Abstract

Objectives and importance of study: This study analyses Australian healthy hospital retail policies to identify the similarities and differences in the policies and policy implementation processes. The potential impact of the different policy components on dietary behaviours were examined via a scoping review.

Study type: Policy analysis and scoping review.

Methods: Healthy retail policy documents and policy implementation guidelines were identified via a grey literature search on Department of Health websites of all Australian jurisdictions. Policy components and policy implementation processes were extracted and analysed for similarities and differences. The potential effectiveness of the different policy components on purchasing and/or dietary behaviour were identified via a scoping review of the academic literature, conducted in March 2023 across seven electronic databases and Google Scholar. The scoping review included studies reporting the impacts of healthy food retail interventions implemented in hospitals. No timeframe restriction was applied for both the grey literature search and the scoping review.

Results: All Australian jurisdictions, except Tasmania, have implemented jurisdiction specific healthy retail policies in public hospital settings. There are similarities and difference in the policy components and implementation design across the jurisdictions. Similarities included the policy scope, use of a traffic light system to classify the nutritional healthiness of food and beverages for sale, and the standards used to determine the mix of healthy and unhealthy food availability. These similarities allowed sharing of resources across some jurisdictions. There is limited evaluation of policy impacts on purchase and/or consumption behaviours. Twenty of 27 studies identified via the scoping literature review examined interventions similar to the Australian policies and showed that these policies could result in increased purchase of healthier products among staff and visitors. Key implementation success factors include strong support for the policy from all stakeholders, practical implementation support resources, and impacts on retailer profitability.

Conclusions: The healthy hospital retail policies implemented across Australian jurisdictions could encourage healthier food and beverage purchases among staff and visitors. Evaluation of the policies could facilitate further refinement to enhance effectiveness and translation of learnings to international contexts.

Full text

Introduction

In 2018, unhealthy diets were the third leading modifiable risk factor for disability, chronic diseases, and premature mortality in Australia.1 While shaped by an intricate interplay of determinants2, unhealthy dietary behaviours are impacted by food environments, including retail food environments.3,4 Current literature highlights that retail food environments are dominated by the promotion and availability of foods and beverages (F&B) that are energy-dense and high in sugar, salt and fat, which has a negative impact on population diets.5,6 Modifying the food retail environment using the marketing techniques of product (changing the availability of specific products), price, promotion and placement can help consumers make healthier food purchases.7,8

Public hospitals are regarded as high-profile government institutions that should play a key role in promoting and providing their staff, patients and visitors with healthy F&B options.9,10 Furthermore, given that public hospitals are government-funded, it is critical that they align with public health imperatives. While there are nutrition and quality standards for food provided to inpatients, F&B sold in hospital retail outlets are not covered by these standards.11 To address this, state and territory jurisdictions in Australia have implemented healthy hospital retail policies in government-managed healthcare facilities to enhance the healthiness of food retail environments.9,10,12 These policies aim to increase the availability, accessibility and promotion of healthier F&B for staff and visitors in public hospital settings.9,10,12 To date, no studies have examined these policies and their implementation designs in detail and assessed their impacts on F&B purchasing behaviours among hospital staff and visitors. This study aimed to: 1) analyse the policy components of the healthy hospital retail policies implemented in Australian jurisdictions; 2) identify the similarities and differences across these policies; and 3) assess their potential impacts on dietary behaviours. We undertook a policy analysis of the healthy hospital retail policies across Australia, and a scoping review of the global academic literature to identify the potential impacts of the Australian policies on the dietary behaviours of staff and visitors within hospital settings.

Methods

Policy analysis of Australian healthy food retail policies

As public hospitals in Australia are funded and managed by state and territory governments, publicly available hospital retail policies for public hospitals were identified via a targeted grey literature search on the health department websites of each Australian jurisdiction. The search was conducted in September 2022 and updated in September 2023, using keywords: “hospital*”, “healthcare facilit*”, “healthy food and drinks”, “policy”, “guideline*”, “directive”. The most recently available policy versions were identified, and the following details were extracted: policy scope and components; system used for nutritional quality assessment of F&B available for sale; availability standards of F&B for sale; implementation mandates and compliance timelines; implementation steps; implementation support mechanisms; monitoring and evaluation processes; and stakeholder involvement. Policy stakeholders verified the accuracy of the key policy details extracted and the implementation process (Appendix A, available from: figshare.com/s/82395ca5b89253d98822).

Scoping review of the effectiveness of healthy food retail interventions in hospitals

A scoping literature search was conducted in March 2023 across seven electronic databases, without time restriction. Keyword searches focused on health-promoting F&B retail intervention(s) in hospital settings in any country (search strategy detailed in Appendix A, available from: figshare.com/s/82395ca5b89253d98822). The following inclusion criteria were applied: 1) settings – food outlets, and vending machines within hospital settings; 2) intervention – retail interventions that aimed to increase the availability and/or promotion of healthy F&B options and/or decrease the availability and/or promotion of unhealthy options available for sale; and 3) outcomes – changes in the food retail environments, purchasing/consumption behaviours of staff and visitors, anthropometric measures, financial impacts on retailers, and facilitators and barriers to implementation. Studies from all countries with any design were included, except conference abstracts. Studies were excluded if they targeted specific populations with a health condition. One author conducted data screening. One author undertook data extraction with 50% of the data checked by a second author. A senior researcher resolved any discrepancies. Data extraction included: study design, intervention descriptions, settings, target population, comparators, intervention implementation and evaluation details, impacted F&B categories, nutrient classification scheme, changes in purchasing/consumption behaviours, anthropometric measures, retailer profitability, barriers and facilitators to implementation, and methods used to measure outcomes. The extracted data was compared to the Australian policies to identify evidence for the effectiveness of the different policy and implementation components.

Results

Australian healthy food retail policies in hospital settings

Seven Australian state and territory jurisdictions have introduced a healthy hospital retail policy; Tasmania is the only jurisdiction without such policy. These policies were originally developed from 2000–2010; however, all have been recently (2016–2023) revised, with a greater focus on making them mandatory and providing improved implementation support.9,10,12-16 All jurisdictions except New South Wales (NSW) have mandated that F&B sold and promoted in hospital retail outlets adhere to jurisdiction-specific policies; however, the timeline for mandatory implementation varies.9,10,12-15 In NSW, policy implementation is recommended but not mandated16 (see Table 1, Appendix B, available from: figshare.com/s/82395ca5b89253d98822).

Table 1. Summary of healthy hospital retail policies in Australian state/territory jurisdictions

| Jurisdictions and policy reference | ACT15 | NSW16 | NT14 | QLD10 | SA13 | VIC9 | WA12 |

| Date of most recent policy | 2016 | 2017 | 2017 | 2022 | 2023 | 2021 | 2021 |

| Mandatory implementation | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dates for mandatory implementation | 2016 | NR | NR | Beverages: 2019 Food: 2020 |

2010 | Beverages: 2022 (Phase 1) Food: 2023 (Phase 2) |

2008 |

| Policy scope | |||||||

| Hospital-owned & leased food outlets | Both | Hospital-owned only | NR | Both | Hospital-owned only | Hospital-owned only | Both |

| Hospital-owned & leased vending machines | Both | Hospital-owned only | NR | Both | Hospital-owned only | Both | Both |

| Staff and visitor catering | Staff catering only | Both | Both | Both | Both | Both | Both |

| F&B classification system used | Traffic light | Australian Dietary Guidelines, Health Star Rating | Traffic light | Traffic light | Traffic light | Traffic light | Traffic light |

| System used to assess nutritional standard | Australian Dietary Guidelines | Australian Dietary Guidelines | Australian Dietary Guidelines | Australian Dietary Guidelines | Australian Dietary Guidelines | Australian Dietary Guidelines | Australian Dietary Guidelines |

| Tools to assess nutritional standards | NR | PHIMS Nutrition standard | NR | FoodChecker | FoodChecker | FoodChecker | NR |

| Portion size standardsa | Red: smallest portion sizes Amber: avoid large portion sizes Green: NR |

Occasional: Reference maximum portion sizes, e.g., sweet biscuits (50 g), diet drinks (500 ml), etc. Everyday: Reference maximum portion sizes, e.g., packaged ready-to-eat meals (45 0g), lightly salted popcorn (50 g), etc. |

NR | Red: smallest portion sizes Amber: avoid large portion sizes Green: Portion sizes based on food group, e.g. dried roasted almond ≤ 35 grams, commercial flavoured milk ≤ 375 millilitres |

Red: smallest portion sizes Amber: avoid large portion sizes Green: Portion sizes based on food group, e.g. dried roasted almond ≤ 30 grams, commercial flavoured milk ≤ 300 millilitres |

Red: smallest portion sizes Amber: avoid large portion sizes Green: Portion sizes based on food group, e.g. dried roasted almond ≤ 35 grams, commercial flavoured milk ≤ 300 millilitres |

Red: smallest portion sizes Amber: avoid large portion sizes Green: Portion sizes based on food group, e.g. dried nut ≤ 40 grams, commercial flavoured milk ≤ 300 millilitres |

| Food availability standardsb | Red: ≤ 20% Amber: No specific requirement Green: ≥ 50% |

Occasional: ≤ 25% Everyday: ≥ 75% |

Red: ≤ 20% Amber: No specific requirement Green: ≥ 50% |

Red: ≤ 20% Amber: No specific requirement Green: ≥ 50% |

Red: ≤ 20% Amber: No specific requirement Green: ≥ 50% |

Red: ≤ 20% Amber: No specific requirement Green: ≥ 50% |

Red: ≤ 20% Amber: No specific requirement Green: ≥ 50% |

| Beverage availability standardsc | Red: 0% Amber: ≤ 20–25% artificially sweetened beverages Green: ≥ 50% |

Occasional: ≤ 25% Everyday: ≥ 75% |

Red: ≤ 20%, 0% sugary beverages Amber and green: ≥ 80%, with green: ≥ 50% |

Red: 0% Amber: ≤ 20 artificially sweetened beverages Green: ≥ 50% |

Red: ≤ 10%, 0% in vending machines in areas frequented by children Amber: ≤ 20 artificially sweetened beverages Green: ≥ 50% |

Red: 0% Amber: ≤ 20 artificially sweetened beverages Green: ≥ 50% |

Red: 0% Amber: 25% artificially sweetened beverages Green: ≥ 50% |

| Implementation support resources | |||||||

| Statewide implementation support agency/officer | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR |

| Menu assessment tool | NR | PHIMS Nutrition standard | NR | FoodChecker | FoodChecker | FoodChecker | NR |

| Audit mechanism | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Published evaluation report | NR | NR | NR | Yes17 | Yes18 | Yes19 | Yes20 |

ACT = Australian Capital Territory; F&B = food and beverages; NR = not reported; NSW = New South Wales; NT = Northern Territory; PHIMS = Public Health Information Management System; QLD = Queensland; SA = South Australia; VIC = Victoria; WA = Western Australia.

Notes: Shaded boxes indicate similar policy components to other jurisdictions in the same row

a Standards regarding the portion size of F&B from different categories are provided in retail outlets

b Standards regarding what proportion of food from different categories are provided in retail outlets

c Standards regarding what proportion of beverages from different categories are provided in retail outlets

Many similarities exist between policy components across the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), Northern Territory (NT), Queensland, South Australia (SA), Victoria, and Western Australia (WA). All jurisdictions assess F&B nutritional healthiness based on the Australian Dietary Guidelines (ADG)21, and all jurisdictions except NSW classify F&B into three ‘traffic light’ categories. The traffic light system is a colour-coded approach used to indicate F&B nutritional healthiness. Unhealthy options are classified as ‘red’, healthier options as ‘amber’ and the healthiest options as ‘green’. Several policies advised that ‘red’ items should be provided in the smallest portion size available, and retail outlets should avoid providing ‘amber’ items in large portion sizes. The jurisdictions that use the traffic light system also use similar availability standards for foods – ‘red’ options should make up ≤ 20% of available food options, and ‘amber’ and ‘green’ options should account for ≥ 80%. Five jurisdictions (ACT, NT, Queensland, Victoria, WA) have mandated the removal of all ‘red’ beverage options or sugary beverages. Four jurisdictions (Queensland, SA, Victoria, WA) specify availability standards for artificially sweetened beverages, with Queensland and Victoria limiting their availability to 20% of available beverage options and SA and WA limiting it to 25%. However, there are differences across jurisdictions on the definition of ‘red’, ‘amber’ and ‘green’ products, and the portion sizes allowable for different F&B categories (See Appendix B, available from: figshare.com/s/82395ca5b89253d98822).

NSW is the only jurisdiction that classifies F&B into ‘everyday’ and ‘occasional’ items and employs the Health Star Rating (HSR) system22 to evaluate the nutrient content of packaged products, with products receiving an HSR ≥ 3.5 deemed to be healthier choices.

Australian healthy food retail policies implementation designs

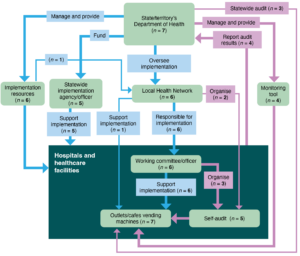

The common elements of the Australian healthy hospital retail policies implementation design are presented in Figure 1. Details of the implementation process for each jurisdiction are presented in Appendix C (available from: figshare.com/s/82395ca5b89253d98822). All jurisdictions provide policy guidelines but devolve the responsibility of implementation, monitoring and compliance audit of the policies to local health networks (LHN), which are legal entities established by Australian state/territory governments to decentralise operational management of public hospitals.23 Different jurisdictions use different terms to refer to these entities, such as primary health networks (Queensland), health service providers (WA), or local health districts (NSW). In this context, LHNs are responsible for ongoing policy implementation, monitoring and compliance audits in all jurisdictions, except Victoria, where each hospital is responsible for implementation.

Figure 1. Implementation diagram of the healthy hospital retail policies (click figure to enlarge)

Notes: Light green boxes: common implementation component/stakeholder. Thick blue arrows: common implementation step(s). Thin blue arrows: variations in the implementation step(s). Thick pink/purple arrows: common monitor/audit step(s). Thin pink/purple arrows: variations in the monitor/audit step(s).

n = number of states/territories

All jurisdictions provide promotional resources and support LHNs/hospitals to implement the healthy hospital retail policy. These resources differ in their design and detail but include recipe ideas, support websites, posters, and email support. Five jurisdictions (ACT, NT, Queensland, SA, Victoria) have a statewide implementation support agency/officer that can guide implementation staff. Five jurisdictions (Victoria, Queensland, SA, NSW, WA) provide menu assessment tools for retailers. Three (Victoria, Queensland, SA) employ the same menu assessment tool, FoodChecker – developed by Nutrition Australia’s Victoria Division, with funding from the Victorian Government.24 NSW uses the Population Health Intervention Management System (PHIMS).25 WA provides retailers with a Microsoft Excel tool to guide F&B nutritional classification.26 A working committee/officer role is established in hospitals in many jurisdictions (Queensland, NSW, SA, NT, Victoria, ACT) to ensure effective policy implementation. The committee often includes a combination of hospital managers, board members, health professionals such as dietitians who assist retailers with implementation and compliance audits, retail contract managers and retailers.

Policy compliance is the extent to which food outlets, vending machines and catering services adhere to the required standards for the availability and promotion of F&B offered within hospitals. Full compliance is defined as all F&B providers within a hospital setting fulfilling all policy requirements.19,20 All jurisdictions except NT have audit mechanisms in place. WA does not require hospitals to share these results with the Department of Health, while audit feedback requirements in SA and ACT are unclear.13,15 Four jurisdictions have published compliance audit results (SA, WA, Queensland and Victoria).17-20 In Queensland, 78% of facilities reported compliance with more than half the policy requirements and 25% reported full compliance in 2009.17 Compliance in SA was approximately 76% for retail outlets and vending machines in 2011.18 WA reported approximately 51% compliance across 25 health facilities audited in 2018–19.20 Victoria reported 88% of health services achieving phase 1 policy compliance in 2022.19 No jurisdictions have published policy effectiveness findings on purchasing behaviours.

Effectiveness of hospital healthy food retail interventions

The scoping review identified 27 studies that evaluated the effectiveness of health-promoting F&B retail interventions/policies in hospital settings. Study details are reported in Appendix D and E (available from: figshare.com/s/82395ca5b89253d98822).

Healthy hospital retail policies that are similar to the Australian policies

Twenty of the 27 included studies were considered relevant to the Australian policy context as the intervention component(s) examined in these studies were comparable to components of the Australian policies, such as limiting the availability of ‘red’ food to 20% and increasing the availability of ‘green’ food to at least 50%, or removal of ‘red’ beverages (Appendix E, available from: figshare.com/s/82395ca5b89253d98822). Evidence from the literature related to regulating the availability standards of healthy food is presented, followed by evidence regarding regulating standards around the availability of healthy beverages.

Studies limiting ‘red’ and increasing ‘green’ food products

Two qualitative studies and two mixed-method studies examined the intervention impacts of limiting ‘red’ food options to 20% and increasing ‘green’ food options to 50% of available food products. They found an increase in the promotion of fruit and sales of ‘green’ food. Results reported a decrease in the number of chocolates on display; energy per food package; total fat, saturated fat, and sugar per 100 g of food sold; and sales of ‘red’ and ‘amber’ food. Two studies reported revenue impacts on retailers, with one study reporting an increase in revenue while the other showed a decrease. Results of these studies are relevant to all Australian jurisdictions, except NSW given that NSW has a policy around ‘everyday’ and ‘occasional’ beverages availability.

Studies limiting ‘occasional’ or unhealthy foods and increasing ‘everyday’ or healthy food

One mixed-method study investigated interventions limiting the availability of unhealthy food options to 25% while increasing the availability of healthy options to 75%. An additional quantitative study examined the impacts of varying the availability of healthy options (25% versus 75%). The first study reported an increase in the proportion of ‘green’ foods sold. The second study reported that participants were 2.9 times more likely to select healthy options when they constituted ≥ 75% of the available choices, resulting in increased sales of healthy food options. The results of these studies are potentially applicable to NSW which has a policy around ‘occasional’ and ‘everyday’ food availability.

Studies increasing ‘green’ beverages

Four studies examined interventions that increased ‘green’ beverage options availability to 50% or increased ‘amber’ and ‘green’ options to 80% of all available beverages. Two studies were mixed-method, one was quantitative, and one was qualitative. Results showed an increase in the proportion of ‘green’ beverages sold and a decrease in the proportion of ‘amber’ beverages sold, the volume of ‘red’ beverages sold, and the total sugar content sold. Two studies reported mixed results related to sales revenue, with one recording a reduction in sales revenue and one reporting no change. Results of these studies are relevant to all jurisdictions, except NSW given that NSW has a policy around ‘everyday’ and ‘occasional’ beverages availability.

Studies removing ‘red’ beverages from sales

Three mixed-method studies and one quantitative study examined interventions that removed ‘red’ beverages from sales (Appendix E, available from: figshare.com/s/82395ca5b89253d98822). These studies reported an increase in the proportion of ‘green’ items sold. There were inconclusive results related to the proportion of ‘amber’ items sold. The results of these studies are relevant to all jurisdictions.

Studies combining increased availability of healthy F&B, decreased availability of unhealthy F&B and nutrition labelling

Eight quantitative studies examined interventions that paired increased healthy F&B availability with nutritional labelling to alert customers to the healthiness of F&B options. Studies reported an increase in the proportion of vending machines that labelled healthier beverages and the proportion of ‘green’ options sold, and a decrease in the proportion of ‘red’ options sold, the proportion of energy from fat in products sold, and in the total energy in F&B sold. One study showed additional reductions in the proportion of ‘red’ beverages sold when the intervention included both nutrition labelling, increased visibility and accessibility of ‘green’ beverages, and decreased visibility and accessibility of ‘red’ beverages compared to nutrition labelling alone. Although all Australian policies aim to increase the availability of healthy F&B, no policies include a labelling component and therefore it is unclear whether these studies could inform the effectiveness of the Australian policies.

Facilitators and barriers to implementation

Various factors influencing the implementation of hospital healthy retail interventions were reported in seven mixed-method studies and two qualitative studies. These factors included intervention acceptability and support from all stakeholders including hospital management, retailers, staff and visitors; practical supporting resources to understand and implement the intervention requirements; impacts on retailer profitability; the ability of retailers to navigate conflicting demands between policy compliance, customer satisfaction and profitability; a range of healthy options provided by suppliers; and continuous monitoring of the impacts of the intervention on purchasing behaviours of staff and visitors.

Healthy hospital retail policies that differ from the Australian hospital retail policies

Nine studies examined interventions with component(s) that were different to the Australian hospital retail policies, such as increased ‘red’ beverage prices; prompts to promote healthier F&B options; and labelling (e.g., traffic light, or step equivalent). Six studies were quantitative, and one was a mixed-method study.

One multicomponent study increased prices of sugary beverages, reduced bottled water prices and implemented traffic light nutrition labelling and health messaging. Results showed that traffic light labelling resulted in a higher proportion of healthier F&B being purchased compared to increased sugary beverage prices and reduced bottled water prices. The addition of caloric information to traffic light labelling further increased the proportion of healthier chips purchased.

Three studies included prompts and health messaging, such as prompts to reduce salt intake or choose healthier snacks. While two studies found the interventions had no impacts on healthy food choices, one reported small but statistically significant reductions in the energy content of snacks purchased.

One study that labelled healthier meals showed a reduction in fat, salt and refined sugar purchased. Two studies investigated the impacts of F&B placement prominence – one study focused on meals and one on desserts. They found that the placement prominence of healthier food options had no impact on consumer choices of these options.

One mixed-method study examined an intervention that increased the prices of ‘red’ beverages and reported a decrease in the volume of ‘red’ beverages sold, the proportion of calories and sugar sold, and an increase in the volume of ‘green’ beverages sold. Beverage revenue was reduced; however, food revenue was unimpacted. There was low intervention acceptability among customers.

Discussion

Healthy hospital retail policies are designed to ensure that healthier F&B are sold within public healthcare settings, which helps reinforce these settings as places that support the health and wellbeing of staff and visitors. This study sought to analyse the details of the Australian healthy hospital retail policies and their potential impacts on dietary behaviours. Audits have shown that these policies have the potential to positively impact the food retail environment by reducing the availability of unhealthy products and increasing the availability of healthy products.17-20 However, the Australian policies have not been evaluated for effectiveness, therefore a review of the published literature was used to provide evidence about their potential effectiveness. Studies show that if implemented effectively, Australian policies are likely to increase healthier F&B purchases.

State- and territory-based policy development and implementation is resource-intensive.27 The similarities shared across jurisdictions related to policy components and implementation designs – such as the use of the ADG and the traffic light system to determine the availability standards of F&B for sales – allow for inter-jurisdictional collaboration and the sharing of resources and learnings. For example, the FoodChecker tool, developed by Nutrition Australia’s Victorian Division, with funding from the Victorian Government, to assess F&B nutritional profile9,24, has been adopted by Queensland and SA to support the implementation of their policies.10,13 Additional opportunities for resource sharing exist, for example, rather than using state-based implementation support agencies, a single body could provide this service for all jurisdictions. This would require greater alignment of policy details related to the criteria used to classify healthy and unhealthy F&B.

The impacts of these policies hinge on effective and successful implementation. Various factors impact successful implementation. These include: 1) strong policy support from all stakeholders; 2) practical implementation support resources; and 3) impacts on retailers’ profitability. Current healthy hospital retail policies have considered many of these factors, such as the provision of implementation resources to communicate the policy requirements to hospital settings and engage staff and visitors with the policies, or the monitoring mechanisms in some jurisdictions. However, other factors require further consideration to ensure the effective implementation of the policies over time. These include the ability of retailers to navigate conflicting demands between policy compliance, customer satisfaction and profitability; and the range of healthier F&B options available from suppliers. In addition to providing jurisdiction-specific lists of compliant suppliers and products, further alignment of policies across jurisdictions could incentivise national food manufacturers to develop products that are compliant with standards across all jurisdictions. Furthermore, the assessment of policy impacts on retailer profits and purchasing behaviours of staff and visitors should be incorporated into the current policy compliance monitoring mechanisms to allow a comprehensive understanding of policy impacts on all stakeholders. Jurisdictions may have collected these data; however, the lack of publicly available data limits the comprehensive assessment of policy impacts, and the ability of other Australian and international jurisdictions to learn from the Australian experience.

There is evidence showing that several retail interventions have positive impacts on the purchasing behaviours of staff and visitors, and these should be considered for inclusion in current Australian policies. Nutritional labelling to alert customers to the healthiness of F&B options, such as calorie labelling, or traffic-light labelling, increased healthier F&B purchases by staff and visitors. Similarly, increasing prices of ‘red’ beverages showed a decrease in the purchase of ‘red’ beverages and an increase in the purchase of ‘green’ beverages, although customer support for this policy component is likely limited.

This study represents the first comprehensive analysis of the Australian healthy hospital retail policies and their potential impacts on the dietary behaviours of staff and visitors. While this study focused on the Australian policies within hospital settings, these findings might also be relevant to large non-healthcare workplaces, or other settings with access to on-site food outlets and vending machines, such as schools and universities.28

Limitations

The study has several limitations. Firstly, despite being invited, some jurisdictions were not represented in the project stakeholder group and therefore details for four jurisdictions were based solely on publicly available information. Furthermore, the focused aim of the scoping review may have resulted in the omission of other relevant studies, such as retail food environment interventions in workplaces in general.29-31

Conclusion

All Australian jurisdictions except Tasmania have implemented healthy hospital retail policies. Several similarities exist regarding policy design and implementation processes, allowing an opportunity for inter-jurisdictional collaboration and resource sharing. However, further alignment of policies and policy evaluation will allow for increased efficiency and refinement to ensure effectiveness. The literature indicates that these policies have the potential to improve dietary behaviours among hospital staff and visitors.

Acknowledgements

HT and JA are researchers with the National Health and Medical Research Council funded Centre of Research Excellence in Food Retail Environment for Health (REFRESH) (GNT1152968). JA is supported by a Deakin University Postdoctoral fellowship and reports funding from The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre to attend the Australian Health Economics Society conference. NW is funded by an NHMRC Ideas Grant (GNT2002234). NW has a scholarship through Deakin University Postgraduate Research Scholarship. SK is funded by the Deakin Health Economics Internship Program.

We would like to acknowledge Siti Khadijah Binti Mohamad Asfia for their valuable assistance in data collection and data extraction.

The opinion, analysis and conclusions presented in this paper are solely of the authors and should not be attributed to any funding bodies.

This paper is part of a special issue of the journal focusing on: ‘Collaborative partnerships for prevention: health determinants, systems and impact’. The issue has been produced in partnership with the Collaboration for Enhanced Research Impact (CERI), a joint initiative between The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre and NHMRC Centres of Research Excellence. The Prevention Centre is managed by the Sax Institute in collaboration with its funding partners.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, invited.

Copyright:

© 2024 Tran et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Australian Institute of Health Welfare. Diet. Canberra: AIHW; 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 5]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/food-nutrition/diet

- 2. Leng G, Adan RAH, Belot M, Brunstrom JM, de Graaf K, Dickson SL, et al. The determinants of food choice. Pro Nutr Soc. 2017;76(3):316–27. CrossRef | PubMed

- 3. Pitt E, Gallegos D, Comans T, Cameron C, Thornton L. Exploring the influence of local food environments on food behaviours: a systematic review of qualitative literature. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(13):2393-405. CrossRef | PubMed

- 4. Swinburn B, Sacks G, Vandevijvere S, Kumanyika S, Lobstein T, Neal B, et al. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): overview and key principles. Obes Rev. 2013;14 Suppl 1:1–12. CrossRef | PubMed

- 5. Needham C, Orellana L, Allender S, Sacks G, Blake MR, Strugnell C. Food retail environments in Greater Melbourne 2008–2016: longitudinal analysis of intra-city variation in density and healthiness of food outlets. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1321. CrossRef | PubMed

- 6. Bell C, Pond N, Davies L, Francis JL, Campbell E, Wiggers J. Healthier choices in an Australian health service: a pre-post audit of an intervention to improve the nutritional value of foods and drinks in vending machines and food outlets. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:492. CrossRef | PubMed

- 7. Dawson J. Retailer activity in shaping food choice. Food Quality and Preference. 2013;28(1):339–47. CrossRef

- 8. Utter J, McCray S, Denny S. Work site food purchases among healthcare staff: relationship with healthy eating and opportunities for intervention. Nutri Diet. 2022;79(2):265–71. CrossRef | PubMed

- 9. Victorian Department of Health. Healthy choices: policy directive for Victorian public health services. Victoria: Victorian Government; 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 5]. Available from: www.health.vic.gov.au/publications/healthy-choices-policy-directive-and-guidelines-for-health-services

- 10. Health and Wellbeing Queensland. A better choice: food and drink supply strategy for Queensland healthcare facilities. Queensland: Queensland Government; 2022 [cited 2024 Mar 5]. Available from: hw.qld.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/A-Better-Choice-Strategy-for-Healthcare.pdf

- 11. Victorian Department of Health. Healthy and high-quality food in public hospitals and aged care facilities. Victoria: Victorian Government; 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 5]. Available from: www.health.vic.gov.au/quality-safety-service/healthy-and-high-quality-food-in-public-hospitals-and-aged-care-facilities

- 12. Department of Health WA. Healthy Options WA food and nutrition policy. Perth: Government of Western Australia; 2022 [cited 2024 Mar 5]. Available from: www.health.wa.gov.au/About-us/Policy-frameworks/Public-Health/Mandatory-requirements/Chronic-Disease-Prevention-and-Health-Promotion/Healthy-Options-WA-Food-and-Nutrition-Policy

- 13. SA Health. Healthy food and drink policy. Adelaide: Government of South Australia; 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 5]. Available from: www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/about+us/governance/policy+governance/policies/healthy+food+and+drink+policy

- 14. Northern Territory Government. Policy. Healthy food and drink options for staff, volunteers and visitors, in NT Health facilities. Darwin: NT Government; 2017 [cited 2024 Mar 5]. Available from: digitallibrary.health.nt.gov.au/prodjspui/bitstream/10137/904/3/Healthy%20Food%20and%20Drink%20Options%20for%20Staff%2C%20Volunteers%20and%20Visitors%20in%20NT%20Health%20Facilities%20Policy.pdf

- 15. ACT Health. Healthy food and drink choices policy. Canberra: ACT Government; 2018 [cited 2024 Mar 5]. Available from: www.health.act.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-02/Healthy%20Food%20and%20Drink%20Choices.docx

- 16. NSW Ministry of Health. Healthy Food and Drink in NSW Health facilities for staff and visitors framework. Sydney: NSW Government; 2017 [cited 2024 Mar 5]. Available from: www.health.nsw.gov.au/heal/Publications/hfd-framework.pdf

- 17. Miller J, Lee A, Obersky N, Edwards R. Implementation of a better choice healthy food and drink supply strategy for staff and visitors in government-owned health facilities in Queensland, Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(9):1602–9. CrossRef | PubMed

- 18. Berry N, Ward C. Evaluation site self-reporting conducted December 2011– February 2012: summary report of findings. In: SA Health, Health Promotion Branch; 2012 [cited 2023 Oct 25]. Available from authors.

- 19. Victorian Department of Health. Healthy choices: policy directive for Victorian public health services – Short summary – 2022 results. Victoria: Victorian Government; 2022 [cited 2024 Mar 5]. Available from: www.health.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-05/healthy-choices-policy-directive-for-victorian-public-health-services-%E2%80%93-short-summary-%E2%80%93-2022-r.pdf

- 20. Chronic Disease Prevention Directorate (Obesity Prevention). Healthy options WA: food and nutrition policy for WA Health services and facilities. 2018–19 statewide audit of policy implementation. WA: Government of Western Australia; 2020 [cited 2024 Mar 5]. Available from: www.health.wa.gov.au/~/media/Files/Corporate/Reports-and-publications/Audit-of-food-and-drink/2018-2019-Healthy-Options-WA-Policy-Statewide-Audit-of-Policy-Implementation-Report.pdf

- 21. National Health and Medical Research Council (2013) Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council [cited 2023 Oct 25]. Available from: www.eatforhealth.gov.au/guidelines/guidelines

- 22. Australian Government. Health Star Rating. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 25]. Available from: www.healthstarrating.gov.au/internet/healthstarrating/publishing.nsf/content/home

- 23. Australian Institute of Health Welfare. Local hospital network. Identifying and definitional attributes. Canberra: AIHW; 2019 [cited 2023 Oct 25]. Available from: meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/491016

- 24. Nutrition Australia Victorian Division. FoodChecker. Victoria: Victorian State Government; 2016 [cited 2024 Mar 5]. Available from: foodchecker.au

- 25. Green AM, Innes-Hughes C, Rissel C, Mitchell J, Milat AJ, Williams M, et al. Codesign of the population health information management system to measure reach and practice change of childhood obesity programs. Public Health Res Pract. 2018;28(3):e2831822. CrossRef | PubMed

- 26. Department of Health WA. Making healthy choices easier: how to classify food and drinks guide. WA Department of Health [Excel document]. Healthy Options WA Policy. WA: Government of Western Australia; 2020 [cited 2024 Mar 5]. Available from: www.health.wa.gov.au/Articles/A_E/About-the-Healthy-Options-WA-Policy

- 27. Walker JL, Littlewood R, Rogany A, Capra S. Implementation of the ‘Healthier Drinks at Healthcare Facilities’ strategy at a major tertiary children's hospital in Brisbane, Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2020;44(4):295–300. CrossRef | PubMed

- 28. van Trijp HC, Otten K, van Kleef E. Healthy snacks at the checkout counter: a lab and field study on the impact of shelf arrangement and assortment structure on consumer choices. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1072. CrossRef | PubMed

- 29. Naicker A, Shrestha A, Joshi C, Willett W, Spiegelman D. Workplace cafeteria and other multicomponent interventions to promote healthy eating among adults: a systematic review. Prev Med Rep. 2021;22:101333. CrossRef | PubMed

- 30. Lena A-K, Olalekan AU, Rosemary W, Samantha J, Oyinlola O. Choice architecture interventions to improve diet and/or dietary behaviour by healthcare staff in high-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e023687. CrossRef | PubMed

- 31. An R, Shi Y, Shen J, Bullard T, Liu G, Yang Q, et al. Effect of front-of-package nutrition labelling on food purchases: a systematic review. Public Health. 2021;191:59–67. CrossRef | PubMed