Abstract

Public spaces influence the health and safety of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex, asexual and other sexual and gender-diverse (LGBTQIA+) communities. However, there is minimal research to demonstrate the link between inclusive urban policy and planning and the wellbeing of LGBTQIA+ communities. Consequently, in this perspective, we reflect on our project, which offered foundational work for understanding LGBTQIA+ experiences of public spaces in Australia’s three most populous urban centres – Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane. Our desk-based research approach provides a five-point evaluative framework to assess how local government areas (LGAs) accommodate LGBTQIA+ communities. We then present a recommendations framework for creating more inclusive local areas and public spaces. We propose that ‘usualising’ queerness in public spaces can lead to increased health and wellbeing for LGBTQIA+ communities.

Full text

Introduction

This perspective reports on the Australian component of a global effort that looks at more comprehensive and inclusive local government planning for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex, asexual and other sexual and gender diverse (LGBTQIA+) communities. Research has identified how public spaces can be exclusionary and sometimes dangerous for LGBTQIA+ individuals, families and communities.1 Meanwhile, public health research with LGBTQIA+ communities is still dominated by work on HIV reduction, the behaviours of gay men and men-who-have-sex-with-men, young people, and substance use.2-4 Significantly, some work has emerged with trans and gender-diverse people, queer women, and evolving spaces where LGBTQIA+ people interact, including online spaces and rural locations.5- 8 Yet, there is little research from a public health perspective acknowledging any links between urban policy and planning and wellbeing for LGBTQIA+ people.

Identifying this gap, we consider how to make public spaces safe, welcoming and inclusive for LGBTQIA+ people, that is, to ‘usualise’ queerness in the use and design of public spaces (as described further below). This is important for secure access to public spaces as essential dimensions of health and wellbeing, including:

- A sense of self-security when out and about in public spaces

- Safe access to social networks and interaction

- Safe access to employment and education opportunities

- The use of open spaces (e.g., parks) for therapeutic and recreational purposes.

This work is timely, with ever-increasing moves towards LGBTQIA+ equality in more countries. Yet, it is still a minority of countries that enjoy a full suite of legal protections for LGBTQIA+ people.9 Considering this context, this perspective reflects on how queerness can be usualised in public spaces for increased health and wellbeing.

The term ‘queering’ as an action and verb is applied to approaches in which LGBTQIA+ individuals, families and communities are expressly considered in social and political practice, including the use and design of public spaces. A history of social and legal exclusions shows that LGBTQIA+ people have specific spatial concerns.10-12 Formal social and legal equality may be improving in Australian federal and state/territory jurisdictions; however, this does not necessarily cascade into explicit recognition and inclusion at the local government level, nor for the acknowledgement of other intersecting communities (ethnic, socioeconomic, cultural, disabled and other). We posit that the flashpoint for such inclusion is local government policy, planning and public space design. We argue that those responsible for local planning and public space design should be aware that our local populations are diverse. This is where we further suggest moving from the practice of queering to the practice of ‘usualising’ queerness in public space, a term introduced by Catterall and Azzouz.13 We take usualising13 and define it within planning and design as being accommodating of all genders and sexualities from the start by making spaces and implementing policies that foundationally accommodate all.

Project

The project was conducted by researchers from Western Sydney University, UNSW Sydney and the University of Technology Sydney in collaboration with Maridulu Budyari Gumal: Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise (SPHERE) and global professional services (design, engineering) firm Arup. It provided foundational work for understanding LGBTQIA+ experiences of public spaces in Australia’s three most populous urban centres – Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane – which together account for approximately 61% of the national population14 and house the largest proportions of people who identify as LGBTQIA+. We had two aims:

- To explore if and how LGBTQIA+ people have been accommodated in these Australian agglomerations

- To understand how LGBTQIA+ people can be better accommodated in local council strategies and activities

We adopted a desk-based research approach with two parts:

- A thematic review of existing literature on the experiences of LGBTQIA+ people in Australian cities and the queering of public spaces, focusing on Australian-based literature.

- Building on the insights drawn from this literature, a review of current policies, strategies and plans operational in the local government areas (LGAs) that comprise the greater metropolitan areas of Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane. Local governments are the closest level of government to the community and are responsible for representing the interests of their communities and delivering local services and infrastructure.15 This review examined local councils’ actions to ensure the accommodation of LGBTQIA+ individuals, families and communities within their jurisdictions.

Our scope extended beyond well-known inner-city ‘gaybourhoods’ (areas widely recognised as home to LGBTQIA+ communities) and incorporated research and practice on LGBTQIA+ people living in suburbia. The findings of this research are available in the 2023 report, Queering Cities in Australia: Making Public Spaces More Inclusive through Urban Policy and Practice.16

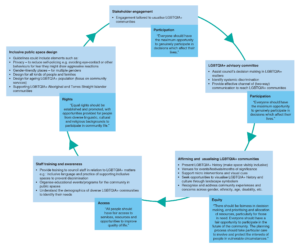

For this perspective, we highlight the insights from the review of local government policies and strategies (part 2). We developed a five-point evaluative framework based on the literature review (part 1), which included local and international best practice considerations and linked social justice principles legislated in New South Wales (NSW) (see Figure 1). Four social justice principles – equity, access, participation, and rights – are used to guide planning initiatives in NSW and are particularly apt for inclusive planning.17 Figure 1 outlines the five criteria of the evaluative framework, the policies, strategies and practices of LGAs, and how they feed into each other and respond to social justice principles. Ideally, LGAs could follow the continuous loop of the criteria from stakeholder engagement to inclusive public place design for best outcomes for LGBTQIA+ communities. Policies, strategies and activities from all LGAs in Sydney (31 LGAs), Melbourne (28 LGAs) and Brisbane (five LGAs) were evaluated against the criteria to understand if and how LGBTQIA+ people are being accommodated in local areas. The findings highlight geographical differences within and between the three cities and point to where and how wellbeing may be better enabled (at least in policy) for LGBTQIA+ people.

Figure 1. Local government policies and strategies review criteria: a five-point evaluative frameworka (click figure to enlarge)

a Social justice principles (equity, access, participation, rights) from NSW Division of Local Government (2013)17

Findings

We applied the five-point evaluative framework (Figure 1) to all LGAs across Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, and this section summarises the findings. The evaluation found that Melbourne is the most proactive city – per number and proportion of LGAs – in accommodating LGBTQIA+ people, followed closely by Sydney (see Figure 2 for best-performing LGAs in each city). The Victorian State Government developed a state-wide strategy in February 2022, Pride in our Future: Victoria’s LGBTIQ+ Strategy 2022–32, which outlines a plan to provide parameters for improving equity over the next 10 years.18 Accordingly, our evaluation found that Melbourne LGAs with LGBTQIA+ inclusive practices show more consistency in the language used and the types of actions taken. This includes establishing LGBTQIA+ advisory committees and developing LGBTQIA+ action plans.

Figure 2. Best-performing LGAs for LGBTQIA+ inclusive planning in Greater Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane (shown in black) (click figure to enlarge)

Source: Gorman-Murray A et al. Queering Cities in Australia: Making Public Spaces More Inclusive through Urban Policy and Practice (2023)16

We also found that across all three cities, LGAs closer to the inner-city core generally take a more proactive approach to usualising LGBTQIA+ accommodation in their strategies and activities. These areas are more likely to house traditional ‘gaybourhoods’, or other areas noted for sexuality and gender diverse populations, with above-average proportions of LGBTQIA+ people living there. However, LGBTQIA+ people often remain invisible in local planning in many suburban areas. Limited recognition means the councils’ strategies and plans are not meeting their needs.

While several councils have committed to creating an inclusive LGA for diverse communities in their community engagement plans, many do not specify the need to engage with LGBTQIA+ communities. Those councils that engage with LGBTQIA+ stakeholders do so through workshops, public forums, meetings, interviews, and surveys.

Those councils that have established LGBTQIA+ advisory committees tend to have more strategies and activities in the other criteria. These advisory committees provide feedback and input to the council, which ensures the voices of LGBTQIA+ people are heard and better accommodated. In Melbourne, most of these advisory committees are also tasked with developing an LGBTQIA+ action plan.

In terms of our five criteria outlined in Figure 1, the criterion that councils are most likely to engage in is affirming and usualising LGBTQIA+ communities. The most common activity across all cities is holding community events celebrating LGBTQIA+ communities. In addition, using visual cues, such as raising rainbow flags on important LGBTQIA+ dates and creating rainbow road crossings, are very popular. In Sydney and Melbourne, multiple councils are proactive in celebrating LGBTQIA+ events and dates yet do not actively engage in the other four criteria. This finding suggests that while organising events and using visual cues may be important acts of recognition and usualisation, they are also perhaps the most expedient means for councils to show their support for LGBTQIA+ communities. However, without meaningful action in other aspects of community engagement and use of public spaces, these visual cues can be critiqued as ‘rainbow washing’ – that is, using rainbow symbolism to suggest support for LGBTQIA+ inclusion, but without further effort or tangible outcomes.19. Careful consideration of the everyday pragmatic needs of LGBTQIA+ people in broader local planning and council practices is important for accommodating all communities within their jurisdiction.

While Melbourne-based councils engage more proactively in training and awareness activities than councils in Sydney and Brisbane, our findings suggest that councils could employ more effort across the board. Training activities include raising awareness of the importance of inclusive practices and language. Some training might target staff that work with LGBTQIA+ people. Some councils also provide staff and the community with information on inclusive language and explanations of LGBTQIA+ terminology.

Generally, we found that very few councils have strategies or design guidelines that specifically address the issues and needs of LGBTQIA+ people when using public spaces or facilities. While inclusive and accessible strategic planning is provided in a more generic capacity across social groups, little consideration is given to the specific needs of LGBTQIA+ people.

Further work and framing

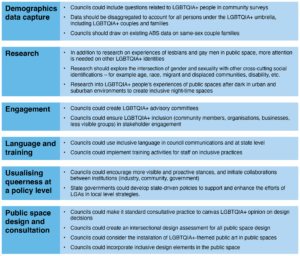

From this research, we developed a recommendations framework for creating more inclusive local areas and public spaces (see Figure 3). These recommendations will be tested and refined in a new project working with the Greater Cities Commission on LGBTQIA+ inclusive planning in local government in the Six Cities Region of NSW, which is a government-designated interconnected urban region that includes Newcastle, the Central Coast, Wollongong and the three regions within Sydney – Australia’s largest urban mega-region.

Figure 3. Recommendations framework (click figure to enlarge)

Through engaged research, the next stage of this program of work will develop practical frameworks for consultation, usualisation and implementation of queering approaches to the design of public spaces, especially by local governments. Ultimately, this will help us better understand how queerness can be usualised in public spaces for increased health and wellbeing.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the project team and funders. Investigator team: AGM, JP, EDL, AV, RC, Jacqueline Jones, and Carly Choi. AGM received funding for the research from the Healthy Populations and Environments Platform (formerly the Healthy Urban Environments Collaboratory), within Maridulu Budyari Gumal: Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise (SPHERE).

This paper is part of a special issue of the journal focusing on urban planning and development for health, which has been produced in partnership with the Healthy Populations and Environments Platform, SPHERE. JP and EDL were guest editors for the special issue. JP and EDL were not involved in the review of or decisions on this manuscript.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, invited.

Copyright:

© 2023 Gorman-Murray et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Doan, P.L. (Ed.). Planning and LGBTQ Communities: The Need for Inclusive Queer Spaces (1st ed.). Routledge; 2015.

- 2. Sweeney SO, Cheng Y, Botfield JR, Bateson DJ. Renewal of the National Cervical Screening Program: health professionals’ knowledge about screening of specific populations in NSW, Australia. Public Health Res Pract. 2022;32(1):e31122104. CrossRef | PubMed

- 3. Demant D, Hides LM, Kavanagh DJ, White KM. Young people’s perceptions of substance use norms and attitudes in the LGBT community. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2021;45:20–5. CrossRef | PubMed

- 4. Jaspal R, Lopes B. Psychological wellbeing facilitates accurate HIV risk appraisal in gay and bisexual men. Sex Health. 2020;17(3):288–95. CrossRef | PubMed

- 5. Alba B, Lyons A, Waling A, Minichiello V, Hughes M, Barrett C, et al. Health, well‐being, and social support in older Australian lesbian and gay care‐givers. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28(1):204–15. CrossRef | PubMed

- 6. Abraham E, Chow EPF, Fairley CK, Lee D, Kong FYS, Mao L, et al. eSexualHealth: preferences to use technology to promote sexual health among men who have sex with men and trans and gender diverse people. Front Public Health. 2023;12(10):1064408. CrossRef | PubMed

- 7. Heard E, Oost E, McDaid L Mutch A, Dean J, and Fitzgerald L. How can HIV/STI testing services be more accessible and acceptable for gender and sexually diverse young people? A brief report exploring young people's perspectives in Queensland. Health Promot J Austr. 2020;31(1):150–5. CrossRef | PubMed

- 8. Easpaig B, Reynish T, Hoang H, Bridgman H, Cornvinus-Jones S, Auckland S. A systematic review of the health and health care of rural sexual and gender minorities in the UK, USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Rural Remote Health. 2022;22(3):6999. CrossRef | PubMed

- 9. Herre B, Arriagada P, Roser M. LGBT+ rights. UK: OurWorldInData; 2023 [cited 2023 Sep 5]. Available from: ourworldindata.org/lgbt-rights

- 10. Broto VC. Queering participatory planning. Environment and Urbanization. 2021;33(2):310–329. CrossRef

- 11. Frisch M. Planning as a heterosexist project. Journal of Planning Education and Research. 2002;21(3):254–66. CrossRef

- 12. Nash CJ, Maguire H, Gorman-Murray A. LGBTQ communities, public space and urban movement. Towards mobility justice in the contemporary city. In: Cook, N, & Butz, D, editors. Mobilities, Mobility Justice and Social Justice, 1st ed. Routledge; 2018, pp. 187–200.

- 13. Catterall P, Azzouz A. Queering planning policy. Town and Country Planning. 2021;90(10):298–302. CrossRef

- 14. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Regional population. Canberra: ABS; 2023 [cited 2023 Nov 11]. Available from: www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/regional-population/latest-release

- 15. Prior J, Herriman J. The emergence of community strategic planning in New South Wales, Australia: Influences, challenges and opportunities. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance. 2010;(7):45–77. CrossRef

- 16. Gorman-Murray A, Prior J, de Leeuw E, Jones J, Vincent A, Cadorin R, et al. Queering cities in Australia. Australia: Arup; 2023. [cited 2023 Nov 9]. Available from: www.arup.com/perspectives/publications/research/section/queering-cities-in-australia

- 17. NSW Division of Local Government, Department of Premier and Cabinet. Integrated Planning and Reporting Manual for Local Government in NSW. Sydney: NSW Division of Local Government; 2013 [cited 2022 Feb 22]. Available from: www.olg.nsw.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/Integrated-Planning-and-Reporting-Manual-for-local-government-in-NSW.pdf

- 18. Victorian Government. Pride in our future: Victoria’s LGBTIQ+ strategy 2022–32. Victoria: VIC Government; 2022 [cited 2023 Nov 9]. Available from: www.vic.gov.au/pride-our-future-victorias-lgbtiq-strategy-2022-32

- 19. Czepanski D. Rainbow washing is a thing, here’s why it needs to stop. Australia: The Urban List: 2022 [cited 2022 Mar 12]. Available from: www.theurbanlist.com/a-list/rainbow-washing