Abstract

Objectives: Data presented in this paper were gathered during the Urban Hearing Pathways study. The objective of the study was to investigate how access to, and availability of, ear health and hearing services contributes to the burden of avoidable hearing loss experienced by young, urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and their families. The objective of this paper is to present the perspectives of parents and carers about awareness and concern in their community, detection and diagnosis of children’s ear health and hearing problems in primary care, and impacts of delays in diagnosis on children and families. These perspectives are complemented by those of health professionals.

Importance of study: The study findings address an evidence gap relating to factors that prompt an ear health and hearing check for young, urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. They reveal the difficulties families experience in establishing a diagnosis of chronic ear disease and receiving the care they perceive will effectively addresses their child’s needs.

Study type: Qualitative study with surveys.

Methods: The project team consisted of six Aboriginal researchers and 10 non-Indigenous researchers. Data collection tools and methods were designed by the project team. A total of 33 parents and carers completed surveys, and most also took part in interviews (n = 16) or focus groups (n = 16); 23 described their child’s ear health journey. Fifty-eight service providers from the health, early childhood and community service sectors completed anonymous surveys and 26 were interviewed. Descriptive statistics were generated from survey data and thematic analysis was conducted for interview and focus group data.

Results: Five main themes emerged from the analysis of parent and carer interviews: community knowledge and parent/carer recognition of signs of ear health and hearing problems; parent and carer action-taking; getting ear health and hearing checks; recognition of persistent problems; and impacts of delays on children and families.

Conclusions: Reiterating previous findings, there is no evidence of a systematic approach to ear checks for this at-risk population. A significant proportion of parents and carers are noticing problems by watching their child’s listening behaviours: early and reliable indicators of hearing status that can be harnessed. Some persistent ear health problems are being managed in primary care as acute episodes, thus delaying specialist referral and increasing developmental impacts on the child. Parents’ and carers’ practical recommendations for improving hearing health services are presented.

Full text

Introduction

Sometimes you think they’re being mugul. Sometimes they’re gammin, playing tricks, but sometimes it’s ears. Hard to tell the difference.

The Urban Hearing Pathways project (2019–20) sought to understand access to ear health and hearing services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and its role in reducing avoidable hearing loss in children younger than 6 years in urban areas of Australia. The project was established in response to ongoing concerns about access to services, raised at the community level.

Approximately 30% of urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children experience persistent middle ear infection or otitis media in early childhood.1-3 Although these ear health problems are often established within the first 2 years of life1,2, many children do not receive effective remediation of hearing impairment until 4–5 years of age.4,5 Because of the role of hearing in early language, cognitive and psychosocial development, timely access to ear health and hearing care is critical for mitigating developmental delay at school entry.6-8 Although Aboriginal families in urban settings might be expected to have easy access to ear health and hearing care, difficulties with access to health services are well documented.9-11 Literature specifically about access to ear and hearing services in urban areas is limited12,13, although several studies have provided and evaluated improved access to care while investigating hearing health service shortfalls.2,14,15 To help address this gap in the literature, this paper focuses on a segment of the hearing health journey that starts with parent, carer and community knowledge, and continues through to diagnosis in primary care of a persistent ear health problem. This is a critical point, at which risks to development and wellbeing increase, and referrals for specialist care are recommended.16

Methods

The Urban Hearing Pathways study adhered to principles of research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities. The project responded to concerns identified at the community level by both families and services. Extensive in-person consultation was undertaken in Australian urban areas with relevant Aboriginal community controlled and mainstream services and key individuals. Knowledge exchanged during these discussions informed the conduct of the project, including adhering to Aboriginal ways of working. The project ensured benefits to participating communities through provision of free, place-based ear health and hearing clinics, and to participating parents and carers through provision of gift cards to acknowledge the time and knowledge they shared. Three of the Aboriginal project team members were introduced to research work through the project; for two this has led to ongoing participation and employment in research. The project benefited from Aboriginal knowledge at all stages, including project design, data collection and interpretation, and development of recommendations.

Participant selection and recruitment

Participants were parents and carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged under 6 years and healthcare and community service providers living and/or working in the project locations. All locations are urban areas with significant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations: Midland, Western Australia (4%); Newcastle, New South Wales (3.7%); and Ipswich, Queensland (4.4%).17 Parents and carers were recruited using a snowball approach through the health, early childhood and community services which supported the project. Promotion was via word of mouth, including during participation in clinics provided by the project, and information posted at the centres. Service providers were invited to take part in surveys and interviews via emails shared internally by their service management. Ethics approvals were obtained from relevant ethics committees for the three locations (see Appendix 1, available from: https://osf.io/q6yx7).

Survey, interview and focus group design

The project team, which included Aboriginal project and research officers, used an iterative process to develop and refine the survey and interview tools. The questions in the surveys and interviews were designed to: 1) gain insights into parents’ and carers’ knowledge of ear and hearing health for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, relevant treatments and impacts, and their experience of the hearing health system; 2) map existing ear health and hearing services and pathways, and blockers and facilitators to accessing and progressing along the pathways (see details in Appendix 2, available from: https://osf.io/xckhp).

A short survey with six questions collected demographic characteristics about parents and carers and addressed the two aims mentioned above, using a combination of Likert scales and open-ended questions. More detailed information was collected through semi-structured interviews and a journey mapping activity. A longer survey collected demographic characteristics about service providers and addressed the two aims mentioned above. Four survey questions were the same for both parent/carer and service provider groups and the rest were tailored. More detailed information was collected through semi-structured individual interviews.

Data collection

Surveys were administered in person to parents and carers by the project team, and were completed online, anonymously, by health service providers.

Interviews were conducted with parents and carers by authors SM, NR, KC, GO, TM, TR and STH between March and October 2020, either in person in community settings or via videoconferencing if coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) restrictions necessitated. Social distancing requirements in force at the time meant that focus groups could only be carried out in Ipswich and Midland; in Newcastle, only one parent was involved per interview (single-participant interviews). Interview teams usually consisted of an Aboriginal and a non-Indigenous project team member, who also transcribed the interviews.

Participation was voluntary for the surveys and interviews. The project was explained, and informed consent obtained, before interviews began. Participants were advised they could withdraw consent at any time, and parents and carers were assured that this would not affect access to services provided through the project. Parents and carers received a gift card in appreciation of the time and knowledge they shared. Notes were read back to interviewees to check understanding and were de-identified by the interviewers before sharing for analysis. Interviews ended when no more new themes emerged.

Data analysis

An experienced qualitative researcher oversaw the conduct and analysis of the research. Descriptive statistics were computed on the quantitative data derived from the survey responses. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the qualitative data from the survey, interviews and focus groups. Each of the datasets were coded by two researchers and the codes were collated and reviewed to identify common themes. The whole team, including Aboriginal research and project officers, came together to discuss, interpret and refine the themes. All findings were derived from survey, interview and focus group data.

Results

Thirty-three parents and carers took part in the project; all completed the short survey. Thirty-two participants took part in interviews: 16 during individual interviews and 16 as part of small focus-group discussions. A total of 23 parents and carers recounted their child’s ear health journey. Fifty-eight service providers completed anonymous online surveys (72% health; 28% early childhood and community support) and 26 took part in interviews (58% health; 42% early childhood). Participant information most relevant to this paper is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary participant information for parents/carers (N = 33) and service providers (N = 58)

| Parent and carer surveys, interviews and journey maps | |||

| Conducted in single participant format (n) |

Conducted in small group format (n) |

Total respondents (n) |

|

| Surveys | |||

| Western Australia | 7 | 4 | 11 |

| NSW | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| Queensland | 0 | 12 | 12 |

| Total | 17 | 16 | 33 |

| Interviews | |||

| Western Australia | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| NSW | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| Queensland | 0 | 12 | 12 |

| Total | 16 | 16 | 32 |

| Journey maps | |||

| Western Australia | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| NSW | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| Queensland | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Total | 16 | 7 | 23 |

| Service provider surveys | |||

| Health providers (n) |

Education and community support (n) |

Total respondents (n) |

|

| Location | |||

| Western Australia | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| NSW | 21 | 2 | 23 |

| Queensland | 18 | 13 | 31 |

| Role typea | |||

| Direct care role | 20 | 9 | 29 |

| Managing role | 8 | 4 | 12 |

| Client support role | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Medical/surgical role | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| Clinical funding role | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Health provider type | |||

| Primary health | 19 | NA | NA |

| Hearing and ENT services | 8 | NA | NA |

| Other | 6 | NA | NA |

| Not stated | 9 | NA | NA |

| Total | 42 | 16 | 58 |

ENT = ear, nose and throat; NA = not applicable; NSW = New South Wales

a Some service providers had more than one role

The information below was predominantly drawn from the qualitative and quantitative information shared by parents and carers. In places, relevant information from the primary health surveys is drawn in. This paper focuses on the period starting with prevailing ear health and hearing awareness in the community, to the point of diagnosis in primary care of a persistent problem. Five key themes emerged from data.

Theme 1. Community knowledge and parent/carer recognition of a problem

Subtheme: ‘We need to let parents know the signs, tell them real early’

For both parents/carers and service providers in the three urban locations, ear and hearing troubles were a concern for children in their communities. In the surveys, a total of 75% of parents/carers and 85% of service providers either ‘strongly’ (42% and 55% respectively) or ‘somewhat’ (33% and 30% respectively) believed that this was the case. The qualitative data indicated parents and carers perceived there was a paucity of useful knowledge in the community among families who had not had direct experience of a child with a diagnosed ear health problem; and about indicators of ear and hearing problems and how to respond at the right moments in children’s lives:

The people that do talk about ears have had experience with ear trouble in their family, otherwise there’s nothing, just don’t know.

Parents and carers perceived there was not enough information available:

This needs to be brought in young, get in early, got to do this when the kids are really little. We need to let parents know the signs, tell them real early.

There was also a sense that new parents are a priority:

First time mums don’t know anything about ears. No, we really don’t know anything about ears.

Subtheme: ‘We want to know what we need to do’

In interviews, parents and carers were asked about actions they believed supported children’s ear health and hearing. A wide range of actions were cited; almost all are accepted as good practice (see Table 2). However, few related to primary prevention messages promoted by guidelines, such as keeping up with vaccinations, breastfeeding, hand and face washing, and not smoking around children.

Table 2. Parents and carers responses to: ‘What are some things you can do to help grow up your baby with healthy ears and good hearing?’

| Actions parents and carers cited as supportive of healthy ears and good hearing | Proportion who cited this |

| Get check-ups and hearing tests done | 34% |

| Go to the doctor or specialist | 34% |

| Don’t stick things in child’s ears | 25% |

| Clean/blow child’s nose | 19% |

| Clean child’s ears | 13% |

| Read to/engage baby to encourage hearing | 9% |

| Give child medicine | 6% |

| Encourage washing hands | 3% |

| No smoking around children | 3% |

Subtheme: ‘But what are ear signs? I am not sure’

A recurrent theme emerged around the difficulty parents and carers find in recognising an ear health problem themselves:

My boys didn’t really have any signs. No running ears. No big signs.

As one of the most common subtypes of otitis media presents without obvious signs or symptoms18, this is not unexpected. Several parents noted a tendency for signs that may relate to ear health being attributed to teething; and the difficulty working out whether certain listening behaviours may indicate a hearing problem – or not:

That’s the answer for tugging ears, other symptoms… everything is blamed on teething.

Sometimes you think they’re being mugul [stubborn or insolent]. Sometimes they’re gammin, playing tricks, but sometimes it’s ears. Hard to tell the difference.

Thematic analysis of parents’ and carers’ responses to ‘What might make you think your child has an ear health or hearing problem?’ suggest that children’s listening and communication behaviours are the most common indicators of a problem:

The child is frustrated when you are giving them directions. Child just sits and waits – they can’t pick up on everything you are saying…

Not responding how they should, (not) reacting to noises…

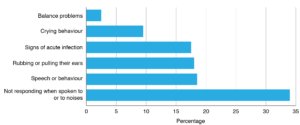

Participants cited ‘noticing speech problems’ and ‘noticing behaviour problems’ equally often, but these were not cited as frequently ‘ear rubbing’ and ‘acute signs of infection’. Crying behaviours and balance problems were least commented on as indicators (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Thematic analysis of parent and carer responses to ‘What might make you think your child has an ear health or hearing problem?’ (click to enlarge)

Theme 2: Taking action and feeling safe, welcome and understood

Sub theme: ‘Go to the GP’

In interviews, parents and carers almost universally said that if worried about their child’s ear health or hearing, their first step would be to see a general practitioner (GP). The role of Elders and Aunties in providing guidance was also acknowledged.

Sub theme: ‘Not having Aboriginal staff is a problem’

Unsolicited, parents and carers discussed health services where they felt – or did not feel – welcomed and understood, emphasising the close relationship between taking action and confidence in receiving safe and trusted care. Some parents indicated they travelled to services outside their area for this reason. Practices that employed Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander health staff were highly valued. Parents and carers also said it was possible to receive safe and welcoming care from non-Indigenous staff:

Not having Aboriginal staff is a problem; although I think you can relate to a non-Aboriginal doctor if they are good and understand.

Fear of interaction with child protection services was raised by parents and carers as an underlying worry for young parents that could hinder taking action:

Got to remember a lot of them have fear of (child protection services). They feel shame for no reason. They feel like they will get judged and they do.

Theme 3: Getting an ear and hearing check

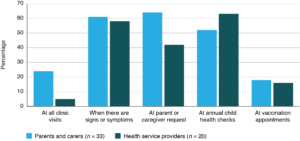

All parents, carers and health service providers were asked in the surveys about when health services check the ear health and hearing of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Respondents could choose more than one option and add additional answers. Responses aligned very closely between the two cohorts (see Figure 2). The most common responses for both groups were: ‘when there are signs or symptoms’, ‘as part of annual child health checks’ and ‘at parent/carer request’. Ear checks ‘at all clinic visits’ and ‘at immunisation appointments’ were least commonly selected.

Figure 2. Parent, carer and health service provider responses to ‘When do health services check ear health and hearing in children under 6 years?’ (click to enlarge)

Analysis of the ear health and hearing journey stories aligned with these findings. All the children whose journeys were shared had experienced persistent ear health and hearing problems. Only three journeys started with a routine check initiated by a health practitioner. For the remaining 20 children, the parent or carer initiated the ear check because of one or more concerns relating to visible signs, to their child’s response to sound, or to speech or behaviour problems.

Throughout interviews, parents and carers expressed frustration at the lack of routine checks for children known to be at risk of ear and hearing problems:

All doctors should know that our kids have ear susceptibility. Not sure mainstream surgeries know; they should look in kids’ ears every single time.

Theme 4: Primary health recognition of persistent ear health problems

A recurring theme emerged from qualitative data around parents and carers struggling to get ear health problems recognised as a persistent, ongoing condition rather than as a series of discrete episodes. Further, parents and carers struggled to obtain care that they felt effectively addressed the condition and/or its impacts; there was a sense of time passing with no resolution, and of resignation around not being heard:

Do we go back to the doctor again? Nope we don’t because they always say the same thing, it’s viral, it will go. Just give Nurofen and Panadol. So that’s what we keep doing. Over and over… Sometimes we go to another doctor because we know it’s still not right.

We do get our 715 health checks [Medicare Benefits Schedule Item 715 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Health Assessments]; why aren’t our kids’ ear problems being picked up? Every year my son has had a check. He’s had speech therapy because I knew his speech was behind… I’ve been over and over to doctors and they said it’s just viral… I got him checked when he was two and lots after that. Now he is 10 and we’re still waiting to see an ENT [ear, nose and throat specialist].

Theme 5: The impact of delays on children and families

Parents and carers shared the impacts on their child and family of waiting for care that would effectively address their ear health, hearing and communication problems; some mentioned the social impacts they see for their own child; and awareness of future risks for children associated with not hearing well during interactions with police:

The bad behaviours that come with the ear trouble affects everyone in family, everyone cops it, frustration from everyone. The physical hitting out at siblings out of frustration. Communication problems, can’t talk properly… All of this impacts.

His speech, he can’t get across what he wants to say, frustration. A lot of frustration for us all.

Child is an outcast because can’t hear. We see that.

…problems with ears can lead to problems like going to jail if we don’t deal with it. Police think kids are disrespectful or rude… A friend [aged] 15 can’t talk properly, hear properly, gets into trouble.

They also worry about the impacts of ineffectively addressed ear health and hearing problems for future generations:

We worry about our kids and the cycle. The intergenerational cycle needs to be broken. We need to help: teach us the signs, teach us early, teach us in schools, teach us when we are pregnant. Don’t assume we know: we don’t.

Parents and carers recommended improving cultural safety, health promotion and reach into communities. They shared practical recommendations for health services relating to: what culturally safe care should look and feel like; what and how hearing health information should be provided; and how services can improve reach into communities. Table 3 provides an overview of these recommendations.

Table 3. Overview of parents’ and carers’ recommendations for services

| Culturally safe services | |

| Should look like: | Should feel like: |

| “Welcoming staff, treated as an equal, nonjudgmental, friendly and wanting to know me and my family, can have some Aboriginal artwork, Aboriginal resources.” “Interested in what you’re saying, good rapport, helpful, value your time, patience with demanding children.” “Blame and shame free.” “Treated with kindness, don’t brush off concerns.” “No racism, greet with a smile and small talk.” |

“Feels safe when have good reception and staff that are accepting of changes and requests.” “Feels unreal, knowing that people care about you.” “Feels comfortable, inviting, safe, nonjudgmentWal, trusting.”“Feels trustworthy, feel accepted.” “Feel like you can ask any question.” “The staff feel like home, they make us feel welcome, they don’t talk down to anyone.” |

| Provision of hearing health information | |

| Should be about: | Should reach us: |

| “Don’t just say to us ‘do this’ – tell us how to do that and what it looks like.” “The signs.” “Milestones – when kids are meant to be doing things like talking.” “‘Is my child on track? I want to know how to keep them on track.” “What’s around re health services for our kids.” “Follow-up: what to do and where to go.” “Help us or tell us what we need to do while we wait to see the ENT.” “How to communicate with our kids who are part deaf.” |

“When we are teenagers; that would help us. Not just teach once but keep it going.” “When we are pregnant or before.” “While we wait to see the ENT.” “When we’re in high school.” “At schools, day cares, playgroups, mothers’ groups.” “‘Early: teach us in schools, teach us when we are pregnant. Don’t assume we know; we don’t.” |

| Improving reach into communities | |

| “Be out in the community, seeking community interest and advice, community days.” “Host informal, inviting sessions such as morning teas where parents can bring their children, the children can play and they can be informally screened for hearing concerns and the parents informed about ear disease and hearing loss.” “Don’t make promises you can’t keep.” “(Be) visually obvious around where the families gather. Can’t rely just on GPs to refer people to those services. Need to empower families to know about and detect ear problems so they can do something about it.” “Make sure services are consistent.” “Go to where the children are – schools, baby centres, hospitals. You need to be flexible. If you go and just set up a clinic somewhere without connections to children it is unlikely to be successful.’” “Cool t-shirts, forward liaison officer, someone who can talk to the community and the community can talk to them.” “Don’t just let people go there and leave, help us more than you should. Go above and beyond.” |

|

ENT = ear, nose and throat specialist; GP = general practitioner

Discussion

In summary, the findings reveal an unmet need for ear health and hearing promotion that effectively reaches young, urban parents when they need it most. These findings reiterate calls from parents and carers documented in previous work19 and indicate that an effective, sustained way of building knowledge has not yet been found. Gaps in current primary care approaches to ear health and hearing checks are demonstrated. The findings also document the challenge for parents and carers of establishing a diagnosis of persistent ear disease. They shine a light on the impacts on children and families as they wait for care that they perceive effectively addresses their child’s ear, hearing and communication problems. The findings include recommendations contributed by parents and carers on how services can improve their ways of working.

Of note, evidence-based ear health prevention messages, such not smoking around children, were rarely mentioned by parents or carers. There is a need to make an explicit link between these messages and ear health, also noted by Jeffries-Stokes et al.20

There is an evident need to provide young parents with clear information that enables them to look for and respond to the early signs of otitis media and associated hearing loss. Most signs parents and carers currently depend on are unreliable21, nonspecific (e.g., crying) or indicative of later-stage impacts of auditory deprivation, including speech delay and behaviour problems. Frustratingly, the most common form of otitis media experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children frequently occurs without obvious signs.16,18 However, it is a useful learning, unique to our findings, that parents and carers are noticing problems by watching their child’s listening behaviour at home: these behaviours are reliable indicators of hearing status.22 Guiding parents to observe how their child is listening in everyday life and systematically capturing this knowledge using screening tools22 is likely to result in earlier detection of hearing loss before it impacts communication and behaviour significantly.

The relationship between families taking action for ear health concerns, and confidence that they will feel welcome and understood at health services, stood out strongly. This is a fundamental, ongoing and previously documented barrier to care for urban families.9,23 Health services are encouraged to read parents’ and carers’ recommendations for improving cultural safety, health promotion and reach into communities.

The findings highlight the importance of primary health services using effective approaches to checking young children’s ears and hearing. In the documented journey stories, parents and carers were almost always the initiators of the ear health checks that started their child’s journey. Although guidelines16 recommend health practitioners encourage parents and carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children to request ear checks at every visit, this should not be the only thing relied upon. Indeed, without a system that supports this, parents’ and carers’ requests for ear checks may wane. The lack of a proactive approach to ear checks means that children who show no obvious signs, whose parents and carers have not noticed or recognised signs or do not feel confident to request checks, may be rarely checked. Health practitioner responses confirm that checks are not undertaken routinely but on presentation of symptoms or parent or carer concern: problematic for an often-asymptomatic condition. The finding that ear checks are not effectively reaching young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aligns with other research.24 It is encouraging that ear checks are undertaken during child health checks, but uptake of child health checks is not consistently high for children in the critical 0–2-year age range.25 There is a need for a minimum schedule of effective ear health and hearing checks for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in primary care.

The findings indicate that long-term ear health and hearing problems are being managed as a series of discrete episodes. This also appears unique to our findings. If the condition is not being recognised as chronic, this can cause developmental, communication and behavioural impacts on the child and family, and delayed access to specialist care for persistent problems. Diagnosis of most chronic presentations of otitis media is achieved through clinical observation of the condition at two time points, three months apart.16 This approach is reliant on regular monitoring and continuity of care, and on clinical knowledge of when the condition can no longer be regarded as transient. Although not documented in the data, difficulties in establishing a diagnosis of a chronic condition may be amplified for families who do not have continuity of primary health care. In this scenario, obtaining an ear check and providing the right information to establish a chronic diagnosis, triggering appropriate management and referrals, may increasingly become a matter of chance. This is too great a risk, given the prevalence and nature of otitis media in urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and the implications it has for their development and futures. Development of patient databases that capture ear health information in a categorical format that supports diagnosis and management of persistent problems, and that is accessible between health services, would assist primary health practitioners to more easily monitor and manage this condition.

Strengths and limitations

The Urban Hearing Pathways project team was intersectoral. Team members came from community-controlled and mainstream health, and the hearing, science, research, early childhood and not-for-profit community sectors. Six of the 13 key project team members were Aboriginal. The project had a flexible study model, which enabled modifications to accommodate COVID-19 restrictions. Regular project team reviews facilitated action–response refinements to research practice.

Because of COVID-19 social distancing requirements there were significantly reduced opportunities for direct face-to-face or small group discussions with participants, a significant feature of the original research design. Information shared by parents and carers who were able to take part in in-person, small focus-group discussions was richer relative to one-parent interviews, particularly those conducted virtually. Two of the three local health districts from which parent/carer participants were recruited took part in the study. Where they did not participate, the perspectives of staff and clientele of those services, including those identifying as Aboriginal, could not be represented. Because of a range of factors, including varied participation from services and the effects of COVID-19, participant samples varied significantly across the three sites, making geographical comparisons unfeasible.

Recommendations for future research

Research exploring why ear health and hearing checks are, and are not, carried out routinely in primary care is warranted. Research is underway aimed at developing recommendations that define the components of, and a minimum schedule for, effective ear health and hearing checks. A follow-up project aimed at scoping the implementation of these recommendations is recommended. Research that leads to effective ways of building parents’ and carers’ hearing health knowledge at the right points in young children’s lives is much needed.

Conclusion

This study reveals that the onus for identifying ear health and hearing problems often rests with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents and carers, but that they do not feel well equipped to do so. Parents and carers ask that young parents be taught the signs to look for, the actions to take, and how best to support their children’s ear health, hearing and communication development.

Persistent otitis media appears prone to being viewed in primary care through an acute, short-term lens, with respect to both management of, and impacts on, the child. Emerging knowledge about developmental impacts arising from prolonged otitis media–related auditory deprivation in early childhood6,8, and existing knowledge around the exacerbating effects of co-existing factors such as socio-economic disadvantage26, should prompt the establishment of a more systematic approach to identifying and monitoring ear health and hearing problems for this population.

The findings demonstrate the burden carried by families as they wait for effective care. Although stories of family resilience, advocacy and support for children with long-term problems are heartening, these findings highlight the need for a primary health system that is sensitive and responsive to persistent ear health and hearing problems in young, urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners and Custodians of the Awabakal, Worimi, Whadjuk Noongar, Jagera, Yuggera and Ugarapul lands on which our study took place, who have allowed this important research to be undertaken in their communities and welcomed the entire research team willingly. The Urban Hearing Pathways project was funded by the Australian Government Department of Health. It was established by Hearing Australia and the National Acoustic Laboratories, undertaken in partnership with community-based Aboriginal and non-Indigenous project officers and Aboriginal research officers, with guidance from the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation and relevant state affiliates including the Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council. We would like to acknowledge the support of Awabakal Aboriginal Medical Service, Derbarl Yerrigan Health Service, Kambu Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Corporation for Health, the Midvale Hub including the Swan Child and Parent Centre, West Moreton Health and Hunter New England Local Health District. We would also like to express our thanks for the invaluable work of Roderick Wright, Jed Fraser, Ruth McLeod, Amit German and Dr Teresa Ching.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, invited.

Copyright:

© 2021 Harkus et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Gunasekera H. Summary of ear and hearing data from the SEARCH study. Darwin: Otitis Media Australia; 2018. Available from authors.

- 2. Swift VM, Doyle JE, Richmond HJ, Morrison NR, Weeks SA, Richmond PC, et al. Djaalinj Waakinj (listening talking): rationale, cultural governance, methods, population characteristics – an urban Aboriginal birth cohort study of otitis media. Deaf Educ Intl. 2020;22(4):255–74. CrossRef

- 3. Williams CJ, Coates HL, Pascoe EM, Axford Y, Nannup I. Middle ear disease in Aboriginal children in Perth: analysis of hearing screening data, 1998–2004. Med J Aust. 2009;190(10):598–600. CrossRef | PubMed

- 4. Hearing Australia. Demographic details of young Australians aged less than 26 years with a hearing loss, who have been fitted with a hearing aid or cochlear implant. Sydney: Hearing Australia; 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 22]. Available from: www.hearing.com.au/HearingAustralia/media/assets/Documents/2020-Demographics-of-Aided-Young-Australians-at-31-December-2020.pdf

- 5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health performance framework 2020: 1.15 ear health. Canberra: AIHW; 2020 [cited 2021 Sep 22]. Available from: www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/1-15-ear-health

- 6. Bell MF, Bayliss DM, Glauert R, Harrison A, Ohan JL. Chronic illness and developmental vulnerability at school entry. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20152475. CrossRef | PubMed

- 7. Su J-Y, Guthridge S, He VY, Howard D, Leach AJ. Impact of hearing impairment on early childhood development in Australian Aboriginal children: a data linkage study. J Paediatr Child Health. 2020;56:1597–606. CrossRef | PubMed

- 8. Simpson A, Sarkic B, Enticott JC, Richardson Z, Buck K. Developmental vulnerability of Australian school-entry children with hearing loss. Aust J Prim Health. 2020;26:70–5. CrossRef | PubMed

- 9. Scrimgeour M, Scrimgeour D. Health care access for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People living in urban areas, and related research issues a review of the literature. Darwin: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2008 [cited 2021 Sep 22]. Available from: www.lowitja.org.au/content/Document/PDF/DP5_final-pdf.pdf

- 10. Spurling GKP, Askew DA, Schluter PJ, Simpson F, Hayman NE. Household number associated with middle ear disease at an urban Indigenous health service: a cross-sectional study. Aust J Primary Health. 2014;20:285–90. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Herring S, Spangaro J, Lauw M, McNamara L. The intersection of trauma, racism, and cultural competence in effective work with Aboriginal people: waiting for trust. Aust Soc Work. 2013;66(1):104–17. CrossRef

- 12. Gunasekera H, Morris PS, Daniels J, Couzos S, Craig JC. Otitis media in Aboriginal children: the discordance between burden of illness and access to services in rural/remote and urban Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009;45:425–30. CrossRef | PubMed

- 13. Gotis-Graham A, Macniven R, Kong K, Gwynne K. Effectiveness of ear, nose and throat outreach programmes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2020;10:3038273. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. Young C, Gunasekera H, Kong K, Purcell A, Muthayya S, Vincent F, et al. A case study of enhanced clinical care enabled by Aboriginal health research: the Hearing, EAr health and Language Services (HEALS) project. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;40(6):523–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 15. Young C, Tong A, Gunasekera H, Sherriff S, Kalucy D, Fernando P, Craig JC. Health professional and community perspectives on reducing barriers to accessing specialist health care in metropolitan Aboriginal communities: a semi‐structured interview study. J Paediatr Child Health. 2017;53(3):277–82. CrossRef | PubMed

- 16. Menzies School of Health Research. Otitis media guidelines for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research; 2020 [cited 2021 Sep 22]. Available from: www.menzies.edu.au/icms_docs/324012_Otitis_Media_Guidelines_2020.pdf

- 17. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016 Census. Canberra: ABS; 2017 [cited 2021 Sep 22]. Available from: www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/Home/2016%20QuickStats

- 18. Rosenfeld RM, Culpepper L, Yawn B, Mahoney MC, for American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Otitis Media With Effusion. Otitis media with effusion clinical practice guideline. Am Fam Physician. 2004;6(12):2776–9. CrossRef | PubMed

- 19. Australian Government Department of Health. Indigenous ear health research to inform social marketing campaigns: final report. Canberra: Department of Health; 2010 [cited 2021 Oct 19]. Available from: www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/oatish-indigenous-ear-health-toc

- 20. Jeffries-Stokes C, Lehmann D, Johnston J, Mason A, Evans J, Elsbury D, Wood K. Aboriginal perspective on middle ear disease in the arid zone of Western Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2004;40:258–64. CrossRef | PubMed

- 21. Montgomery D. About half of children under age 3 whose parents suspected acute otitis media have the diagnosis; restless sleep, ear rubbing and fever are not predictive. Evid Based Nurs. 2011;14(1). CrossRef | PubMed

- 22. Ching TYC, Hou S, Seeto M, Harkus S, Ward M, Marnane V, Kong K. The Parents’ evaluation of Listening and Understanding Measure (PLUM): development and normative data on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children below 6 years of age. Deaf Educ Int. 2020;22(4):288–304. CrossRef

- 23. Lau P, Pyett P, Burchill M, Furler J, Tynan M, Kelaher M, Liaw ST. Factors influencing access to urban general practices and primary health care by Aboriginal Australians – a qualitative study. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 2012;8(1):66–84. CrossRef

- 24. Western Australian Auditor General. Western Australian Auditor General’s report. Improving Aboriginal children’s ear health. Perth: Office of the Auditor General Western Australia; 2019 [cited 2021 Sep 22]. Available from: audit.wa.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Improving-Aborignal-Childrens-Ear-Health.pdf

- 25. Commissioner for Children and Young People Western Australia. Developmental screening overview and areas of concern. Perth: Commissioner for Children and Young People Western Australia; 2020 [cited 2021 Sep 22]. Available from: www.ccyp.wa.gov.au/our-work/indicators-of-wellbeing/age-group-0-to-5-years/developmental-screening

- 26. Roberts JE, Rosenfeld RM, Zeisel SA. Otitis media and speech and language: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3):e238–48. CrossRef | PubMed