Abstract

Objectives: To trial methods for a future longitudinal study to: a) assess how the redevelopment of a large social housing estate affects the health of tenants; and b) act on health needs identified throughout the redevelopment.

Type of program or service: Self-reported health assessment with referral to community-based link worker.

Methods: Participants recruited from the tenant population completed (online or face-to-face) a health questionnaire covering self-reported health status and behaviours, housing conditions, sense of community, and demographics. Those identified as being at moderate/high risk of psychological distress and/or alcohol use disorder were contacted by a community-based link worker, who connected them with health/human services as appropriate.

Results: A total of 24 tenants were recruited for the pilot study against a target sample size of 50. The health questionnaire and referral process worked as expected, with no issues reported.

Lessons learnt: This pilot study successfully trialled methods for: a) assessing tenants’ health; and b) referring those identified as being likely to have unmet health service needs to a community-based link worker, leveraging existing collaborations between academics, the local health district and community groups.

Fewer tenants than expected, and none aged younger than 35 years, participated in the survey. Furthermore, the substantial number of suspicious/fraudulent responses was not anticipated. Recruitment and data collection approaches must be reviewed to address these issues if this study is to be scaled up.

Although only a pilot project, we connected several tenants who had unmet health needs with a health service. While it is impossible to generalise from our small sample, the number of referrals (one-quarter of participants) indicates a potentially large unmet need for health services in the community. It highlights the importance of link workers or other person-centred integrated care interventions in social housing populations.

Full text

Introduction

Housing is an important determinant of health. While Australia has the highest median household wealth in the world1, 10% of adults live in dwellings likely to harm their physical or mental health, and public housing tenants are more likely than homeowners to live in unhealthy housing.2

Australia had approximately 440 200 social housing dwellings in 2021, of which 68% were public housing (state or territory-owned and managed), 25% were community housing (managed by community housing organisations [CHOs]), and the remainder were Indigenous housing.3 Many of these dwellings are ageing and have issues with damp/mould and thermal comfort.4 The New South Wales (NSW) Government’s Communities Plus program aims to redevelop some public housing estates to have a higher density and a mix of 70% private and 30% community housing5; however, there is little policy focus on the impacts of this program on tenants’ health.

One planned Communities Plus project is the redevelopment of the Waterloo estate in inner-city Sydney, requiring approximately 2000 households to be rehoused. Many of the tenants have complex health needs and high health service utilisation.6 This is partly due to self-selection (e.g., people unable to work due to poor health are more likely to live in public housing), but living in unhealthy dwellings brings additional health risks.7

While giving tenants the opportunity to move into newer dwellings might be expected to bring many health benefits – for example, by reducing exposure to mould and improving thermal comfort7 – the overall impacts on health, wellbeing and health service use of such a large-scale and long-term redevelopment and change in distribution/mix of housing tenure (social/affordable vs. private market housing) are not well understood. In particular, the impact of large-scale redevelopment and tenant rehousing on the social fabric and cohesion of local communities and on the everyday lives of tenants8,9 might be expected to affect tenants’ health.10

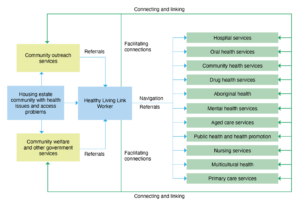

Most public housing in NSW, including the Waterloo estate and neighbouring Redfern estate, is owned by the Land and Housing Corporation within the NSW Department of Planning and Environment, which is the proponent of the Waterloo redevelopment. The Department of Communities and Justice manages the estates, while Sydney Local Health District (SLHD) within NSW Health is the main provider of health services for the area – including public hospital, community and mental health, ambulance, public health, and preventive services. SLHD established a Healthy Living program in Waterloo in 2017, employing a community-based link worker to help tenants connect with and navigate SLHD services (Figure 1).11

Figure 1. Service environment for the SLHD Healthy Living program11 (click figure to enlarge)

Source: Wiliams MF, et al. Qualitative case study: a pilot program to improve the integration of care in a vulnerable inner-city community. Int J Integr Care. 2022;2:15.11

A preliminary health impact assessment (HIA) of the redevelopment proposal commissioned by SLHD6 investigated the potential for some tenants to experience psychological distress following the announcement of the redevelopment and prior to them being rehoused. The HIA resulted in eight recommendations6, two of which are explored in this pilot project:

- The health needs and circumstances of a sample of Waterloo residents due to be rehoused could be assessed.

- Residents could be invited to participate in a longitudinal panel study to assess changes (both positive and negative) in the health and wellbeing of residents before, during and after the redevelopment project.6

This project, developed by the research team in collaboration with SLHD, aimed to trial methods for a future longitudinal study to a) assess how the redevelopment affects the health of tenants; and b) act on health needs identified throughout the redevelopment.

Methodology

We developed and trialled a method for assessing the health of social housing tenants in the Waterloo estate (intervention group), tenants in other parts of Waterloo, and tenants in the neighbouring suburb of Redfern (potential comparison group for a future longitudinal study). To explore ways of acting on unmet health needs identified through the health assessments, in partnership with SLHD, we also developed and trialled a referral system for connecting those tenants identified as being likely to have unmet health service needs with appropriate health services via the existing SLHD link worker. The research team intends to use the methods developed and trialled in the pilot project in a future, large-scale, longitudinal study.

We developed a self-report health questionnaire for the health assessment component to capture participants’ health status and behaviours, housing conditions, sense of community, and demographic information. Validated survey instruments were used where available, including the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10)12 and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C).13 The data dictionary codebook is provided in a supplementary file (S1), available from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24295477.

The invitation to participate in the study was emailed by two local community groups in December 2020, with data collection continuing until February 2021. The target sample size for the pilot project was 50, which is similar to that used in similar pilot projects.14,15 To be eligible, participants needed to be older than 18 years, living in social housing in Waterloo or Redfern, and proficient in English. Eligibility was assessed through a screening questionnaire that participants could complete either: a) online using the REDCap platform16; b) by telephone with a research assistant; or c) face-to-face with the link worker. After providing their consent (electronically or verbally) to participate in the study (including the referral system), eligible participants were invited to complete the health questionnaire, which was administered in the same way as the screening questionnaire (online, telephone or face-to-face). At the end of the health questionnaire, participants were asked to complete a feedback questionnaire, in which they were asked about their experience completing the health questionnaire. Participants who completed the health and feedback questionnaires were given or sent a physical or electronic A$25 gift card.

Completed health questionnaires were reviewed within 48 hours by a research team member. If a participant’s K10 score indicated a moderate or high risk of psychological distress (K10 score > 24) and/or their AUDIT-C score indicated a moderate or high risk of alcohol use disorder (AUDIT-C score > 3 for men; > 2 for others), then the participant was referred to the link worker. The link worker then attempted to contact the participant by telephone within 14 days to discuss the issue(s) and assist them with accessing appropriate healthcare and/or information, following existing protocols (Figure 1).11

The questionnaire and referral data were cleaned after data collection and referrals were complete. REDCap was used to generate descriptive statistics reported as frequencies and percentages.

Ethics approval and funding

The UNSW Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (approval number HC210355). This project received funding from the Healthy Urban Environments (HUE) Collaboratory 2020 Seed Funding Scheme.

Results

A total of 424 screening questionnaires were completed (405 online, 19 face-to-face, none by telephone), of which 310 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 286 online responses were identified as suspicious/fraudulent (e.g., due to providing a non-existent address), leaving 24 genuine participants who were invited to complete the health assessment (5 online, 19 face-to-face, none by telephone). The sample comprised a reasonable, though not fully representative, cross-section of the population: 12.5% were Aboriginal, English was not the first language for 25.0%, and 37.5% were female. Regarding employment, 37.5% were unemployed, 33.3% were retired, and 29.2% could not work due to sickness or disability. Two-thirds of participants lived in Waterloo, and the remainder in Redfern (proposed comparison area for future longitudinal study). There was a uniform distribution across all age groups 35 years and above, but no participants aged younger than 35 years.

Feedback from participants about the health assessment was positive, and there were no reported technical or comprehension issues. In the feedback questionnaire, one participant commented that doing the health assessment:

“…[it] helped me to reflect on what changes I need to make about my health. Like I have to make sure I eat more fruit and veggies and get more walking and exercise in each day. And to stop drinking alcohol.”

Of the 24 participants, half were referred to the link worker because they were classified as being at moderate or high risk of psychological distress and/or moderate or high risk of an alcohol use disorder, of which six were referred to one or more services (including occupational therapy, counselling and aged care).

Lessons learnt

The substantial number of suspicious responses may have been generated by an Internet bot able to evade REDCap’s bot protection technology. Lawlor et al.17 list several other tools that could be used to prevent and identify fraudulent responses in the future, e.g., identity verification.

The final sample size (n = 24) was well below the target of 50 participants. Potential explanations and solutions for the low response rate are listed in Table 1. In addition, data were collected during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which created additional challenges, including limiting face-to-face recruitment and data collection.

Table 1. Potential reasons and solutions for a low response rate

| Potential reasons | Potential Solutions |

| Inadequate publicity of the study. | Use other recruitment methods, e.g., intercept, bulk mail, letterbox drop, Short Message Service (SMS). |

| Distrust and/or survey fatigue among an over-researched community (as well as many previous academic studies, there have been many surveys/consultations conducted by government agencies and consultants since the redevelopment was first announced in 2015). | Use linked administrative data only, e.g., the Multi-Agency Data Integration Project (MADIP).18 |

| Insufficient incentive. | Increase financial incentives; offer non-monetary incentive(s). |

| Poor English proficiency. | Translate the health questionnaire and other study materials into other main community languages. |

Despite the low response rate, we were able to test the survey on a diverse range of tenants, with the notable exception of young adults (no one aged younger than 35 years participated). We were pleased to be able to recruit five participants aged older than 75 years (21%), given older adults have been noted to be more adversely affected by urban redevelopment and rehousing.19,20 To help achieve a representative sample in the full-scale study, recruitment and data collection methods will need to consider the diversity of the tenant population.

The comment by one participant that completing the survey prompted them to reflect on their health behaviours indicates a potential observer effect21 that will need to be controlled for when scaling up the study, for example, by using a quasi-experimental study design.22

It is worth noting that this study was enabled and strengthened by existing collaborations between the research team, SLHD and community groups. These included the Health Equity Research and Development Unit, a long-term collaboration between the UNSW Sydney Research Centre for Primary Health Care and Equity and SLHD, where two investigators (CS and FH) were based. Collaborating with the local health district made it easier to develop and incorporate the referral component of the study. Existing relationships with community groups facilitated engagement with tenants and helped to establish trust that the academic researchers may not otherwise have been able to achieve.

While it is impossible to generalise from such a small sample, the fact that the link worker referred one-quarter of participants to a health service indicates a potentially large unmet need for health services in the community. This finding highlights the need to ensure the link worker role can be adequately resourced when scaling up the study, as well as the importance of link workers or other person-centred integrated care interventions11 in social housing populations or other marginalised communities more generally. It may also add weight to calls for the health impacts of all future major social housing redevelopments to be comprehensively assessed and mitigation measures agreed to during the planning process and prior to approval being granted23; for example, through equity-focused health impact assessment.24

The findings from this pilot project can inform methods for assessing the health of social housing tenants, particularly during redevelopment, rehousing or other interventions.

Acknowledgements

The project was supported by SLHD, REDWatch and Counterpoint Community Services. We want to thank Mr Shane Brown OAM, SLHD Healthy Living Program Manager, for his valuable contributions to the study design, recruitment and data collection.

This paper is part of a special issue of the journal focusing on urban planning and development for health, which has been produced in partnership with the Healthy Populations and Environments Platform (formerly HUE Collaboratory) within Maridulu Budyari Gumal (the Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise, SPHERE).

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, invited.

Copyright:

© 2023 Standen et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Credit Suisse Research Institute. Global Wealth Report 2022. Zurich, Switzerland: CSRI; 2022 [cited 2023 Oct 3]. Available from: www.credit-suisse.com/media/assets/corporate/docs/about-us/research/publications/global-wealth-report-2022-en.pdf

- 2. Baker E, Lester L, Beer A, Bentley R. An Australian geography of unhealthy housing. Geogr Res 2019;57:40–51. CrossRef

- 3. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Housing assistance in Australia. Canberra: AIHW; 2023 [cited 2023 May 25] Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/housing-assistance/housing-assistance-in-australia/contents/social-housing-dwellings .

- 4. Sharam A, McNelis S, Cho H, Logan C, Burke T, Rossini P. Towards an Australian social housing best practice asset management framework. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited. Final report No. 367; 14 Oct 2021 [cited 2023 Oct 4]. Available from: www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/367

- 5. Bijen G, Piracha A. Future directions for social housing in NSW: new opportunities for ‘place’ and ‘community’ in public housing renewal. Aust Plan. 2017;54:153–62. CrossRef

- 6. Lilley D, Standen C, Lloyd J. Healthy Waterloo: A study into the maintenance and improvement of health and wellbeing in Waterloo [Unpublished report]. Sydney, Australia, 2019. Available from authors.

- 7. Thomson H, Thomas S, Sellström E, Petticrew M. Housing improvements for health and associated socio-economic outcomes: a systematic review. Campbell Syst Rev. 2013;9:1–348. CrossRef

- 8. Pinnegar S. Negotiating the complexities of redevelopment through the everyday experiences of residents: the incremental renewal of Bonnyrigg, Sydney. In: 6th State of Australian Cities Conference. Sydney, Australia: Analysis & Policy Observatory; 2013 [cited 2023 Oct 3]. Available from: apo.org.au/node/59790

- 9. Liu E. The wander years: estate renewal, temporary relocation and place (lessness) in Bonnyrigg, NSW. In: 6th State of Australian Cities Conference. Sydney, Australia: Analysis & Policy Observatory; 2013 [cited 2023 Jan 30]. Available from: apo.org.au/node/59780

- 10. L. F. Cooper H, Hunter-Jones J, Kelley ME, Karnes C, Haley D, Ross Z, et al. The aftermath of public housing relocations: relationships between changes in local socioeconomic conditions and depressive symptoms in a cohort of adult relocators. J Urban Heal. 2014;91:223–41. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Williamson MF, Song HJ, Dougherty L, Parcsi L, Barr ML. Qualitative case study: a pilot program to improve the integration of care in a vulnerable inner-city community. Int J Integr Care. 2022;2:15. CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. Anderson TM, Sunderland M, Andrews G, Titov N, Dear BF, Sachdev PS. The 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) as a screening instrument in older individuals. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:596–606. CrossRef | PubMed

- 13. Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption‐II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. Greaves S, Ellison AB, Ellison RB, Standen C, Rissel C, Crane M. Development of an online diary for longitudinal travel/activity surveys. Sydney, Australia: Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies, University of Sydney; 2014 [cited 2023 Oct 3]. Available from: hdl.handle.net/2123/19144

- 15. Haase AM, Gregersen T, Schlageter V, Scott MS, Demierre M, Kucera P, et al. Pilot study trialling a new ambulatory method for the clinical assessment of regional gastrointestinal transit using multiple electromagnetic capsules. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:1783–91. CrossRef | PubMed

- 16. REDCap consortium. US: REDCap; 2022. [cited 2022 Dec 8]. Available from: www.project-redcap.org/

- 17 Lawlor J, Thomas C, Guhin AT, Kenyon K, Lerner MD, Drahota A. Suspicious and fraudulent online survey participation: Introducing the REAL framework. Methodol Innov. 2021;14(3):205979912110504. CrossRef

- 18. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Multi-Agency Data Integration Project (MADIP). Canberra: ABS; 2023 [cited 2023 May 25]. Available from: www.abs.gov.au/about/data-services/data-integration/integrated-data/multi-agency-data-integration-project-madip

- 19. Morris A. ‘Communicide’: The destruction of a vibrant public housing community in inner Sydney through a forced displacement. J Sociol. 2019;55:270–89. CrossRef

- 20. Barrett EJ. The needs of Elders in public housing: Policy considerations in the era of mixed-income redevelopment. J Aging Soc Policy. 2013;25:218–33. CrossRef | PubMed

- 21 Kälvemark Sporrong S, Grøstad Kalleberg B, Mathiesen L, Andersson Y, Eidhammer Rognan S, Svensberg K. Understanding and addressing the observer effect in observation studies. Contemp Res Methods Pharm Heal Serv. 2022:261–70. CrossRef

- 22. Crane M, Bohn-Goldbaum E, Grunseit A, Bauman A. Using natural experiments to improve public health evidence: a review of context and utility for obesity prevention. Heal Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(1):48. CrossRef | PubMed

- 23. Keene DE, Geronimus AT. Weathering HOPE VI: The importance of evaluating the population health impact of public housing demolition and displacement. J Urban Heal. 2011;88:417–35. CrossRef | PubMed

- 24. Simpson S, Mahoney M, Harris E, Aldrich R, Stewart-Williams J. Equity-focused health impact assessment: A tool to assist policy makers in addressing health inequalities. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2005;25:772–82. CrossRef