Abstract

Objective: The Australian Government’s landmark 2019 implementation of dedicated Medicare items for people with eating disorders was the first of its kind for a mental illness. We investigate the first 24 months of uptake of these items across regions, settings and healthcare disciplines, including intermediate changes to the program prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: This was a descriptive study using item data extracted from the Australian Medicare Benefits Schedule database for November 2019 to October 2021. Data were cross-tabulated by discipline, setting, consultation type and region.

Results: During the first 24 months of implementation of the scheme, 29 881 Eating Disorder Treatment and Management Plans (or care plans) were initiated, mostly by general practitioners with mental health training. More than 265 000 psychotherapy and dietetic sessions were provided, 29.1% of which took place using telehealth during the pandemic. Although the program offers up to 40 rebated psychological sessions, fewer than 6.5% of individuals completed their 20-session review under the scheme.

Conclusions: Uptake of the Medicare item for eating disorders was swift, and the item was used broadly throughout the pandemic. Although feedback from those with lived experience and experts has been overwhelmingly positive, data show that strategic adjustment may be needed and further evaluation conducted to ensure that the reform achieves the best outcomes for patients and families, and its policy intent.

Full text

Introduction

In November 2019, the Australian Government introduced a set of reforms that drastically altered access to government-rebated private community care options for people with an eating disorder.1 This involved the introduction of Eating Disorder Treatment and Management Plans (EDPs): government–subsidised sessions via the Medicare system for community treatment of eating disorders of 20–60 sessions over approximately the same number of weeks, to better reflect evidence-based therapeutic protocols for this illness group.2-5 This followed a lengthy national consultation process, a year-long advisory group process reporting to the Medicare Benefits Schedule Review Taskforce, and an implementation liaison committee that addressed practical aspects of introducing the initiative. Previously, access to mental health services for any person with a mental health condition was provided via the Better Access (to mental health) scheme6, introduced in 2001. This scheme covered up to 10 rebated psychological sessions per year.

The new EDP scheme means that people with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and other specified feeding and eating disorders who meet the criteria have access to up to 40 rebated sessions of psychological therapy per year, along with 20 dietetic sessions. Regular appointments with a general practitioner/family physician (GP) every 10 sessions were also built into the architecture of the system, and consultation with a psychiatrist and/or paediatrician was mandated at the mid-point of care (20 psychological sessions) to confirm diagnosis and the ongoing need for treatment.7

In March 2020, in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the Australian Government introduced the first telehealth delivery items for rebated mental health care services under the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) for people outside remote geographic regions.8 As a result of this change in the ability to deliver services using telehealth and the national lockdowns that occurred in every Australian state and territory around that time, uptake of telehealth services for mental health conditions increased greatly.9 Evidence suggests that it has not decreased to pre-pandemic levels.10,11

Eating disorders are serious mental and physical illnesses that have among the highest mortality rates of all mental illnesses and carry significant economic cost to the community12-14 Yet, if treated early with an evidence-based package, full remission is often realised15,16, the individual returns to a normal developmental trajectory, and the burden on the health system is reduced. Access to an adequate dose of therapeutic care is therefore needed within the community. This was reflected by the MBS revisions, allowing rebated access to this level of care. The EDP scheme targets moderate to severe illness, with specific eligibility criteria of a clinical diagnosis plus a score above the clinical cut-off on an evidence-based symptom severity measure – excepting those with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa who, because of the severity of the diagnostic category, have the latter requirement waived.17,18

This set of reforms to the MBS makes eating disorders the first diagnostic category among mental illnesses to have its own item numbers. That mental illnesses have been grouped together until now has been a major impediment to attempts to examine the efficacy of the MBS Better Access scheme for specific mental health disorders. The current report is therefore the first to examine the use of Medicare-rebated services in treatment of eating disorders.

The aim of the current study was to broadly examine the national response to the scheme post-implementation, to understand whether the intent of the policy is being met. We report on the rate of uptake of the new eating disorder item numbers across Australia, identify health professionals by type of service they provided and by setting (face-to-face or telehealth), and examine patterns of use across states and territories. We were not able to address people with eating disorders treated under the Better Access scheme because of the lack of any diagnostic category in that program; nor could we account for people who claimed psychological sessions under Better Access rather than under an EDP.

Methods

We performed descriptive analysis of all new Medicare item numbers introduced as part of the EDP scheme from 1 November 2019 to 31 October 2021. Data included all GP, specialist medical, mental health and dietetic services with an item number for eating disorders introduced in November 2019. Providers were GPs, psychiatrists, paediatricians, clinical psychologists and other eligible providers of psychological services, and registered dietitians.

Service use was ascertained from the MBS. The MBS provides a list of all government-subsidised out-of-hospital healthcare services. Data on service use are publicly available19 and provide monthly counts of services by service category. Relevant service categories in this analysis were initiation of treatment and management plans for eating disorders, review of treatment and management plans for eating disorders, and dietetic services or psychological services billed against the scheme. Relevant MBS item categories were classified into face-to-face and telehealth services, and stratified by practitioner type and state/territory. For service setting, ‘COVID video/phone’ is distinct from ‘video remote’; the latter was an existing item reserved for those living more than 15 km from services, and the former was introduced nationwide in March 2020 during the pandemic to ensure access to services via telehealth during the crisis.

Main outcome measures were service use rates.

Data were analysed using simple descriptive statistics for total number of consultations cross-tabulated to express frequencies and distributions across discipline, setting, duration and region. Frequency of service uptake was calculated to provide proportional uptake of some key services by state and territory (i.e. number of services delivered divided by total state or territory population).

Results

Eating Disorder Treatment and Management Plans (EDP) and reviews

A total of 29 881 EDPs (also referred to as eating disorder care plans) were initiated from November 2019 to October 2021, mostly by GPs (93.4%), 77.5% of whom have mental health training and 22.5% of whom do not (Table 1). The remainder were provided by psychiatrists (3.6%), paediatricians and ‘other medical practitioners’ (less than 1.5% each). However, in contrast to the other states, psychiatrists provided more than 20% of EDPs in South Australia.

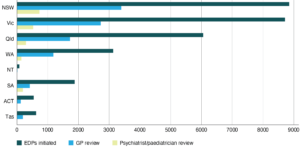

The majority of EDPs were provided in rooms (face-to-face) (82.4%), and 12.0% were provided as a COVID telephone service. Only 5.3% were provided as a COVID video service. Distribution of EDPs provided by state and territory was relative to population. The majority were delivered in New South Wales (29.6%), followed by Victoria (29.2%) and Queensland (20.3%) (see Figure 1). In most states and territories, this equated to 0.11–0.13% of the state or territory population, except in the Northern Territory, where only 0.03% of the population were provided with an EDP.

Figure 1. Eating disorder care plans initiated and reviewed, by Australian state and territory, November 2019 – October 2021 (click on figure to enlarge)

Table 1. Eating disorder care plans initiated and reviewed by discipline, Australia, November 2019 – October 2021

| Discipline | Initiated | Reviewed | ||||||

| Setting | Duration | |||||||

| In rooms N (%) |

Video remotea N (%) |

COVID video N (%) |

COVID phone N (%) |

Total N (%) |

Shortb N (%) |

Longc N (%) |

||

| GP | 23 016 (82.5) |

NA | 1 451 (5.2) |

3 431 (12.3) |

27 898 (93.4) | 14 865 (53.3) | 13 033 (46.7) |

9780 (82.7) |

| Psychiatrist | 859 (80.2) |

72 (6.7) |

91 (8.5) |

48 (4.5) |

1 070 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) |

1 070 (100.0) |

1596 (13.5) |

| Paediatrician | 369 (87.2) |

16 (3.8) |

34 (8.0) |

4 (0.9) |

423 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

423 (100.0) |

334 (2.8) |

| Other medical practitioner | 376 (76.7) |

NA | 16 (3.3) |

98 (20.0) |

490 (1.4) | 242 (49.4) |

248 (50.6) |

116 (1.0) |

| Total | 24 620 (82.4) |

88 (0.3) |

1 592 (5.3) | 3 581 (12.0) |

29 881 (100.0) |

15 107 (50.6) |

14 77, (50.4) | 11 826 (100.0) |

NA = not applicable

a Video remote’ means non-COVID video items. These items are for patients located within a telehealth-eligible area – that is, at the time of attendance located at least 15 km by road from the treating professional.

b ‘Short’ means <40 minutes (GP, other medical practitioner) or <45 minutes (psychiatrist, paediatrician).

c ‘Long’ means >40 minutes (GP, other medical practitioner) or >45 minutes (psychiatrist, paediatrician).

Just under half (49.3%) of the consultations provided to initiate an EDP were of ‘long’ duration – that is, longer than 40 minutes in the case of GPs and other medical practitioners, or 45 minutes in the case of psychiatrists and paediatricians.

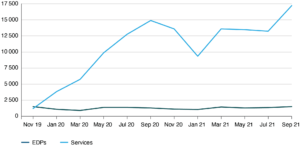

The distribution by month of initiation of EDPs is shown in Figure 2. The largest number of EDPs were processed in August 2021, at the height of extended COVID lockdowns across the country; however, distribution was fairly stable across the 24 months.

Of people with an EDP, a maximum of 26.3% reached a review; a total of 11 826 reviews were provided under an EDP in the 24-month period. A maximum of 6.5% completed a 20-session review, which gives access to an additional 20 rebated psychological sessions (to a total of 40). Reviews were mostly assessed by GPs (82.7%) with 23.4% undertaken via COVID telehealth. Psychiatrists and paediatricians, who must conduct the 20-session review, undertook a combined 16.3% of all reviews.

Figure 2. Eating disorder care plans and services initiated by month, Australia, November 2019–October 2021 (click on figure to enlarge)

Services

A total of 266 056 eating disorder treatment services were delivered in the 24-month period, (Table 2). These comprised 189 832 psychological and 76 224 dietetic services. Two-thirds (65.1%) of all services were delivered face-to-face in rooms and 25.8% as a COVID video service. The remaining services were provided as video remote (where an eligible patient lives more than 15 km from the treating professional), COVID telephone and ‘out-of-rooms’ services. An average of 8.9 services were provided per EDP (6.3 psychotherapy sessions and 2.6 dietetic sessions).

Table 2. MBS eating disorder services provided by discipline, Australia, November 2019 – October 2021

| Discipline | Services provided | Duration of consultation | Location of consultation | ||||||

| Psychology N (%) |

Dieteticsa N (%) |

Shortb N (%) |

Longc N (%) |

In rooms N (%) |

Out of rooms N (%) |

Video remoted N (%) |

COVID video N (%) |

COVID phone N (%) |

|

| Psychologist (clinical) | 114 763 (60.5) |

NA | 1 329 (1.2) |

113 434 (98.8) |

74 965 (67.3) |

720 (0.6) | 6 420 (4.6) |

29 022 (24.1) |

3 636 (3.4) |

| Psychologist (registered) | 64 591 (34.0) |

NA | 1 179 (1.8) |

63 412 (98.2) |

42 444 (66.2) |

599 (1.2) | 3 385 (4.7) |

16 889 (25.5) |

1 274 (2.4) |

| Social worker | 8 767 (4.6) |

NA | 316 (3.6) |

8 451 (96.4) |

5 829 (65.3) |

641 (6.5) | 706 (6.4) |

1 363 (19.1) |

228 (2.7) |

| Occupational therapist | 711 (0.4) |

NA | 40 (5.6) |

671 (94.4) |

573 (79.7) |

24 (2.5) |

27 (0.3) |

83 (16.3) |

4 (1.2) |

| GP | 897 (0.5) |

NA | 102 (11.4) |

795 (88.6) |

398 (23.8) |

0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

50 (3.4) |

449 (72.9) |

| Other medical practitioner | 103 (0.05) |

NA | 5 (4.8) |

98 (95.2) |

15 (23.4) |

0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 75 (56.2) |

13 (20.3) |

| Dietitian | NA | 76 224 (100.0) | NA | NA | 49 070 (64.4) |

0 (0.0) | 2 723 (3.1) |

21 270 (27.7) |

3 161 (4.7) |

| Total | 189 832 (100.0) |

76 224 (100.0) |

2 971 (1.1)* |

186 861 (70.2)* |

173 294 (65.1)* |

1 984 (0.7)* |

13 261 (5.0)* |

68 752 (25.8)* |

8 765 (3.3)* |

NA = not applicable

a All dietetic sessions were >20 minutes.

b Short’ means <30–50 minutes (clinical psychologist), 20–50 minutes (registered psychologist, occupational therapist, social worker) or 30–40 minutes (GP, other medical practitioner).

c ‘Long’ means >40 minutes (GP, other medical practitioner) or >50 minutes (clinical psychologist, registered psychologist, occupational therapist, social worker).

d Video remote’ means non-COVID video items. These items are for patients located within a telehealth-eligible area – that is, at the time of attendance located at least 15 km by road from the treating professional.

* Percentages are based on total services provided (including both psychology and dietetics services)

The monthly frequency of services provided increased between November 2019 and September 2020 – from 1207 sessions in November 2019 to 14 917 sessions in September 2020 – before declining to around 9000–11 000 per month from late 2020. Service provision steadily increased again from May 2021 to a peak of 17 246 in September 2021.

Psychological services

A total of 189 832 psychotherapy sessions were provided under EDPs over the 24-month period. These were mostly delivered by clinical psychologists (60.5%) and registered psychologists (34.0%). More than 98% of the sessions were of ‘long’ duration (more than 50 minutes for psychologists and allied health, and more than 40 minutes for GPs). They were delivered mostly in New South Wales (NSW) (33.4%), followed by Victoria (29.1%) and Queensland (18.2%). This was proportionate to population in every state and territory except the Northern Territory (0.2%). More than 33% of all psychotherapy sessions were provided using telehealth services; one-quarter (28.0%) of these were COVID services, and 5.5% were regular telehealth services delivered to individuals in regional and remote locations.

Dietetic services

A total of 76 224 dietetic services were provided under EDPs over the 24-month period. All were longer than 20 minutes in duration. The largest proportion were provided in Victoria (31.5%), followed by NSW (28.5%) and Queensland (23.0%). Again, relative to population, the rate of access was similar across all states and territories except the Northern Territory (0.10%). Of the dietetic sessions, 32% were provided as a COVID telehealth service.

Uptake of COVID telehealth services

Provision of COVID telehealth services implemented in March 2020 was significant. Just over 17% of EDPs processed and 29.1% of all eating disorder treatment services provided used a COVID telehealth service/item number. There was a peak of service provision at the height of regional lockdowns. Almost half (48.0%) of all COVID telehealth services were provided in Victoria, the state most affected by regional lockdowns during the pandemic; 33.7% were delivered in NSW and 10.7% in Queensland.

Discussion

Almost 29 881 EDPs were initiated in the 24-month period from the implementation of the scheme, which equates to approximately 0.12% of the Australian population accessing a plan. Considerably more plans were initiated than reviewed in the first 24 months of operation of the scheme across all states and territories, indicating that many people are not claiming the full number of psychological sessions they are entitled to under the scheme; most did not move beyond the first review at the 10-session mark. Although the data did not allow determination of the number of sessions delivered per client, we calculated an average of nine services per EDP, the majority being psychological sessions (approximately six psychological services and two dietetic sessions per individual). The same pattern was observed across the dataset, with dietetic services claimed accounting for less than one-third of the total number of services. This is to be expected because most treatment models for eating disorders involve weekly psychological therapy sessions, with less frequent dietetic input.20

Under the MBS, psychological services can be delivered by a range of mental health professionals. Data from the first 24 months of operation of the EDP scheme reveal that the vast majority of these services were provided by clinical psychologists, followed by registered psychologists, and very few were provided by other mental health care providers. This could in part reflect the different rebates for mental health professionals – clinical psychologists receive the highest rebates and hence have sufficient motivation for delivering these services. Alternatively, it could be because the available evidence-based treatments for most eating disorders are mainly developed by clinical psychologists, who tend to be the group most often trained in them.

Most people given an EDP are provided with the plan by their GP; the majority (77.5%) of these were specialist mental health trained. Since only a portion of the GP workforce is specialist mental health trained, this may have access implications for people with eating disorders who present to GPs who are not mental health trained, as well as for the mental health trained portion of the GP workforce who, in this study, provide the majority of access and care planning under this scheme. The only variation to this pattern was found in South Australia where, although GPs still initiated most care plans, psychiatrist-initiated plans accounted for a larger proportion than in other states and territories (approximately 20% vs 0–4.90%).

GPs can conduct a 10-session review; they are required to conduct a review at 20 and 30 sessions alongside a psychiatrist or paediatrician. It is not possible to distinguish between the three levels of review claimable under the one item number. However, given that only 16.3% of all EDPs reviewed were psychiatry or paediatrician reviews (1970 in total), and these reviews must occur at the 20+ session mark, at least 75% of people are not moving past the 10-session review, and very few access care under the scheme beyond 20 sessions of therapy. Although there is some evidence that milder eating disorders can be treated in less than 10 sessions21,22, and a body of literature suggests that a range of eating disorders can be treated within 20 sessions, most research suggests that the more severe eating disorders require 40 or more psychological sessions to achieve remission.5 Because the policy intent of the reform was to provide care for moderate and severe illness23, these early data suggest that the scheme in its current configuration is not achieving this aim. This may be because of several factors, including financial burden (despite the rebate, individuals usually make a gap payment that can be significant), accessibility issues (many clinicians have long waiting lists, and a limited number are eating disorder trained)24, the limited number of specialist psychiatrists for review in most locations, confusion about the process to access services beyond the 10- and 20-session marks both on the client side and for the GP, and lack of treatment efficacy and/or patient engagement. Further research should be undertaken to explore potential barriers to effective implementation of a scheme specifically designed to extend access to services where access was previously insufficient.

Low overall use of psychiatrists within the scheme may reflect the higher gap payment charged by this professional group and/or limited availability of psychiatrists with expertise in eating disorders. If the latter, an urgent need exists to develop the specialty workforce and train psychiatric physicians in eating disorder management. Further investigations are suggested to determine whether the current configuration of the scheme is suited to the practice habits of the psychiatry profession – specifically, whether psychiatrists are reluctant to engage a new patient only for the purposes of providing them with an EDP or review.

The introduction of social restrictions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in March 202025 saw both a spike in the overall number of EDPs initiated – to almost the same levels as at the advent of the scheme – and the introduction of COVID telehealth items. Just over 17% of all EDPs were initiated in the period using a COVID telephone or video service item, and 25.8% of all psychological and dietetic services provided used a COVID video service item number, with very few using telephone. Unsurprisingly, given that it had the harshest and longest lockdowns of any state or territory, the largest proportion of telehealth/video item numbers were claimed in Victoria, highlighting the importance of government support for this pathway to access care for many Australians during the past 2 years.

The rates of access to EDPs and services mostly aligned with the population in each state and territory, except for the Northern Territory, where the rate of EDPs and services claimed was much lower. This may reflect the state’s largely rural and remote population, and the resultant difficulties accessing mental health clinicians26-28, or an underdeveloped workforce with limited capability to treat eating disorders.29 Further, the Northern Territory has a large Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population (25% compared with 3.4% in New South Wales) who, despite being more vulnerable to eating disorders, are less likely to seek help.30 Further research must be undertaken, and policy designed, to understand and address potential inequities in service access.

The present data are limited by the inability to ascertain service contact per individual client, meaning that individual patterns of use and detailed inferential statistics were beyond the scope of the study. The study must therefore be regarded as indicative; detailed individual-level data evaluation of the program is needed. Additionally, data reflecting the proportion of the health workforce trained in mental health and specifically eating disorders are scant. The number of services delivered to people with eating disorders in this report is an underestimate because services for people with eating disorders treated under the MBS Better Access scheme cannot be analysed. EDPs are only for individuals with moderate to severe eating disorders, and those with milder illness treated under Better Access are not reported here. Further, there are many anecdotal reports of individuals with moderate to severe eating disorders first accessing the 10 psychological sessions rebated under Better Access and then progressing to an EDP, and reports of psychological service providers inadvertently billing Better Access rather than an EDP (which is allowed under the scheme).

Conclusion

The change to the MBS to give people with eating disorders access to the number of sessions recommended by the evidence was an important step forward in evidence-based care provision. Although feedback on the introduction of this reform to the MBS from people with lived experience of an eating disorder and experts in the field has been overwhelmingly positive, this study suggests that the program may need some adjustments to ensure that the policy intent is achieved. A full evaluation of individual service use data is warranted to provide a full and accurate picture of program uptake and use, and better identify barriers to implementation. Improving access for targeted populations and access to professional groups trained in eating disorders, improving service retention and undertaking further research into the best models for policy context would ensure that this landmark reform for an illness group with relatively low remission and high mortality rates achieves its intent and has the greatest impact on remission rates, personal suffering and health system burden.

† MAINSTREAM Research Collective (consortium authorship) includes:

Prof Stephen Touyz, Ms Danielle Maloney, Dr Jane Miskovic-Wheatley, Phillip Aouad, Dr Sarah Maguire, the InsideOut Institute for Eating Disorders, Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney; Prof Ian Hickie from the Brain and Mind Centre, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney; Prof Janice Russell, Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney; Dr Sloane Madden, School of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney; Dr Warren Ward, School of Medicine, University of Queensland; Dr Michelle Cunich, Boden Institute, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Prof Natasha Nassar, Child Population and Translational Health Research, Children’s Hospital at Westmead Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney; and Ms Claire Diffey, Centre for Excellence in Eating Disorders, Victoria.

Acknowledgements

Authors NN and SM were funded by an NHMRC grant from the Medical Research Future Fund Mainstream Centre for Health System Research and Eating Disorders.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, not commissioned.

Copyright:

© 2022 Maguire et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Australian Government. Upcoming changes to MBS items – eating disorders. Australian Government Department of Health; 2019 [cited 2021 May 17]. Available from: www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/Factsheet-EatingDisorders

- 2. Le Grange D. The Maudsley family-based treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa. World Psychiatry. 2005;4(3):142–6. PubMed

- 3. McIntosh VVW, Jordan J, Luty SE, Carter FA, McKenzie JM, Bulik CM, et al. Specialist supportive clinical management for anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(8):625–32. CrossRef | PubMed

- 4. Fairburn CG, Bailey-Straebler S, Basden S, Doll HA, Jones R, Murphy R, et al. A transdiagnostic comparison of enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-E) and interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders. Behav Res Ther. 2015;70:64-71. CrossRef | PubMed

- 5. Zipfel S, Giel KE, Bulik CM, Hay P, Schmidt U. Anorexia nervosa: aetiology, assessment, and treatment. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;1;2(12):1099–111. CrossRef | PubMed

- 6. Australian Government. Better Access initiative. Australian Government Department of Health; 2020 [cited 2021 May 17]. Available from: www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/better-access-initiative

- 7. Australian Government. Eating disorders quick reference guide. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health; 2019 [cited 2022 Jun 16]. Available from: www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/773AA9AA09E7CA00CA2584840080F113/$File/Eating%20Disorders%20Quick%20Reference%20Guide%2029Oct2019.pdf

- 8. Australian Government. MBS changes factsheet COVID-19 Temporary MBS Telehealth Services. 2020. Available from: www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/0C514FB8C9FBBEC7CA25852E00223AFE/$File/Factsheet-COVID-19-GPsOMP-Post-1July2021V5.pdf

- 9. Jayawardana D, Gannon B. Use of telehealth mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aust Health Rev. 2021;45(4):442–6. CrossRef | PubMed

- 10. Looi JC, Allison S, Bastiampillai T, Pring W, Reay R. Australian private practice metropolitan telepsychiatry during the COVID-19 pandemic: analysis of Quarter-2, 2020 usage of new MBS-telehealth item psychiatrist services. Australas Psychiatry. 2021;1;29(2):183–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Looi JC, Allison S, Bastiampillai T, Pring W, Reay R, Kisely SR. Increased Australian outpatient private practice psychiatric care during the COVID-19 pandemic: usage of new MBS-telehealth item and face-to-face psychiatrist office-based services in Quarter 3, 2020. Australas Psychiatry. 2021;1;29(2):194–9. CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. The Butterfly Foundation. Paying the price: the economic and social impact of eating disorders in Australia. Sydney: The Butterfly Foundation; 2012 [cited 2020 Oct 16]. Available from: Available from: butterfly.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Butterfly_Report_Paying-the-Price.pdf

- 13. Streatfeild J, Hickson J, Austin SB, Hutcheson R, Kandel JS, Lampert JG, et al. Social and economic cost of eating disorders in the United States: evidence to inform policy action. Int J Eat Disord. 2021;54(5):851–68. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. Tannous WK, Hay P, Girosi F, Heriseanu AI, Ahmed MU, Touyz S. The economic cost of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: a population-based study. Psychol Med. 2021;17:1–15. CrossRef | PubMed

- 15. Loeb KL, le Grange D. Family-based treatment for adolescent eating disorders: current status, new applications and future directions. Int J Child Adoleschealth. 2009;1;2(2):243–54. PubMed

- 16. Austin A, Flynn M, Richards K, Hodsoll J, Duarte TA, Robinson P, et al. Duration of untreated eating disorder and relationship to outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2021;29(3):329–45. CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. Birmingham CL, Su J, Hlynsky JA, Goldner EM, Gao M. The mortality rate from anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38(2):143–6. CrossRef | PubMed

- 18. Wonderlich SA, Bulik CM, Schmidt U, Steiger H, Hoek HW. Severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: update and observations about the current clinical reality. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(8):1303–12. CrossRef | PubMed

- 19. Medicare Australia. Services Australia – statistics – Medicare item reports. 2022 [cited 2022 Jul 12]. Available from: medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.jsp

- 20. McMaster CM, Wade T, Franklin J, Hart S. Development of consensus-based guidelines for outpatient dietetic treatment of eating disorders: a Delphi study. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(9):1480–95. CrossRef | PubMed

- 21. Waller G, Tatham M, Turner H, Mountford VA, Bennetts A, Bramwell K, et al. A 10-session cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT-T) for eating disorders: outcomes from a case series of nonunderweight adult patients. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51(3):262–9. CrossRef | PubMed

- 22. Barakat S, Maguire S, Surgenor L, Donnelly B, Miceska B, Fromholtz K, et al. The role of regular eating and self-monitoring in the treatment of bulimia nervosa: a pilot study of an online guided self-help CBT program. Behav Sci (Basel). 2017;7(3):39. CrossRef | PubMed

- 23. Australian Government. Medicare benefits schedule – Item 90250. Australian Government Department of Health. [cited 2021 Jun 4]. Available from: www9.health.gov.au/mbs/fullDisplay.cfm?type=item&qt=ItemID&q=90250

- 24. Worsfold KA, Sheffield JK. Eating disorder mental health literacy: what do psychologists, naturopaths, and fitness instructors know? Eat Disord. 2018;26(3):229–47. CrossRef | PubMed

- 25. Chang SL, Harding N, Zachreson C, Cliff OM, Prokopenko M. Modelling transmission and control of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5710. CrossRef | PubMed

- 26. Hunter E. Disadvantage and discontent: a review of issues relevant to the mental health of rural and remote Indigenous Australians. Aust J Rural Health. 2007;15(2):88–93. CrossRef | PubMed

- 27. Sheridan T, Brown LJ, Moy S, Harris D. Health outcomes of eating disorder clients in a rural setting. Aust J Rural Health. 2013;21(4):232–3. CrossRef | PubMed

- 28. Weber M, Davis K. Food for thought: enabling and constraining factors for effective rural eating disorder service delivery. Aust J Rural Health. 2012;20(4):208–12. CrossRef | PubMed

- 29. Eating Disorders Training Australia. Eating disorders training Australia. 2022 [cited 2022 Jul 11]. Available from: www.nedc.com.au/assets/Uploads/NEDC-Report-Eating-Disorders-Training-in-Australia-Dec-2018.pdf

- 30. Burt A, Mannan H, Touyz S, Hay P. Prevalence of DSM-5 diagnostic threshold eating disorders and features amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander peoples (First Australians). BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):449. CrossRef | PubMed