apr 3]. Available from: www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2022/06/national-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-health-plan-2021-2031.pdf

- 24. Bradwell P, Marr S. Making the most of collaboration an international survey of public service co-design. Annual Review of Policy Design. 2017;5(1):1–27. Article

- 25. Rak K, Matthews AK, Peña G, Choure W, Ruiz RA, Morales S, et al. Priority populations toolkits: enhancing researcher readiness to work with priority populations. J Clin Transl Sci. 2019;4(1):28–35. CrossRef | PubMed

- 26. Hill MJ, Hupe PL. Implementing public policy: governance in theory and in practice. London: Sage; 2002.

- 27. Pawson R. The science of evaluation: a realist manifesto: London: Sage; 2013. CrossRef

- 28. Wong G, Westhorp G, Greenhalgh J, Manzano A, Jagosh J, Greenhalgh T. Quality and reporting standards, resources, training materials and information for realist evaluation: the RAMESES II project. Health Services and Delivery Research. 2017;5(28):1–108. CrossRef | PubMed

- 29. Nahdi S, Skinner J, Neubeck L, Freedman B, Gwynn J, Lochen M, et al. One size does not fit all–a realist review of screening for asymptomatic atrial fibrillation in Indigenous communities in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and United States. European Heart Journal. 2021;42(Supplement_1):ehab724.0461. CrossRef

- 30. Christie V, Rice M, Dracakis J, Green D, Amin J, Littlejohn K, et al. Improving breast cancer outcomes for Aboriginal women: a mixed-methods study protocol. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e048003. CrossRef | PubMed