Abstract

Objective: To investigate the availability of resources at an Australian university workplace to support the health, wellbeing, and transition to parenthood of female employees working during the preconception, pregnancy, and postpartum periods.

Type of program or service: Workplace health promotion for female employees of reproductive age.

Methods: A survey of female employees aged 18–45 years evaluated participant health practices, availability of work and parenting supports, and access to health and wellbeing resources in the workplace. Additionally, an environmental assessment was completed by employees with a knowledge of local healthy lifestyle supports and a minimum of 2 years’ employment. The assessment documented site characteristics and availability of wellbeing facilities across 10 campuses.

Results: There were 241 valid survey responses. Of 221 respondents to a question about workplace support, 76% (n = 168) indicated that the workplace should play a role in supporting the transition to parenthood and in health promotion, with 64.1% of 223 participants disagreeing with the statement “my health is not the responsibility of the university”. Both the survey and environmental assessment revealed that access to parenting resources to support employee health and wellbeing were suboptimal.

Lessons learnt: There is a misalignment between the needs of female employees working during these health-defining life stages, and the availability of resources to support those needs. Regulatory guidance may be required to navigate resource gaps within the work environment and address factors impacting the health and wellbeing of employees of reproductive age.

Full text

Introduction

Workplaces are well positioned to support the wellbeing of preconception, pregnant, and postpartum (PPP) working women1, as 75% of Australian women of reproductive age are in the workforce.2 Further, employers have a duty of care to the health and safety of their employees.3 Workplace wellbeing programs for women often seek to improve individuals’ health behaviours4 and the physical and social environment can play an important role in preventive health by making “healthy choices easy choices” and providing individuals with greater control over factors impacting their health.5 Availability of family-friendly supports (for example, flexible working arrangements) has been associated with reduced parenting stress.6 Conversely, negative perceptions of workplace family support have been associated with poor physical health, depression and increased absenteeism.7 Additionally, working conditions (for example, psychosocial factors) may affect preconception health practices, pregnancy-related conditions, fetal health and development, reproductive health, and pregnancy outcomes.8,9

Formative research to develop a holistic workplace program to promote the wellbeing and health practices of PPP women at the University of Tasmania, Australia, indicated dissatisfaction with the availability of parenting supports and a lack of policy focus on overall wellbeing.8 Therefore, to explore the potential points of intervention at an environmental level, we conducted a survey and environmental assessment to investigate the availability and access to health and wellbeing resources for women working across the reproductive years at a university workplace.

Methods

We conducted a 67-question cross-sectional Work and Wellbeing Survey (See Supplement S1, available from: figshare.com/s/d4d0268f637983aab6b6h) at the University of Tasmania in November 2018. To facilitate recruitment, the survey was emailed once to all female staff aged 18–45 years (2599; 37% total staff), by the university’s People and Wellbeing (human resources) team, and was advertised in staff newsletters. The survey aimed to capture data on women’s wellbeing needs and access to resources, and included items relating to general health, exercise and fitness, diet, sleep and stress, workplace (organisation), work and parenting.

We also conducted an environmental assessment using a modified 53-question Environmental Assessment Tool (EAT; Supplement S2, available from: figshare.com/s/d4d0268f637983aab6b6) adapted from DeJoy et al.10 Modifications to the original EAT included units of measurement (imperial to metric), employee demographics (e.g., ethnicity), and inclusion of supports specific to the PPP years (e.g., breastmilk storage facilities). Female employees with a knowledge of local facilities and programs that promoted wellbeing (as indicated in recruitment material), and a minimum 2 years’ employment were recruited from university campuses with 10 or more female staff (aged 18–45 years). Participants were recruited to complete the EAT through department newsletters, the staff portal and emails sent to the executive assistants of senior employees. The EAT was completed by 10 participants across 10 university campuses (small to large campuses located across four distinct regions in Tasmania and Sydney; Supplement S3 for scale, available from: figshare.com/s/d4d0268f637983aab6b6) between November 2020 and April 2021. At one campus where there was more than one volunteer, the first to respond was selected to complete the survey.

Data were collected using REDCap11 and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25.0) and RStudio (version 4.2.2). This study was approved by the University of Tasmania Human Research Ethics Committee (H0017313 and H0022986). All participants provided informed consent.

Results

Survey results

There were 241 valid responses to the Work and Wellbeing survey (9% response rate), with more than 80% of respondents aged 32–45 years old (Table 1). Half were caring for children and 70 respondents (29%) planned to start or add to their family in the next 2 years. The median participant BMI was in the ‘normal’ range (24.4 kg/m2), however 76% wanted to weigh less. The median sitting time of respondents was considerably higher at work (85% time), compared with away from the university (30% time). Most respondents disagreed (‘disagree’ or ‘strongly disagree’) with the statement “my health is not the responsibility of the university”(n = 143, 64%) and the majority (n = 168, 76%) felt the workplace had a role in supporting the transition to parenthood. Access to supports for PPP employees (e.g., parenting facilities or flexible working arrangements) was not universally available. Access to general amenities (e.g., shower and changing facilities) varied among respondents (Supplement S4, available from: figshare.com/s/d4d0268f637983aab6b6).

Table 1. Description of survey respondents (N = 241)a

| Characteristic | Survey respondents, n (%) |

| Demographic information | |

| Age group (years) (n = 241) | |

| 18–24 | 10 (4.1) |

| 25–31 | 36 (14.9) |

| 32–38 | 100 (41.5) |

| 39–45 | 95 (39.4) |

| Education level (n = 241) | |

| Year 12 or below | 15 (6.2) |

| Certificate level | 11 (4.6) |

| Diploma | 12 (5.0) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 65 (27.0) |

| Higher university degree | 138 (57.3) |

| Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (n = 240) | |

| Yes | 3 (1.3) |

| No | 237 (98.8) |

| Employment status (n = 241) | |

| Ongoing | 129 (53.5) |

| Fixed term | 85 (35.3) |

| Casual | 27 (11.2) |

| Employment classification levelb (n = 240) | |

| Academic A–C | 53 (22.1) |

| Academic D–E | 1 (0.4) |

| HEO 1–4 | 27 (11.3) |

| HEO 5–6 | 75 (31.3) |

| HEO 7+ | 59 (24.6) |

| Not applicable | 25 (10.4) |

| Caring for children (n = 240) | |

| Yes | 126 (52.5) |

| No | 114 (47.5) |

| Number of children (n = 126) | |

| 1 | 46 (36.5) |

| 2 | 62 (49.2) |

| 3 | 15 (11.9) |

| 4 | 3 (2.4) |

| Planning to start or add to family in next 2 years (n = 239) | |

| Yes | 70 (29.3) |

| No | 169 (70.7) |

| Weight, health practices and wellbeing | |

| BMIc (n = 227) | Median kg/m2 (range) |

| 24.4 (17.9–48.3) | |

| Weight preference (n = 241) | n (%) |

| Happy as I am | 55 (22.8) |

| 1–5 kg more | 2 (0.8) |

| 1–5 kg less | 86 (35.7) |

| 6–10 kg less | 50 (20.7) |

| More than 10 kg less | 48 (19.9) |

| Percentage of time spent sitting (n = 234) | Median % time (range) |

| At the university | 85 (3–99) |

| Away from the university | 30 (2–90) |

| Fitness rating, 1 = lowest rating, 10 = highest rating (n = 231) | n (%) |

| 1–5 | 71 (30.7) |

| 6–10 | 160 (69.3) |

| Diet rating, 1 = lowest rating, 10 = highest rating (n = 230) | n (%) |

| 1–5 | 41 (17.8) |

| 6–10 | 189 (82.2) |

| Frequency of stress (n = 192) | n (%) |

| Rarely or sometimes | 118 (61.5) |

| Often or very often | 69 (35.9) |

| Always | 5 (2.6) |

| Response to questions/statements | |

| Does the workplace have a role in supporting the transition to parenthood? (n = 221) | n (%) |

| Yes | 168 (76) |

| No | 53 (24) |

| My health is not the responsibility of the university (n = 223) | n (%) |

| ‘Agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ | 80 (35.9) |

| ‘Disagree’ or ‘strongly disagree’ | 143 (64.1) |

| I am too busy with work to participate [in workplace wellbeing] activities (n = 222) | N = 222 (%) |

| ‘Agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ | 152 (68.5) |

| ‘Disagree’ or ‘strongly disagree’ | 70 (31.5) |

Data source: University of Tasmania Work and Wellbeing Survey, 2018.

a Variable n according to total number of responses.

b Academic A–C = Lecturer to Senior Lecturer (sometimes also Assistant Professor); Academic D–E = Associate Professor to Professor; HEO 1–7+ = Higher Education Officer, professional employees of increasing skill, expertise and experience level.

c Outliers excluded based on data cleaning procedures from Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health12: Weight > 139.9 kg; height > 200 cm and < 120 cm

Environmental assessment results

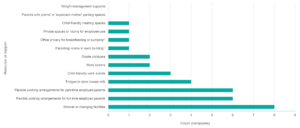

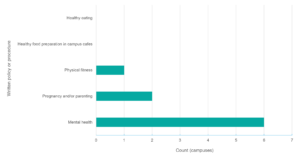

The EAT found that there was access to shower or changing facilities (n = 8, Figure 1) at most campuses, however few provided lockers (n = 2). Parenting amenities (for example, childcare) were unavailable at most worksites. Access to flexible work arrangements (a university-wide policy) varied according to work role, workload, manager and available cover. Respondents indicated that policies or procedures were in place to support employee mental health at more than half the campuses (n = 6) but not to support physical fitness, healthy eating, or pregnancy or parenting (Figure 2). Availability of resources to support fitness (e.g., walking paths, staff physical activity challenges, gym resources) and healthy eating (e.g., onsite cafes) varied across campuses. Vending machine images provided by participants demonstrated ease of access to discretionary foods (See Supplement S3, available from: figshare.com/s/d4d0268f637983aab6b6).

Figure 1. Campus characteristics, facilities, and programs to support wellbeing from the environmental assessment (N = 10 campuses) (Click figure to enlarge)

Data source: Environmental assessment at University of Tasmania.

a n = 9.

b Under certain circumstances.

Figure 2. Campus policies to support wellbeing from the environmental assessment (N = 9 campuses)a (Click figure to enlarge)

Data source: Environmental assessment at University of Tasmania.

a One participant did not complete questions relating to current health promotion policies.

Discussion

To our knowledge, we are the first to assess access to wellbeing resources for PPP female employees in a workplace and, more specifically, within a higher education workplace setting. Survey participants indicated that the university plays a role in their health and supporting the transition to parenthood. However, awareness and/or availability of amenities to complement the health and wellbeing of employees across the PPP periods was variable or absent. This included physical amenities (for example, parenting rooms in each building) and written policies and procedures (for example, to support healthy eating).

In capturing the workplace wellbeing needs and expectations of PPP working women and variation in access to corresponding resources, this study highlighted the inequitable resource distribution for female employees of reproductive age. Embracing a future where workplaces actively seek to “protect, serve and promote health”13 should include monitoring for such inequities among subgroups of workers, as they may result in disproportionate impacts on health.14 Given the potential for far-reaching, intergenerational benefits to health1 and emerging evidence linking work to the health practices and wellbeing of PPP working women9, there is a compelling need to improve the work environment.

Limitations of this study included a low survey response rate (9%), and that the sample rated diet and fitness highly compared to national averages.15 This may be due to the use of self-reported data, the high education status of respondents, or nonresponse bias (leading to an underrepresentation of those with lower health status).16 Thus, caution is required when extending findings from this sample to the wider university population. The original EAT survey10 was designed to be undertaken by researchers, however the local knowledge of participants was valuable for overcoming previously identified gaps in wellbeing provision (e.g., uncoordinated or unsustained advertising of wellbeing activities).8 Our EAT was conducted during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, across a 6-month time frame. Therefore, there may have been some variability in resource availability, as many activities are organised around teaching semesters. This suggests that current supports may be targeted at students, rather than staff.

Application of this work

While the current findings will contribute to the development of a place-based workplace program, there is a need to address work processes and structural inequities in the higher education settings internationally, as demonstrated in the US and UK.17,18 This can range from the decreased representation of women holding higher-level academic positions19 to the nature of academic work, which results in work intensification and adversely affects employees’ work-life-family balance.20 The breadth of such inequities may be clarified by applying an environmental assessment, and subsequently modifying inherent biases and impacts on health and wellbeing at an organisational level.

Conclusion

There are deficiencies in the working environment to support general employee health and, especially, that of employees in the preconception, pregnancy and postpartum years. Growing awareness of the pathways between work and health suggests that such deficiencies may have tangible impacts on PPP working women.9 Caution is required in generalising the current findings, however regulatory change may be required to elaborate on employers’ duty of care to address the pitfalls and inequities of the physical working environment for PPP female employees.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank Ms Emily Green for her assistance with manuscript administration tasks and Dr Cate Bailey for her guidance in refining the Work and Wellbeing Survey.

Funding for this research was provided by the Australian Government’s Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF; TABP-18-0001) and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) through the Centre for Research Excellence in Health in Preconception and Pregnancy (GNT1171142).

SM was funded by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Stipend and RTP Fee-Offset Scholarship. Funding for the creation and distribution of the Work and Wellbeing Survey was provided by People and Wellbeing at the University of Tasmania, Australia. AH and BH were funded by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (GNT 1120477) and Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE230100704). MRFF funding was provided to The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre under the MRFF Boosting Preventive Health Research Program.

This paper is part of a special issue of the journal focusing on: ‘Collaborative partnerships for prevention: health determinants, systems and impact’. The issue has been produced in partnership with the Collaboration for Enhanced Research Impact (CERI), a joint initiative between The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre and NHMRC Centres of Research Excellence. The Prevention Centre is managed by the Sax Institute in collaboration with its funding partners.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, invited.

Copyright:

© 2024 Madden et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Madden SK, Skouteris H, Bailey C, Hills AP, Ahuja KDK, Hill B. Women in the workplace: promoting healthy lifestyles and mitigating weight gain during the preconception, pregnancy, and postpartum periods. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):821. CrossRef | PubMed

- 2. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Labour force, Australia: changing female employment over time. Canberra: ABS; 2021 [cited 2023 Jan 27]. Available from: www.abs.gov.au/articles/changing-female-employment-over-time

- 3. Safe Work Australia. Model work health and safety regulations. Canberra: Parliamentary Counsel’s Committee; 2022 [cited 2023 Feb 9]. Available from: www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-06/model_whs_regulations_-_14_april_2022.pdf

- 4. Madden SK, Cordon EL, Bailey C, Skouteris H, Ahuja K, Hills AP, Hill B. The effect of workplace lifestyle programmes on diet, physical activity, and weight-related outcomes for working women: a systematic review using the TIDieR checklist. Obes Rev. 2020;21(10):e13027. CrossRef | PubMed

- 5. Koelen MA, Lindström B. Making healthy choices easy choices: the role of empowerment. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(1):S10–6. CrossRef | PubMed

- 6. Hwang W. The effects of family-friendly policies and workplace social support on parenting stress in employed mothers working nonstandard hours. J Soc Serv Res. 2019;45(5):659–72. CrossRef

- 7. Matias M, Ferreira T, Vieira J, Cadima J, Leal T, Mena Matos P. Workplace family support, parental satisfaction, and work–family conflict: individual and crossover effects among dual-earner couples. Appl Psychol. 2017;66(4):628–52. CrossRef

- 8. Madden SK, Blewitt CA, Ahuja KDK, Skouteris H, Bailey CM, Hills AP, Hill B. Workplace healthy lifestyle determinants and wellbeing needs across the preconception and pregnancy periods: a qualitative study informed by the COM-B model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4154. CrossRef | PubMed

- 9. Madden SK, Ahuja KDK, Blewitt C, Hill B, Hills AP, Skouteris H. Understanding the pathway between work and health outcomes for women during the preconception, pregnancy, and postpartum periods through the framing of maternal obesity. Obes Rev. 2023;24(12):e13637. CrossRef | PubMed

- 10. DeJoy DM, Wilson MG, Goetzel RZ, Ozminkowski RJ, Wang S, Baker KM, et al. Development of the Environmental Assessment Tool (EAT) to measure organizational physical and social support for worksite obesity prevention programs. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(2):126–37. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. Ball J, Ford J, Russell A, Williams L, Hockey R. Data cleaning for height and weight: Newcastle, NSW: ALSWH data dictionary supplement; 2009 [cited 2023 Jan 27]. Available from: alswh.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/DDSSection3Data-Cleaning-for-Height-and-Weight.pdf

- 13. Ghebreyesus TA [@DrTedros]. Half of the world’s population are working people: twitter.com/DrTedros/status/1728474901734883578. US: X; 26 November 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 17]. Available from: twitter.com/DrTedros/status/1728474901734883578

- 14. World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on mental health at work. Geneva: WHO; 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 1]. Available from: iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/363177/9789240053052-eng.pdf?sequence=1

- 15. Nichols M. Diet and physical activity in Australian adults. Victoria: Obesity Evidence Hub, Cancer Council; 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 2]. Available from: www.obesityevidencehub.org.au/collections/trends/adults-diet-exercise

- 16. Cheung KL, ten Klooster PM, Smit C, de Vries H, Pieterse ME. The impact of non-response bias due to sampling in public health studies: a comparison of voluntary versus mandatory recruitment in a Dutch national survey on adolescent health. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):276. CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. Morgan AU, Chaiyachati KH, Weissman GE, Liao JM. Eliminating gender-based bias in academic medicine: more than naming the "elephant in the room". J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(6):966–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 18. Davies J, Yarrow E, Syed J. The curious under-representation of women impact case leaders: can we disengender inequality regimes? Gend Work Organ. 2020;27(2):129–48. CrossRef

- 19. Curtis JW. The employment status of instructional staff members in higher education, Fall 2011. American Association of University Professors. 2014:2011–12. CrossRef

- 20. Hardy A, McDonald J, Guijt R, Leane E, Martin A, James A, et al. Academic parenting: work–family conflict and strategies across child age, disciplines and career level. Stud High Educ. 2018;43(4):625–43. CrossRef