Abstract

Successful research-policy partnerships rely on shared vision, dedicated investment, and mutual benefits. To ensure the ongoing value of chronic disease prevention research, and support research translation and impact, Australia needs funding, university, and policy systems that incentivise and support emerging leaders to drive effective partnerships.

.

Full text

Introduction

Combating the high prevalence rates of chronic disease is a national and global priority1, yet for many conditions, the implementation of effective and sustainable solutions supported by evidence remains elusive.2 Collaborative partnerships between researchers and other stakeholders are an important instrument for enhancing policy and program effectiveness.3,4 For example, research-policy partnerships can generate more applied, policy-relevant research, as well as support evidence mobilisation for system change.3,5,6

In this perspective, we consider some of the core elements of successful research-policy partnerships in chronic disease prevention and propose how the Australian research funding systems, university sector, and applied prevention systems could better support our next generation of research leaders to participate in and lead such collaborations. Supporting emerging leaders will enable the ongoing evolution and success of research partnerships, contributing to research impact and co-benefits for early and mid-career researchers (EMCRs), policymakers, and the population.7 To identify elements of successful research-policy partnerships, we compiled and synthesised findings from a brief review of the international literature (See Supplementary file 1, available from: osf.io/d2jgs/?view_only=e6e66c9092cb4d86b63e54c663ee931f), our own experience, and the shared experience of colleagues leading established partnerships: Professor Andrew Wilson from The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre (Prevention Centre)8, and Professors Anna Peeters, Louise Baur and Luke Wolfenden, who together with authors LR and HS co-founded the Collaboration for Enhanced Research Impact (CERI).9 Suggestions for systemic support for emerging leaders are derived from iterative dialogues (all authors) on the needs and challenges faced by EMCRs, and some of the existing gaps and opportunities.

Successful chronic disease prevention research-policy partnerships

Research-policy partnerships in chronic disease prevention, and more broadly in public health and health promotion, can take many forms, and vary by context, aims, stakeholders involved, and forms of collaboration.4,6 Their development may be opportunistic or strategic, emerge organically or be purposefully planned, be researcher or policy-led, or both. Success often relies on a shared vision, common goals and agreed programs of work that bring mutual benefits.6,10,11

Successful partnerships are usually underpinned by relationship-based factors like mutual understanding and trust, as well as practical factors such as sound governance and explicitly agreed processes.5,12 Collaborations that entail high levels of co-design and co-production also require substantial investments of time, resources, and capacity building. The skills, time, and resources required to initiate and support co-design and co-production are often underestimated by research organisations and stakeholders.10

There is still much to learn about sustaining successful research-policy partnerships.4,5,10 Creating opportunities and providing system-level capability and capacity building for the next generation of prevention leaders is essential. Table 1 outlines the core elements required for effective research-policy partnerships and the types of challenges that often arise. Suggestions for supporting emerging leaders in chronic disease prevention research to conduct effective partnerships are outlined further below.

Table 1. Attributes and challenges of successful research-policy partnerships

| Common elements for success | Common challenges |

Shared vision and contribution:

Sound governance:

Substantial investment:

|

Longer-term established partnerships can be affected by significant changes in partners’ organisational and contextual circumstances e.g.:

Emerging developments can offer unanticipated benefits or create new

Establishment of new partnerships may take longer than anticipated with loss of momentum e.g.:

|

Systemic support for emerging leaders to do chronic disease prevention partnership research

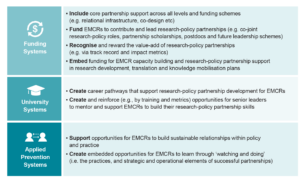

Australian prevention system stakeholders, including funding agencies, universities, and prevention policy and program agencies, could augment their support for EMCRs in forming effective research-policy partnerships (Figure 1). Such partnerships will then be fostered to hold many of the elements described in Table 1. While we recognise that many examples of such initiatives exist, we propose this support could be more explicit and systemic to enhance the policy and practice relevance and impact of future Australian prevention research.

Figure 1. Summary of recommendations to support emerging leaders in chronic disease prevention research to build research-policy partnerships (click figure to enlarge)

EMCR=early and mid-career researchers.

Funding systems

A greater proportion of overall research funding must be allocated to the type of multiagency population-based studies on which effective chronic disease prevention relies. This could be achieved with new dedicated funding streams, such as the former National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) partnership centres scheme that established the Prevention Centre13, and more relevant grant assessment criteria for population health research.14 This could also include a dedicated public health and prevention stream for initiatives such as the NHMRC’s Research Translation Centres15, as well as capitalising on the Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Program.

Further, many EMCRs are employed in volatile fixed-term positions, requiring them to prioritise academic outputs, research dissemination, and short-term impact to remain competitive for grants and positions. Systems for funding prevention research need to work with emerging leaders and other stakeholders to identify effective ways to incentivise and enable them to build effective partnerships across applied settings such as “researcher in residence” models. Funding criteria should also acknowledge the opportunity costs in academic advancement that can occur with investment in research-policy partnerships. Funding systems should incorporate metrics assessing partnership development in track record and impact evaluations, and where appropriate, grant panels should acknowledge and assess EMCR involvement in research-policy partnerships. This may involve rating both impact (as in the NHMRC schemes) and the progress towards impact.

Finally, funded knowledge mobilisation strategies offer key pathways for researchers and policymakers to connect. A good knowledge mobilisation and science communication strategy, especially one developed early and in collaboration, can open researcher dialogue with policymakers, build opportunities for co-production, and help to embed and maintain mutually beneficial partnerships.16 For example, the Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF)-funded ‘Boosting Prevention’ grants (2018 – 2020) awarded through the Prevention Centre included explicit requirements for early development of knowledge mobilisation plans and central support for EMCR capacity building from a dedicated Knowledge Mobilisation lead.17 CERI9 has enabled NHMRC Centres of Research Excellence (CREs) to collaborate with the Prevention Centre to provide coordinated and shared EMCR capacity building, including knowledge mobilisation and science communication. Additional funding could significantly expand such initiatives. Further support and incentives to upskill and enable researchers to habitually develop and implement knowledge mobilisation plans are also needed.

University systems

The university system supports a range of teaching and research career pathways. In addition to providing partnership support for research-only and teaching/learning positions, there is potential to expand new academic career pathways focused on leading research-policy partnerships. We propose such roles (e.g., co-funded roles focused on partnership research) should be more widely available as university-funded public health ‘backbone’ positions. These might differ from or enhance current embedded researcher models by providing additional, formally recognised programs, work plans, training, and mentoring on partnership building. Collaborative models with state or regional prevention services, such as conjoint research-policy or program positions or secondments can create environments where research-policy collaborations are expected and research findings are more readily translated.18 Dedicated policy-partnership roles can reward the time and specialist skills required, encourage EMCRs with interest and talent in stakeholder engagement, and invite senior academics with professional policy experience into universities. Such career pathways can help universities meet their strategic goals of engagement and impact, while also better supporting EMCRs in research-only tracks who are trying to ‘do it all’.

At the more granular school or unit level, many senior leaders are incredibly generous in sharing opportunities for EMCR development in partnership building, but the experience is not ubiquitous. We also recognise the strategic management of partnerships within research groups can be fickle. Care must also be taken that learning opportunities do not hinder meeting project goals or the needs of partners. Good mentorship and opportunities to “learn by doing” with appropriate support are essential, as well as recognition of potential opportunity costs for senior leaders. We suggest that including ‘partnership mentoring’ in research funding, leadership training for senior academics, and metrics for track record and promotion of senior academics would facilitate wider opportunities for embedding partnership roles for EMCRs.

Applied chronic disease prevention systems

We recognise the importance of emerging leaders working in chronic disease prevention research to better understand the complexities of applied policy and practice. Opportunities may include training and/or direct exposure to contexts across core elements of the Australian prevention system, including population health policy and practice, healthcare services, nongovernment organisations, and the private sector. Survey and anecdotal feedback from the Prevention Centre’s national emerging leaders network also highlights great interest among EMCRs, policy officers and practitioners to connect, collaborate, and learn from each other.

We believe there is a growing appetite among EMCRs to better understand the theory, processes, steps, and opportunities of research-policy partnerships. This should include addressing the governance mechanisms for successful partnerships from both research and policy perspectives, co-production theory and methods, and science communication. Some training opportunities exist (often run by universities or independent organisations) and could be expanded and more widely supported with in-kind contributions (e.g., from industry partners).

In addition to supporting training opportunities, the wider prevention system could further invest in new opportunities for emerging research leaders to initiate, develop, and sustain research-policy partnerships. Mechanisms can include dedicated research engagement roles embedded in policy agencies or healthcare services to facilitate partnership development or other research collaborations. Such roles can have a dual purpose, i.e., to support partnerships and contribute to local EMCR capacity building.

Conclusion

Engaging with stakeholders, such as those linked with CERI and the Prevention Centre, to collaboratively identify and tailor pragmatic steps towards validating and acting on the recommendations outlined in Figure 1 is now essential. Such efforts will support the premise that all prevention systems will see greater returns on investment from future research that addresses priority-driven, policy-relevant questions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Professor Andrew Wilson from The Prevention Centre, and Professors Anna Peeters, Louise Baur and Luke Wolfenden, who co-founded CERI with co-authors LR and HS. Professors Wilson, Peeters, Baur, and Wolfenden provided great reflection and prompted valuable discussion on what makes and hinders successful research-policy partnerships that informed this paper. We would also like to thank Anita Maepioh and Faye Forbes for their assistance with searching, preparing the summary tables, and summarising literature themes.

BH was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE230100704). LR and The Prevention Centre were supported through the NHMRC Partnership Centre grant scheme (Grant ID: GNT9100003) with the Australian Government Department of Health, ACT Health, Cancer Council Australia, NSW Ministry of Health, Wellbeing SA, Tasmanian Department of Health, and VicHealth. MF was supported by an NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence (No. APP1153479) – ‘the National Centre of Implementation Science’ and the Population Health Program (Hunter Medical Research Institute). SN was supported by the CRE in Food Retail Environments for Health (RE-FRESH) (APP1152968).. KK and VB are researchers within the CRE in Translating the Early Prevention of Obesity in Childhood (GNT2006999). HS was supported by the CRE in Health in Preconception and Pregnancy (GNT1171142).

This paper is part of a special issue of the journal focusing on: ‘Collaborative partnerships for prevention: health determinants, systems and impact’. The issue has been produced in partnership with the CERI, a joint initiative between The Prevention Centre and NHMRC CREs. The Prevention Centre is managed by the Sax Institute in collaboration with its funding partners. BH, SN and CH were guest editors of the issue. They had no involvement in the review of or decisions on the manuscript

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, invited.

Copyright:

© 2024 Hill et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Australian Department of Health. National Preventive Health Strategy 2021–2030. Canberra: Australian Government; 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 03]. Available from: www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/12/national-preventive-health-strategy-2021-2030_1.pdf

- 2. Swinburn BA, Kraak VI, Allender S, Atkins VJ, Baker PI, Bogard JR. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: The Lancet Commission report. The Lancet. 2019;393(10173):791–846. CrossRef | PubMed

- 3. Faghy MA, Whitsel L, Arena R, Smith A, Ashton RE. A united approach to promoting healthy living behaviours and associated health outcomes: a global call for policymakers and decisionmakers. J Public Health Policy. 2023;44:285–99. CrossRef | PubMed

- 4. Hoekstra F, Mrklas KJ, Khan M, McKay RC, Vis-Dunbar M, Sibley KM, et al. A review of reviews on principles, strategies, outcomes and impacts of research partnerships approaches: a first step in synthesising the research partnership literature. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(51):23. CrossRef | PubMed

- 5. Williamson A, Tait H, Jarjali FE, Wolfenden L, Thackway S, Stewart J, et al. How are evidence generation partnerships between researchers and policy-makers enacted in practice? A qualitative interview study. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17(41):11. CrossRef | PubMed

- 6. Wutzke S, Rowbotham S, Haynes A, Hawe P, Kelly P, Redman S, et al. Knowledge mobilisation for chronic disease prevention: the case of The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(109):17. CrossRef | PubMed

- 7. Evans, M.C., Cvitanovic, C. An introduction to achieving policy impact for early career researchers. Palgrave Commun. 2018;4:88. CrossRef

- 8. The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. A partnership approach to chronic disease prevention. Sydney: The Sax Institute; 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 03]. Available from: preventioncentre.org.au/

- 9. The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. Collaboration for Enhanced Research Impact (CERI). Sydney: The Sax Institute; 2023 Oct [cited 2023 Oct 03]. Available from:preventioncentre.org.au/work/collaboration-for-enhanced-research-impact-ceri/

- 10. van der Graaf P, Kislov R, Smith H, Langley J, Hamer N, Cheetham M, et al. Leading co-production in five UK collaborative research partnerships (2008–2018): responses to four tensions from senior leaders using auto-ethnography. Implement Sci. 2023;4(12):15. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Williams C, Pettman T, Goodwin-Smith I, Tefera YM, Hanifie S, Baldock K. Experiences of research-policy engagement in policy-making processes. Public Health Res Practice. 2024; 34(1):e33232308. CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. Erismann S, Pesantes M, Beran D, Leuenberger A, Farnham A, Gonzalez de White MB, et al. How to bring research evidence into policy? Synthesizing strategies of five research projects in low-and middle-income countries. Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;19(29):13. CrossRef | PubMed

- 13. The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. Lessons from a decade of The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. Sydney: The Sax Institute; 2023 Oct [cited 2023 Oct 03]. Available from: preventioncentre.org.au/resources/lessons-from-a-decade-ofthe-australian-prevention-partnership-centre/

- 14. Collaboration for Enhanced Research Impact. Submission on improving alignment and coordination between the Medical Research Future Fund and Medical Research Endowment Account. Sydney, Australia: The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre; 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 03]. Available from: preventioncentre.org.au/resources/submission-on-improving-alignment-and-coordination-between-mrff-and-mrea/

- 15. National Health and Medical Research Council. Recognised research translation centres. Canberra: Australian Government; 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 3]. Available from: www.nhmrc.gov.au/research-policy/research-translation/recognised-research-translation-centres

- 16. Irving MJ, Pescud M, Howse E, Haynes A, Rychetnik L. Developing a systems thinking guide for enhancing knowledge mobilisation in prevention research. Public Health Res Pract. 2023;33(2):e32232212. CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. MRFF Boosting Preventive Health Research Program. Syndey: The Sax Institute; 2019 Mar [cited 2024 Feb 22]. Available from: preventioncentre.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/MRFF_boosting_preventive_Program_FINAL.pdf

- 18. Wolfenden L, Yoong S, Wiliams CM, Durrheim DN, Gillham K, Wiggers J. Embedding researchers in health service organizations improves research translation and health service performance: the Australian Hunter New England Population Health example. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;85:3–11. CrossRef | PubMed