Abstract

The allocation of a significant amount of new funding for health promotion in Australia through the National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health (2009–14) created a unique opportunity to implement a comprehensive approach to the prevention of chronic diseases and demonstrate significant health improvements. Building on existing health promotion infrastructure in Local Health Districts, the NSW Ministry of Health adopted a scaled-up state-wide capacity-building model, designed to alter policies and practices in key children’s settings to increase healthy eating and physical activity among children. NSW also introduced a performance monitoring framework to track implementation and impacts. This paper describes the model that NSW developed for monitoring state-wide programs in the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program and presents the model’s application to early childhood education and care and primary school settings, including current results. This approach to monitoring the scaling up of program implementation at the state-wide level has potential for more widespread application in other policy areas in NSW.

Full text

Introduction

In November 2008, the Council of Australian Governments entered into the National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health (NPAPH), which committed funds to all states and territories to address the increasing prevalence of chronic disease through promoting healthy lifestyle behaviours to children, young people and adults, and investing in the evidence base necessary for effective prevention through national programs in chronic disease risk factor surveillance, translational research and evaluation.1 In NSW, NPAPH funding brought new resources of more than $89 million over four years to deliver settings-based programs to promote healthy eating, physical activity and healthy weight. More than half the allocation was for the Healthy Children Initiative (HCI). This represents the single largest investment in the prevention of chronic disease and health promotion in Australia.2

In this paper, we describe the model developed in NSW to monitor state-wide programs for the central component of the HCI, the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program, and present the model’s application to early childhood education and care services and primary schools, including results to March 2014.

Prevention infrastructure in NSW

Before implementation of the HCI in July 2011, NSW had established infrastructure for the delivery of health promotion programs. NSW health services were delivered across eight Area Health Services (AHSs) until 1 January 2011, when 15 Local Health Districts (LHDs) were formed. Under both structures, designated health promotion teams have been the mainstay of health promotion delivery across NSW, with a senior manager and dedicated staff in each AHS or LHD. Funding arrangements include a budget allocated by the NSW Government, with some teams receiving additional funding from their local services.3 Introduction of Australian Government funds to be used for HCI programs increased financial resources.

State-wide implementation of childhood obesity prevention programs in early childhood education and care services and government primary schools was initiated in mid-2008. Health promotion services were allocated specific funds to deliver centrally coordinated programs that had demonstrated promise in achieving positive changes in key health-related behaviours, including fundamental movement skills, participation in physical activity, increased fruit and vegetable consumption, and reduced consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods.4–8 Furthermore, there was evidence that achievement of broad program reach in a variety of settings and consistent adoption of health promoting practices would reduce the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity. Good for Kids, Good for Life, a five-year demonstration in the Hunter New England region of NSW, showed that a settings-based capacity-building approach yielded a 1% per year decrease in overweight and obesity.9

Through state-wide implementation, program reach was gradually increasing in NSW, but meeting the requirements of the NPAPH required a substantial increase in the scale of delivery across the state, as well as the ability to report on program reach and outcomes. Achieving this increased activity required a model to guide implementation in LHDs, targets for program reach, definition of desired impacts in settings, and a mechanism to monitor program reach and adoption as defined by the specified organisational impacts.

The implementation of the HCI presented an opportunity for a more systematic approach to monitoring program implementation, to ensure accountability for the substantial additional funds the initiative provided.

Implementation of the NSW Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program

Implementation of the HCI began in 2011 based on an agreed NSW HCI implementation plan, including a portfolio of strategies to be delivered in key children’s settings.10 The plan included the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program, representing scaled-up delivery of existing universal primary strategies being delivered in early childhood education and care and government primary school settings since 2008.

The Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program involved cross-sectoral partnerships, and a capacity-building and organisational change approach. This approach is consistent with theoretical and practical approaches to building organisational capacity to support health promotion activities11, and the theoretical approach taken by health promoting schools.12

The program theory assumes that financial, infrastructure and human resource inputs in key children’s settings would facilitate implementation of policies and practices that encourage children to eat healthily and be physically active, and that would, over time, become integrated into the day-to-day organisation and practices of these settings. If achieved, these would result in changes in targeted health behaviours such as increased fruit and vegetable consumption, increased participation in physical activity at recommended levels, and reduced sedentary activity, as well as reduced consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods. In the longer term, these behavioural changes would contribute to reduced prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity.

Monitoring the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program

The performance monitoring framework for the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program sought to facilitate greater consistency of service delivery so that the desired organisational impacts were achieved in all sites participating in the program. The framework was designed to support planning and implementation of local service delivery, as well as state-wide monitoring and reporting against agreed targets. In doing so, it reflected the respective roles of the Ministry of Health as system manager and LHDs in delivering services to meet population health goals.

The Ministry provided funds for LHDs across NSW to deliver the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program and procured providers to deliver training. Targets for reach and adoption were set and monitored. Health promotion teams were responsible for managing service delivery, including determining local implementation strategies and approaches, engaging early childhood education and care services and primary schools, providing ongoing implementation support to facilitate program adoption in participating sites, and reporting progress against achievement of targets to the Ministry.

The performance framework included two levels of indicators: service delivery indicators and indicators of adoption of specific organisational practices. The service delivery indicators were intended to monitor service reach, follow-up and support by LHD staff, and program participation by sites. These indicators supported local health promotion managers and their teams to plan, tailor and monitor service delivery locally. They also allowed the Ministry to monitor program participation across LHDs to support NPAPH reporting obligations to the Australian Government Department of Health.

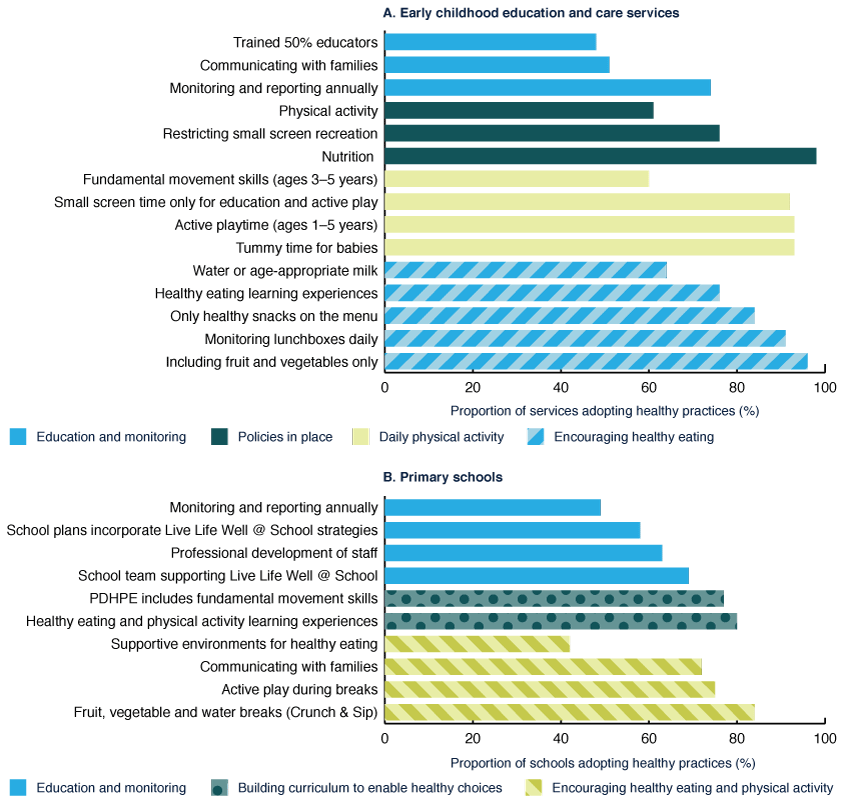

A key aspect of the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program was the development of a set of key practices for early childhood education and care services and primary schools that reflected the policy contexts of each setting. These key practices, represented in Figure 1, describe the organisational (policy, training and information, planning and monitoring), healthy eating and physical activity actions that, when implemented, indicate program adoption, and enhanced capacity for health promotion in these settings. They reflect those actions that, if embedded into the organisation, would result in changes in children’s health behaviours and a subsequent reduction in the population prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity. The key practices apply to all early childhood education and care services and primary schools participating in the program, and guide the nature and focus of implementation support delivered to individual sites by LHD staff.

The adoption indicator assesses the extent to which the agreed key practices have been adopted within individual sites and across settings at the LHD and state levels. The practices relate to both the program (e.g. teaching of fundamental movement skills to students) and the broader organisation (e.g. development of nutrition and physical activity policies). An important aspect of the adoption indicators is that they are linked to key performance indicator (KPI) targets in service level agreements between the Ministry and the LHD. This means that health promotion activity and targets are embedded in local reporting in the same way as clinical activity and targets, raising the profile of population health within the system more broadly.

An overview of the application of the performance monitoring framework and current achievements in the early childhood education and care services and primary schools is described below. Delivery of the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program at scale in these settings reaches very large numbers of children, and achieving a high level of program adoption across both settings will be crucial to influencing children’s health-related behaviours.

The monitoring framework in early childhood and primary school settings

NSW set a delivery target for the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program of at least 80% of early childhood education and care services and primary schools participating by June 2015. Furthermore, significant targets for adoption of key practices were set over a longer time frame, with participating sites adopting up to 80% of key practices in both centre-based early childhood education and care services and primary schools.

By 2010, approximately 50% of preschools and 30% of government primary schools were participating in the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program, and work had begun to extend the reach into long day-care settings and the Catholic and independent education sectors.13 As of March 2014, LHDs across NSW were delivering the program to approximately 80% (2757 of approximately 3400) of early childhood education and care services, and 71% (1859 of approximately 2600) of primary schools.

Across NSW, 55% of early childhood education and care services, and 64% of primary schools had adopted more than 70% of the key program practices. Although there was variability among LHDs, all were considered on track to achieve the June 2014 target of 50% of participating sites adopting 70% of program practices in both settings, and 13 of 15 adoption targets had already been met. Figure 1 shows adoption of each key practice by early childhood education and care services and primary schools participating in the program at March 2014.

Across both settings, practice adoption has been variable. Within individual services and schools, the health promoting practices have been more widely adopted than organisational practices such as training, leadership and monitoring. In the early childhood education and care setting, adoption ranges from 45% for providing information to families to almost 100% for having a written nutrition policy. In the primary school setting, more than 80% of schools report incorporating fruit and vegetable breaks into their daily routine, while less than 50% monitor and report on activity to promote healthy eating and physical activity each year.

Figure 1. Proportion of early childhood education and care services and primary schools adopting healthy eating and physical activity practices, NSW, March 2014

Source: Population Health Intervention Management System Interim Solution

Source: Population Health Intervention Management System Interim Solution

Discussion

Through existing health promotion teams in LHDs, NSW had an infrastructure to deliver state-wide programs and, before the NPAPH, had transitioned to a state-wide approach to program implementation in key settings. However, there were weaknesses, such as lack of clarity around a specific model to guide implementation in LHDs, definition of desired reach and impacts, and mechanisms to monitor reach and impacts over time. The NPAPH provided an opportunity to increase the reach and impact of the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program by developing a more systematic and consistent approach to program implementation and monitoring.

The implementation of a performance monitoring system has given access to specific information about the organisational impacts of the program, and also informs quality improvement at both the state and local level. At the state level, strategies can be put in place to target increased uptake of practices with lower levels of adoption, such as communication to parents, staff training and professional development. Locally, health promotion managers and team members can use the information to better identify the needs of individual sites for support, and to track local trends to enable adjustments to be made to local implementation planning and strategies, as required. Thus, in NSW, performance monitoring becomes a useful feedback process to support improvements in delivery and impact, as well as a mechanism to ensure that targets are met.

Interest in this program across the early childhood education and care sector is so strong that NSW is ahead of its progressive target for organisational reach in this setting, and is on track to achieve the target in the primary school setting. Health promotion staff can now focus more effort and time on providing the type and intensity of support required by sites to enable them to improve the quality of their adoption of the health promotion and organisational practices described above. This augurs well for attaining population-level reductions in childhood overweight and obesity. Between 2004 and 2010, the rate of overweight and obesity in NSW children appeared to have plateaued below 23%10, suggesting that scaled-up implementation of state-wide programs was having a positive impact on rates of childhood overweight and obesity through promoting healthy eating and physical activity. Coupled with the results of the Good for Kids, Good for Life program9, the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program suggests that delivering programs at scale and seeking to influence specific organisational practices is a potentially successful approach to delivering programs in these settings, and may result in future reductions in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among children in NSW.

One advantage of the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program at scale is that the majority of the target population in specific settings was reached by an evidence-based program. Further, the implementation model and approach to monitoring should result in establishment of health promoting practices that are likely to be sustained over time. Of course, further tracking of practices in future years is required to confirm the extent to which adoption of practices is sustained over an extended length of time, and to determine the level of ongoing contact required to ensure that organisational impacts are sustained over time. Understanding the longer-term sustainability of organisational practice changes and the support required to maintain these changes is an area for future investigation.

Negotiating the inclusion of KPIs specific to the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program in service level agreements between the Ministry and LHDs was central to this systematic approach to program implementation and monitoring. It resulted in a high level of senior management interest and engagement in achieving health promotion program outcomes, a much higher level of scrutiny than had been previously applied to health promotion programs, and engendered local health district executive engagement to drive local performance.

Within both the early childhood education and care and primary school settings, national and state policies may have facilitated a high level of uptake of some key organisational practices. For example, to attain national accreditation, early childhood services are required to have a food policy, and, in primary schools, some aspects of the mandated curriculum overlap with the key organisational practices of the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program. Resources from the Healthy Children Initiative provided practical support to help services achieve accreditation. Nonetheless, the early childhood education and care and primary school settings are the two largest target settings for childhood obesity prevention programs in NSW, and each has its own context-specific issues and challenges. The success of a systematic performance monitoring framework in these settings demonstrates the potential usefulness of this approach in other children’s settings, as well as more broadly across the prevention system.

Box 1. Lessons learnt

We were able to develop this framework because:

Tips for successful performance monitoring:

|

There is a risk that a systematic and centrally directed approach to implementation and performance monitoring acts as a barrier to local innovation, and may compromise program fidelity. However, within the context of the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program, whereas the outcomes and targets are centrally directed, LHD implementation to achieve these targets is locally determined. Thus there is a balance between local innovation and central control.

As yet, there is no direct evidence of the population impact of the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program on the health of children. Further work in this area will add to the evidence generated by the Good for Kids, Good for Life program by examining the strength of links between adoption of the Children’s Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Program practices by target organisations, and health behaviours and outcomes in children. This will, in part, be addressed in future population surveys, including the Schools Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey, and the Child Health Survey in NSW.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contributions of Andrew Milat, Liz King and Neil Orr to the development of the Healthy Children Initiative, the Ministry of Health (in particular the Centre for Population Health and the Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence), Population Health Intervention Management System Steering Committee Members, and the Directors and staff of Health Promotion Services across NSW, as well as current members of the Healthy Children Initiative team – Christine Innes-Hughes, Amanda Lockeridge and Kym Buffet.

Copyright:

© 2014 Farell et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms

References

- 1. Council of Australian Governments. National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2008 [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/content/npa/health_preventive/national_partnership.pdf

- 2. National Preventative Health Taskforce. National Preventative Health Strategy – the roadmap for action. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2009.

- 3. NSW Department of Health. Annual Report NSW Health 2008-09. Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 2009 [cited 2014 Jun 21]; Available from: https://www0.health.nsw.gov.au/pubs/2009/pdf/annualreport09.pdf

- 4. Miller M, Newell S, Huddy A, Adams J, Holden L, Dietrich U. Tooty Fruity Vegie Project: process and impact evaluation report. Lismore, NSW: Northern Rivers Area Health Service; 2001

- 5. Hardy LL, King L, Kelly B, Farrell L, Howlett S. Munch and Move: evaluation of a preschool healthy eating and movement skill program. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:80. CrossRef | PubMed

- 6. Wright JE, Konza DM, Hearne D, Okely AD. The Gold Medal Fitness Program: a model of teacher change. Phys Educ Sport Pedag. 2008;13(1):49–64. CrossRef

- 7. Adams J, Pettit J, Newell S. Final report to National Child Nutrition Program on Phase 2 (2002−2003). Lismore, NSW: Community Health Education Groups; 2004 [cited 2014 Jun 21]. Available from: https://epubs.scu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1135&context=educ_pubs

- 8. van Beurden E, Barnett LM, Zask A, Dietrich UC, Brooks LO, Beard J. Can we skill and activate children through primary school physical education lessons? "Move it Groove it"– a collaborative health promotion intervention. Prev Med. 2003;36(4):493−501. CrossRef

- 9. Wiggers J, Wolfenden L, Campbell E, Gillham K, Bell C, Sutherland R, et al. Good for Kids, Good for Life, 2006−2010: evaluation report. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2013.

- 10. Commonwealth of Australia. Implementation plan for the Healthy Children Initiative. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2012 [cited 2014 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/content/npa/health_preventive/healthy_children/NSW_IP_2013.pdf

- 11. Hawe P, Noort M, King L, Jordens C. Multiplying health gains: the critical role of capacity-building within health promotion programs. Health Policy. 1997;39(1):29–42. CrossRef

- 12. World Health Organization. What is a health promoting school? Geneva: World Health Organization [cited 2013 Jun 22]; Available from: https://www.who.int/school_youth_health/gshi/hps/en/

- 13. Hardy LL, Espinel P, King L, Cosgrove C, Bauman A. NSW Schools Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey (SPANS) 2010: full report. Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 2010.