Abstract

The history of unethical and inhumane research conducted on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people since colonisation highlights the critical need for specific Human Research Ethics for research involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. The development of Aboriginal Human Research Ethics Committees (AHRECs) has played a vital role in ensuring research is safe and delivered for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in a way that protects and promotes their health and wellbeing. However, there remains a lack of appropriate and critical ethical governance for such research in areas without specific Aboriginal HRECs in each jurisdiction. This perspective argues that greater investment in state-based AHRECs and consideration of a national AHREC are essential to ensure the ongoing health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the research process –the ultimate aim of any research that involves them.

Full text

Background

Standards for ethical conduct in research practice and governance of ethical review have been operationalised in medical research in Australia since the 1960s to protect the health and wellbeing of research participants.1 Alongside these guidelines, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have driven the prioritisation, establishment, and governance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-specific Human Research Ethics.2-4 The critical need for this ethical regulation was driven by the legacy of unethical and inhumane research conducted on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people since colonisation.5-7 This was, and still is, causing harm.8

Despite the well-documented need for and development of HRECs3,9-11, we, as Aboriginal researchers (MK, SMF and MD) and co-chairs of the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW (SMF and MD), know that more needs to be done in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research ethics space to ensure the wellbeing of research participants. Many researchers do not apply the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander guidelines appropriately.12,13 It is unclear if this results from a lack of education and knowledge of the guidelines, researchers’ competing demands and time limitations, a lack of understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and histories2 or, at worst, blatant disregard for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s specific values and principles for research to ensure no further harm is caused due to research practice. The previous and ongoing issues gave rise to the development of Aboriginal Human Research Ethics Committees, which play a vital role in ensuring research is safe and delivered for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in a way that protects and promotes their health and wellbeing.

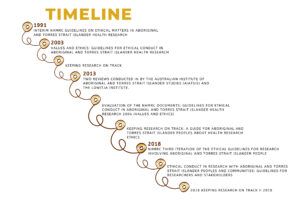

The first Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander guidelines were published in 199114, with the most recent version published in 20188 by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). There have also been several reviews of the guidelines to ensure they reflect today’s standards (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Timeline of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Human Research Ethics Guidelines in Australia 2,9,15-17 (click on figure to enlarge)

Aboriginal health research guidelines

The NHMRC, a statutory body responsible for managing investment in and the integrity of health and medical research18, has developed these guidelines with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. They are referred to in the National Statement of Ethical Conduct in Human Research (National Statement), which requires studies involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people must consult the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander guidelines when designing research.19

While ethical guidelines for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research have been implemented for decades, the governance of ethical review continues to have limitations and challenges for researchers and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. There are currently two types of ethical governance: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Human Research Ethics Committees (AHRECs) (see Figure 2)20-22 under the auspices of Jurisdictional Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (ACCHOs) and one Aboriginal sub-committee in the Northern Territory under the auspices of the Menzies School of Health Research.23 Jurisdictional ACCHOs, otherwise known as Jurisdictional Peak Bodies or National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation Jurisdictional Affiliates, are Aboriginal organisations that are member-based organisations run by and for the Aboriginal people. Their members are ACCHOs from within their jurisdiction. Their governance structure ensures Aboriginal self-determination with Boards consisting of Aboriginal people who represent their members.24 Their primary function is policy, advocacy and programs to support their members’ comprehensive primary health care service delivery.25

Figure 2. Aboriginal Human Research Ethics Committees in Australia by state 20-22(click on figure to enlarge)

AHREC = Aboriginal Human Research Ethics Committee; AH&MRC = Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council NSW Ethics Committee; WAHREC = Western Australian Aboriginal Human Research Ethics Committee.

The Northern Territory Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) sub-committee is not included in this image because it is not Aboriginal community controlled; therefore, it is not an AHREC.

The essential role of AHRECs

The AHRECs require researchers to detail how the health and wellbeing research that impacts Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is conducted in a culturally safe way and is of maximum benefit to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. It is worth noting that researchers self-report the mechanisms to ensure cultural safety. The AHRECs ensure appropriate levels of community engagement throughout research projects and, wherever possible, that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are the research leads. Chaired by Aboriginal people, with a majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on the HREC committees20-22, AHRECs are best placed to interpret and apply the National Statement and the relevant guidelines from an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspective. This is because, for other types of AHRECs, the implementation of the NHMRC Guidelines varies significantly.12

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-specific ethics has a long and proud history in Australia. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have the right to participate in and lead research to improve their health and wellbeing. The appropriate governance of ethical review and research monitoring is critical to implementing respectful and ethical research practices and the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. However, where there is no Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander HREC (Victoria, Queensland, Australian Capital Territory and Tasmania), there is a lack of appropriate and critical ethical governance. Consideration should also be given to funding an AHREC in the Northern Territory, as the current HREC sub-committee is not community controlled.

AHRECs are essential to ensure the ongoing health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the research process – the ultimate goal of research involving them.

A call for national action

We, therefore, call for increased investment in the current state-based HRECS and established Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-specific HRECs within the remaining community-controlled peak bodies. We firmly believe that AHRECs are best placed to ensure that research projects are positioned to be conducted in a culturally safe way that benefits Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Additionally, given that much research is national or multijurisdictional, there is merit in exploring the establishment of a national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander HREC. What this would look like, how it would engage with the jurisdictional AHRECs and who would fund it would need to be addressed. These issues are not insurmountable, given the potential benefits to AHRECs, researchers and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

AHRECs are essential to ensure the ongoing health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the research process – which is the ultimate goal of research that involves Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Acknowledgements

SMF and MD are Co-Chairs of the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC). MK is a Board member and Associate Editor, Indigenous Health with PHRP. She had no involvement in the review or decisions on this manuscript.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, invited.

Copyright:

© 2023 Finlay et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Dodds S, Ankeny RA, editors. Big picture bioethics: developing democratic policy in contested domains. Springer International Publishing; 2016. CrossRef

- 2. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AU), Lowitja Institute (AU). Researching right way. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research ethics: a domestic and international review. Australia: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Lowitja Institute; 2013 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: www.nhmrc.gov.au/file/3561/download?token=w4Nxp1_M

- 3. National Health and Medical Research Council (AU). Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and communities: guidelines for researchers and stakeholders. Canberra: NHMRC; 2018 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/resources/ethical-conduct-research-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples-and-communities

- 4. Lowitja Institute. Ethics hub. Collingwood: Lowitja Institute; 2022 [cited 2022 Dec 20]. Available from: www.lowitja.org.au/page/research/ethic-hub

- 5. Cunningham DJ. The spinal curvature in an Aboriginal Australian. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 1889 Dec 31;45(273–279):487–504. CrossRef

- 6. Vivian A, Halloran MJ. Dynamics of the policy environment and trauma in relations between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the settler-colonial state. Critical Social Policy. 2022 Nov;42(4):626–47. CrossRef

- 7. Lewis D. Australian biobank repatriates hundreds of ‘legacy’ Indigenous blood samples. Nature. 2020;577(7788):11–12. CrossRef | PubMed

- 8. Gillam L, Pyett P. A commentary on the NH&MRC Draft values and ethics in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Monash Bioeth Rev. 2003;22(4):8–19. CrossRef | PubMed

- 9. National Health and Medical Research Council. Values and ethics: guidelines for ethical conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2003 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/values-and-ethics-guidelines-ethical-conduct-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-health-research

- 10. Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council of New South Wales. AH&MRC ethical guidelines: key principles (2020) V2.0. Sydney: AH&MRC; 2020 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: www.ahmrc.org.au/publication/ahmrc-guidelines-for-research-into-aboriginal-health-2020

- 11. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. AIATSIS code of ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research. Canberra: AIATSIS; 2020 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/aiatsis-code-ethics.pdf

- 12. Burchill LJ, Kotevski A, Duke DL, Ward JE, Prictor M, Lamb KE, et al. Ethics guidelines use and Indigenous governance and participation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research: a national survey. Med J Aust. 2023;218(2):89–93. CrossRef | PubMed

- 13. McGuffog R, Chamberlain C, Hughes J, Kong K, Wenitong M, Bryant J, et al. Murru Minya – informing the development of practical recommendations to support ethical conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research: a protocol for a national mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(2):e067054. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. Humphery K. Setting the rules: the development of the NHMRC guidelines on ethical matters in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. N Z Bioeth J. 2003 Feb;4(1):14–9. PubMed

- 15. National Health and Medical Research Council (AU). Keeping research on track: a guide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples about health research ethics. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2005 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/keeping-research-track

- 16. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Lowitja Institute (AU). Evaluation of the National Health and Medical Research Council documents: guidelines for ethical conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research 2004 (Values and ethics) and keeping research on track: a guide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples about health research ethics in 2005 (Keeping research on track). Canberra: AIASIS, Lowitja Institute; 2013 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/reports/evaluation-ethical-conduct-on-track.pdf

- 17. National Health and Medical Research Council (AU). Keeping research on track II: a companion document to ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities: guidelines for researchers and stakeholders. NHMRC: Canberra; 2018 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/resources/keeping-research-track-ii

- 18. National Health and Medical Research Council (AU). The statement of expectations outlines the expectations of the government for NHMRC's role, responsibilities and relationship with the government. Canberra: NHMRC; 2020 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: Available from: www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/who-we-are/statement-expectations

- 19. National Health and Medical Research Council (AU), Australian Research Council (AU), and Universities Australia (AU). National statement on ethical conduct in human research 2007 (updated 2018). Canberra: NHMRC; 2018 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/national-statement-ethical-conduct-human-research-2007-updated-2018

- 20. Aboriginal Health Council of Western Australia (AU). Western Australian Aboriginal human ethics committee. Aboriginal Health Council of Western Australia; 2022 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: www.ahcwa.org.au/sector-support/waahec/

- 21. Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW (AU). Ethics at AH&MRC. Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW; 2019 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: www.ahmrc.org.au/ethics-at-ahmrc

- 22. Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia (AU). Aboriginal health research ethics committee. Adelaide: Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia; 2022 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: ahcsa.org.au/research-and-ethics/ethical-review-ahrec

- 23. NT Health Library Services. Research impact: human research ethics committee. Darwin: Northern Territory Government; 2022 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: library.health.nt.gov.au/ResearchImpact/hrec

- 24. Finlay SM. Understanding the impacts of the national key performance indicators on Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations. Adelaide: University of South Australia; 2020.

- 25. National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO). NACCHO Affiliates. Canberra: NACCHO; 2022 [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: www.naccho.org.au/naccho-affiliates/