Abstract

Background: Smoking during pregnancy is three times as common among Aboriginal women as non-Aboriginal women, with consequent higher rates of adverse health outcomes. Effective interventions to support Aboriginal women to quit smoking have not yet been identified.

Objectives: To assess the feasibility and acceptability of implementing a culturally tailored, intensive smoking cessation program, including contingency-based financial rewards (CBFR), for pregnant Aboriginal women.

Methods: The structured program included frequent support with individually tailored counselling, free nicotine replacement therapy, engagement with household members, specially developed resources, CBFR and peer support groups. It was implemented by three rural Aboriginal Maternal and Infant Health Services sites. Women were eligible if they or their partner were Aboriginal; and if they were: current smokers or had quit since becoming pregnant; ≥16 years old; at <20 weeks gestation; and locally resident. Data included demographics, obstetrics, initial smoking behaviour, program implementation and quitting behaviour. Self-reported quitting was confirmed by expired carbon monoxide (CO). Women and staff were interviewed about their experiences.

Results: Twenty-two of 38 eligible women (58%) enrolled in the program, with 19 (86%) remaining at the end of their pregnancy. The program was highly acceptable to both women and providers. Feasibility issues included challenges providing twice-weekly visits for 3 weeks and running fortnightly support groups. Of the 19 women who completed the program, 15 (79%) reported a quit attempt lasting ≥24 hours, and 8 (42%) were CO-confirmed as not smoking in late pregnancy. The rewards were perceived to help motivate women, but the key to successful quitting was considered to be the intensive support provided.

Conclusions: ‘Stop Smoking in its Tracks’ was acceptable and is likely to be feasible to implement with some modifications. The program should be tested in a larger study.

Full text

Introduction

In high-income countries, antenatal smoking is the most important modifiable cause of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including low birthweight, perinatal death and premature birth.1 Aboriginal mothers have higher rates of these problems than their non-Aboriginal peers2,3, and smoking is an independent risk factor.2

Despite some decrease4, antenatal smoking remains more than three times higher among Aboriginal women than non-Aboriginal women, with 44% of Aboriginal women smoking.3 Interventions to reduce antenatal smoking are effective in other populations5; however, effective interventions for pregnant Aboriginal Australian women have not yet been identified.5-7

We report findings from a small feasibility trial of a culturally tailored, intensive smoking cessation program, including contingency-based financial rewards (CBFR), for pregnant Aboriginal women, undertaken between June 2010 and May 2012. This was before the implementation of ‘Quit for New Life’, a smoking cessation program for women having an Aboriginal baby.

The smoking cessation program

Community reference group

A community reference group (CRG) of Aboriginal women, midwives and Aboriginal health workers (AHWs) guided this project to ensure it was conducted in a culturally secure manner.8 The CRG provided advice on all aspects of the project, including preliminary research, quitting program development, recruitment of services and women, data collection, and interpretation of findings.

The Stop Smoking in its Tracks (SST) program

Both the preliminary work to develop the program and the SST program are described in detail in the Supplementary File (available from: https://hdl.handle.net/2123/16909), as detailed descriptions are important to support replication.9 The SST program is described briefly here and incorporates best evidence. It was designed to be delivered by the Aboriginal Maternal Infant Health Services (AMIHS) midwife and AHWs, and included the following steps:

First visit:

- Assessing smoking status: At the first visit, the midwife explored the woman’s smoking status, nicotine dependence and previous quit attempts

- Discussing risks and benefits: Using a motivational approach, the team explored the woman’s understanding of the risks of smoking and benefits of quitting, and emphasised the benefits of quitting

- Advising smokers to quit: Women were advised to quit immediately for the sake of both mother and baby

- Exploring barriers to quitting: Women were assisted to identify smoking triggers, potential barriers, strategies to manage these, and other sources of support.

For women who wanted to quit:

- Contract to quit: Women were asked to commit by completing a simple contract stating their reasons and their willingness to try. The commitment contract was also signed by the provider

- Assessing expired carbon monoxide (CO): A Smokerlyzer was used to measure baseline expired CO and provide a visual reminder of the impact of smoking

- Household support: Household smoking patterns were explored and advice was provided on ways that household members could support the woman

- Confirmation and follow-up: Providers reaffirmed the woman’s decision to quit, congratulated her, then arranged follow-up 2–4 days later

- Educational material: Four brochures were developed: 1) ‘Reasons to quit’; 2) ‘How to manage quitting’; 3) ‘Household support’; and 4) ‘After the birth’. Other resources included fridge magnets, a tiny nappy for an extremely premature baby (a ‘premie nappy’) and stickers.

Subsequent visits:

- Frequency: Women were visited at home twice weekly for 3 weeks, weekly for 4 weeks, then fortnightly until the birth

- Content: At all visits, progress was assessed and positive feedback given with tailored support and advice. Women reporting successful quitting were congratulated and asked to blow in the Smokerlyzer for confirmation and to provide visual reinforcement of the benefits of quitting. Those with expired CO <6 parts per million (ppm) were given a reward voucher. If women had not yet succeeded, further tailored advice and encouragement were given

- Household members: Household members were advised on how to support the woman’s quit attempt. Where appropriate, they were also encouraged to quit smoking, with support

- Free nicotine replacement therapy (NRT): Intermittent forms of NRT were offered if women were unable to quit after two attempts.

CBFR:

- Immediate provision of CBFR: Women confirmed as abstinent were immediately given a reward voucher reimbursable for goods at participating businesses

- CBFR value: Rewards started at $10 and increased by $2 for each consecutive visit with confirmed abstinence, to $30 maximum.

Additional support:

- Postpartum support: For women who were not smoking at the end of pregnancy, the program was offered until 6 months postpartum, but this is not reported here because numbers were low

- Peer support groups: Fortnightly peer support groups were offered.

Other considerations:

- Women who had already quit: Women who quit during pregnancy before enrolling were immediately given their first reward (contingent on CO confirmation). This supported them in their nonsmoking status and avoided creating an incentive to delay quitting to be eligible for the program.10,11 They then followed the same program

- Women not wanting to quit: Women who did not initially want to quit continued to receive quitting advice at every standard antenatal visit. Those who later decided to try were enrolled in the program

- Training for staff: Staff received a structured 2-day training program with a detailed manual

- Strengths-based approach: A strengths-based approach was used by engaging with the CRG, and building on existing service infrastructure, relationships in the community and the community’s own strengths.

Aims

The aims of this evaluation were to assess the program’s acceptability to women and providers and the feasibility of implementation, and to consider suggested improvements. The aim was also to provide data for use in a larger trial.

Methods

Design and setting

The project was conducted with the New South Wales (NSW) AMIHS, which delivers care by community midwives and AHWs, with links to other services and the local Aboriginal community.12 The quitting program was implemented at three rural AMIHS sites for an average of 12 months each between June 2010 and May 2012. Initially, we planned two intervention and two control sites but, due to staffing difficulties at one intervention and one control site, these sites withdrew (available intervention site data is included in the analysis). The remaining control site was converted to an intervention site, and the control groups were dropped.

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees of the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW and the Greater Western Area Health Service.

Eligibility

Pregnant women receiving antenatal care at participating sites were eligible if they were:

- Aboriginal, or their partner was Aboriginal

- A current smoker (self-reported daily or occasional smoking) or recent quitter (since becoming pregnant)

- Aged ≥16 years

- At <20 weeks gestation

- Resident in the study area, and expecting to stay there for their pregnancy.

They were excluded if they were:

- Currently being treated for chemical dependency other than tobacco or alcohol

- Diagnosed with florid mental illness

- Unable to provide informed consent.

Recruitment and consent

During routine antenatal visits, the midwife assessed women’s eligibility. For eligible women, the team provided verbal and written explanations of the study and invited participation. Written consent was obtained.

Data collection

A recruitment log was maintained to assess eligibility and recruitment rates.

For all consenting women, a data collection form recorded demographic (date of birth, usual residence, Aboriginality of woman and partner); obstetric (date of first visit, parity, gestation); and initial smoking data (self-reported smoking, cigarettes smoked per day, level of dependency, previous quit attempts). At each visit, this form was used to record program implementation (counselling on specified topics, resources provided, identification of social supports, awarding of CBFR, offer and uptake of NRT, involvement of partner/household members) and quitting behaviour (requested quit support, made quit attempt(s), successfully quit, relapsed). Self-reported quit status was confirmed using the piCO+ Smokerlyzer; a cut-off of expired CO <6 ppm was considered nonsmoking. The CO level was recorded.

Women were interviewed in late pregnancy by a trained female Aboriginal research assistant using a semistructured interview guide to assess their experience of the program and suggested improvements.

Staff were interviewed at the end of the program (individually or in teams, according to preference) to explore their perceptions of the program’s acceptability and impact, their experiences implementing it and suggested improvements.

Data analysis

Data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet then imported into Stata Statistical Software (College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; Release 9) for analysis. Descriptive statistics relating to the aims were generated, including:

- Acceptability – enrolment and completion (remained in the program until the end of pregnancy) rates

- Feasibility – rates of implementation of key components

- Outcomes – self-reported quit attempt, self-reported quit lasting at least 24 hours, confirmed quit (CO <6 ppm) at any time, not smoking at 36 weeks gestation (CO <6 ppm).

All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were checked, then offered to participants for verification. Transcripts were read repeatedly by the first author, then analysed to identify key issues relating to acceptability, feasibility and suggested improvements.

Results

Characteristics of participants and acceptability

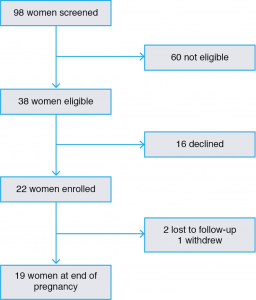

Twenty-two of 38 eligible women (58%) enrolled in the program. Among enrolled women, 19 (86%) remained in the program to the end of their pregnancy, two were lost to follow-up and one withdrew (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart showing participation in the study (click to enlarge)

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, Aboriginal status, gestation or smoking status between women who enrolled and those who declined.

Table 1. Characteristics of 19 women who completed the program

| Characteristic | Category | n |

| Age group (years) | <20 | 6 |

| 20–29 | 10 | |

| ≥30 | 3 | |

| Aboriginal status | Aboriginal | 17 |

| Non-Aboriginal (Aboriginal baby) | 2 | |

| Parity | Primiparous | 5 |

| 1–2 | 9 | |

| ≥2 | 5 | |

| Gestation at recruitment (weeks) | ≤12 | 9 |

| 13–20 | 10 | |

| Smoking status at recruitment | Current smoker | 15 |

| Recent quitter | 4 | |

| Cigarettes/day (current smokers) | ≤5 | 6 |

| >5 | 9 | |

| Minutes to first cigarette (current smokers) | ≤30 | 7 |

| >30 | 8 |

All the AMIHS teams viewed the program very positively, stating it was good to have a comprehensive program to offer. They considered the program well structured and that most women valued it. The resources were “at the right level” and useful as a prop for conversations. “The premie nappy made a huge impression, and the brochures that were for each stage … they were good resources, … I like using those with women.”

The Smokerlyzer was not always used at the first visit as intended, because there were some concerns that it was a “serious piece of equipment”. However, it was also perceived to increase women’s resolve to quit because it was highly visual and generated a strong emotional response. The staff liked having free NRT to offer because it was appreciated by women, some of whom tried it, although none used it for long. It was also good to offer to family members, because this made it easier to broach the topic of quitting.

Only one site ran the group program. This team enjoyed running the groups because the women seemed to find interacting with each other and discussing their experiences to be helpful. The manual and resources were helpful and made running the group sessions easy.

The rewards for quitting were well received and the staff considered them empowering. “I think the biggest word is proud. They were just so proud that they got enough vouchers to get a hair straightener or – one got a fridge.”

The staff did not think the program made women avoid them but, at one site, there was concern that they had to scale back the “smoking talk” for some women who had not managed to quit.

Thirteen women were interviewed. Their views of the program were positive and they appreciated the frequency of support, information provided, household support and free NRT. All women interviewed – even those who did not quit – mentioned that they valued the frequent support, and most mentioned this first: “… they’re really there to support you, … really go over your stresses with you and how else you can deal with it, … it seems like they really care”.

None of the participants spontaneously mentioned the rewards but, when asked, indicated that they were motivating and helpful, with no negative comments. Several women discussed the purchases they had made, or what they had planned to buy if they had succeeded.

Some women were reluctant to try NRT, but valued having it offered; others appreciated the opportunity to try different types. Several women also mentioned that free NRT for household members was helpful.

The visual aids (premie nappy, poster with cigarette contents, photos in brochures, Smokerlyzer) were commented on by several women as being motivating: “they show you all the stuff that’s in a cigarette and it really makes you want to stop” and “[The Smokerlyzer was] something to look forward to each week … knowing how low I was, was really motivating”.

Those who attended groups enjoyed them and usually attended regularly. They valued the opportunity to share stories, the activities offered and the information on strategies. “[Groups] relaxed you and took your mind off things that were really stressing you out … Just the little activities and meeting other people that were doing the same thing.”

Feasibility

Rates of implementation of the various components are shown in Table 2 for all participants, and for women who were current smokers at recruitment.

Table 2. Implementation of program components

| Program component | All participants (n = 19), n (%) | Women smoking at recruitment (n = 15), n (%) |

| Dependency recorded | 17 (89) | 14 (93) |

| Advised to quit now | 19 (100) | 15 (100) |

| Smokerlyzed | 14 (74) | 10 (67) |

| All resources given in first three visits | 14 (74) | 11 (73) |

| At least three visits in first 2 weeks | 11 (58) | 7 (47) |

| Woman offered NRT | 12 (63) | 11 (73) |

| Woman accepted NRT | 8 (42) | 8 (53) |

| Household offered NRTa | 6 (32) | 4 (27) |

| Household member accepted NRT | 4 (21) | 3 (20) |

| Attended at least one group session | 7 (37) | 4 (27) |

| Received at least one reward | 9 (47) | 5 (33) |

NRT = nicotine replacement therapy

a We did not collect data on household smoking behaviour, so cannot determine what proportion of households with smokers were offered NRT.

Although the AMIHS teams valued the program, they also found it challenging to implement without additional team capacity. One site withdrew because unrelated staffing issues meant they could not implement the program, and another site struggled to implement it fully because there was no AHW for most of the study period. Staff turnover meant the training had to be provided twice at both these sites. The remaining site had full and stable staffing (one midwife and one AHW) and implemented all components, although they still found the frequent visits in the first 3 weeks challenging, given the travel distances involved. This team commented that having two staff working together brought advantages of having different perspectives and approaches while sharing the responsibility, sense of purpose and successes.

Engaging some women was difficult, especially if they moved around. In general, partners were easier to involve than other household members, and partners were more likely to support the woman and make a quit attempt themselves.

The group program was only run at one site because other sites lacked capacity. Although the groups were well received among those who attended, they were challenging to coordinate. Staff had to collect the women from multiple dispersed locations because few women owned cars and there was no public transport. Conflicting priorities for the women and other events made group sessions difficult to schedule, and they were sometimes rescheduled at the last minute.

The staff found that the reward system and associated paperwork worked well. A total of 110 rewards were given to women, with a total value of $2300. Among women receiving rewards, the average value was $271 (range $56–$460). The staff reported that the rest of the program was easy to implement, including providing advice and support to women and their households.

Impact on smoking behaviour

Changes in smoking behaviour are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Smoking-related outcomes

| Outcome | All participants (n = 19), n (%) | Women smoking at recruitment (n = 15), n (%) |

| Self-reported quit attempt | 16 (84) | 12 (80) |

| Self-reported quit lasting at least 24 hours | 15 (79) | 11 (73) |

| CO-confirmed quit at any time | 11 (58) | 7 (47) |

| Abstinent in late pregnancy (CO-confirmed) | 8 (42) | 5 (33) |

CO = carbon monoxide

Most women made multiple attempts before successfully quitting. Relapses to smoking were followed by further quit attempts before becoming consistently abstinent. The combination of rewards and support was considered critical to success. The rewards motivated women to try, and the support helped them to keep trying and achieve success. “Just having the vouchers and that to offer them, I think that did lead a lot of women to make that decision easier.” Regarding the most powerful components: “I think the sustained visiting and phone calls. The fact that we were mentioning it all the time and how you’re going and trying to come up with things to help them cope”.

At least two of the women’s partners quit, and one mother and one father quit during their daughters’ pregnancies, with the free NRT credited as making a difference by the women interviewed.

Women who received at least three visits in the first 2 weeks were significantly more likely to be abstinent in late pregnancy than those who did not (64% vs 12.5%, χ2 4.9684, p = 0.026).

Suggested changes

All suggestions from the AMIHS teams related to their lack of capacity to sustain the program with existing resources. Suggestions included reducing the frequency of visits, dropping the group program or providing additional assistance to help with groups.

The idea of an additional dedicated worker to run the quitting program was discussed but was considered to be too complex. Rapport and engagement with women through the existing AMIHS program were considered to be critical, so any additional worker would need to be integrated into the AMIHS, not separate from it.

There were no suggestions for changes from participating women, who made comments such as “nothing could make it better, it’s all good”.

Discussion

This is the first study we are aware of to assess the acceptability and feasibility of using CBFR for smoking cessation among pregnant Aboriginal Australian women. However, SST was not just an incentives program but a comprehensive, intensive support program that was culturally tailored for Aboriginal women. The involvement of the CRG at every phase was crucial to ensuring that the program met the needs of Aboriginal women in a respectful manner. Partnering with the AMIHS program ensured that cessation support was provided within a framework of comprehensive pregnancy care that addressed social and cultural needs, by a team that had an ongoing relationship with the women.

The program was well received, with a reasonable enrolment rate (58%) and excellent completion rate (86%). The high completion rate and the expressed views of the women interviewed indicate that women appreciated the intensive support they received.

The intensity of the program provided challenges for implementation. In particular, the groups were difficult and resource intensive to run. Other studies with pregnant smokers have found difficulties with groups, because some women lack confidence to attend, and transport difficulties and conflicting commitments can prevent attendance.13 Twice-weekly visits early in the program were also difficult to manage, particularly if the AMIHS team was understaffed. A modified version of the program that still provides intensive tailored support is being trialled. This version does not include the groups, provides twice-weekly visits for 2 weeks instead of 3 weeks, and is being provided by a dedicated worker within the antenatal team.

A key element of the program’s success was the sustained, regular support offered, which was critical in maintaining nonsmoking status and encouraging another quit attempt after a relapse. Although the rewards helped motivate women, the key to success was the intensive support that also addressed other social issues women faced and included household members. An intensive smoking cessation program for young, disadvantaged, pregnant Scottish women also found that ongoing support that acknowledged the social context of women’s lives was critical to success.13 This highlights the importance of recognising and addressing the many barriers to smoking cessation faced by women from communities with high smoking prevalence.

The lack of a control group makes it impossible to attribute the high quitting rates to the program. However, the CO-confirmed quit rate in late pregnancy of 42% among all participants and 33% among women smoking at recruitment is considerably higher than the rates in a trial with pregnant Indigenous women in north Queensland, where only 3% of the usual care group and 7% of the intervention group had quit smoking in late pregnancy.6 The confirmed quit rates are also comparable to rates achieved in large trials of CBFR programs.14 Most previous trials of CBFR programs have been efficacy trials run by smoking cessation specialists in academic settings.14 SST is the first CBFR program delivered entirely by existing maternity staff without specialist smoking cessation training.

This small pilot study has several limitations. The lack of a control group and small sample size limit conclusions about its impact. SST was run in three rural sites, and one of these withdrew due to staffing issues, so it may be more challenging to run in different situations. Additionally, women who declined to take part in the program were not interviewed, limiting understanding of their perspectives. Strengths include that quitting was biochemically verified, and that both staff and participants were interviewed.

Conclusion

SST was acceptable and, while some aspects were challenging, it is likely to be feasible to implement with some modifications, and should be tested in a larger study. A revised version of the program is currently being trialled.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a grant from the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. MP was funded by fellowships from the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Cancer Institute NSW and the Sydney Medical Foundation. We wish to thank the AMIHS teams and the women who so graciously participated in this research. Finally, we wish to thank the members of the CRG for their enthusiasm and commitment to this work over 6 years. We absolutely could not have done it without their ongoing support and advice.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, not commissioned

Copyright:

© 2018 Passey and Stirling. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. British Medical Association. Smoking and reproductive life: the impact of smoking on sexual, reproductive and child health. London: BMA; 2004 [cited 2017 Dec 20]. Available from: www.rauchfrei-info.de/fileadmin/main/data/Dokumente/Smoking_ReproductiveLife.pdf

- 2. Chan A, Keane RJ, Robinson JS. The contribution of maternal smoking to preterm birth, small for gestational age and low birthweight among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal births in South Australia. Med J Aust. 2001;174:389–93. PubMed

- 3. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's mothers and babies 2014—in brief. Canberra: AIHW; 2016 [cited 2017 Dec 20]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/australias-mothers-babies-2014-in-brief/contents/table-of-contents

- 4. Thrift AP, Nancarrow H, Bauman AE. Maternal smoking during pregnancy among Aboriginal women in New South Wales is linked to social gradient. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2011;35(4):337–42. CrossRef | PubMed

- 5. Chamberlain C, O'Mara-Eves A, Oliver S, Caird JR, Perlen SM, Eades SJ, Thomas J. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(10):CD001055. CrossRef | PubMed

- 6. Eades SJ, Sanson-Fisher RW, Wenitong M, Panaretto K, D’Este C, Gilligan C, Stewart J. An intensive smoking intervention for pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2012;197(1):42–6. CrossRef | PubMed

- 7. Passey ME, Bryant J, Hall AE, Sanson-Fisher RW. How will we close the gap in smoking rates for pregnant Indigenous women? Med J Aust. 2013;199(1):39–41. CrossRef | PubMed

- 8. National Health and Medical Research Council. Values and ethics: guidelines for ethical conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2003 [cited 2018 Feb 22]. Available from: www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/e52.pdf

- 9. Bryant J, Passey ME, Hall AE, Sanson-Fisher RW. A systematic review of the quality of reporting in published smoking cessation trials for pregnant women: an explanation for the evidence-practice gap? Implement Sci. 2014;9:94. CrossRef | PubMed

- 10. Marteau T, Ashcroft R, Oliver A. Using financial incentives to achieve healthy behaviour. BMJ. 2009;338:b1415. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Volpp KG, Troxel AB, Pauly MV, Glick HA, Puig A, Asch DA, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:699–709. CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. Murphy E, Best E. The Aboriginal Maternal and Infant Health Service: a decade of achievement in the health of women and babies in NSW. NSW Public Health Bull. 2012;23(3–4):68–72. CrossRef | PubMed

- 13. Bryce A, Butler C, Gnich W, Sheehy C, Tappin DM. CATCH: development of a home-based midwifery intervention to support young pregnant smokers to quit. Midwifery. 2009;25(5):473–82. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. Higgins ST, Solomon LJ. Some recent developments on financial incentives for smoking cessation among pregnant and newly postpartum women. Curr Addict Rep. 2016;3:9–18. CrossRef | PubMed