Abstract

Objectives: Medicine reviews are an opportunity to identify and address inappropriate prescribing. The aim of this study was to explore changes in benzodiazepine use among older Australians following a medicine review.

Study type: Retrospective observational cohort study using linked administrative data.

Methods: We used Medicare Benefits Schedule and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme claims from a random 10% sample of Medicare beneficiaries. We identified people aged 65 years or older who received a medicine review in 2013–14 and were using benzodiazepines at the time of review. We identified a propensity score matched comparison cohort of those using benzodiazepines who did not receive a review. Two outcome measures were used: any benzodiazepine use and changes to the quantity of benzodiazepines dispensed (diazepam equivalents) from baseline to 90 and 180 days following a medicine review.

Results: We identified 4002 people using benzodiazepines on the day of their medicine review, of whom approximately one-third discontinued benzodiazepines within 90 days (29.7%) and 180 days (36.4%) after the review. We observed a similar discontinuation rate in the comparison group (32.6%, p = 0.006; and 38.0%, p = 0.12, respectively). In people who were dispensed lower quantities of benzodiazepines (less than 250 mg of diazepam equivalents in the 90 days before the medicine review), we found that 50.3% ceased using benzodiazepines or used lower quantities (measured as diazepam equivalents) following the medicine review (28.7% and 19.7%, respectively). We also observed a reduction in the quantities used in people where initial exposure was high (3.4% ceased; 59.4% decreased). We observed a similar change in volume within the matched comparison group.

Conclusions: Medicine reviews are not associated with any additional reduction in benzodiazepine use among older adults, up to 180 days after review, beyond what was observed in the general population.

Full text

Introduction

Potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIP) to older adults is widespread, with estimates of 11–90% of older adults being exposed to such practices worldwide. The prevalence of PIP tends to be higher in those more susceptible to harm, such as hospitalised older adults, those with dementia or those residing in aged care facilities.1-3

Benzodiazepines are the most commonly reported potentially inappropriate class of medicine used in older adults worldwide4; a recent Australian study found that 15.3% of Australians aged 65 years or older were prescribed at least one benzodiazepine in 2016.5 Although benzodiazepines provide short-term relief from anxiety and insomnia6, they are associated with serious adverse health effects in older adults, such as cognitive impairment, delirium, falls and withdrawal phenomena6, and have a substantial impact on quality of life.7

A variety of initiatives have been investigated to reduce PIP in general, as well as specifically targeting benzodiazepines in older adults. Examples include those focusing on reducing initiation, such as the ‘Choosing Wisely’ campaign8, and those promoting de-prescribing, such as medicine reviews. Although the success of benzodiazepine de-prescribing depends on a number of factors, including dose and chronicity of use9, processes such as medicine reviews are putatively an important initial step in identifying PIP.

In Australia, Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS)–subsidised medicine reviews are performed by pharmacists with the aim of optimising prescribing.10 Despite more than 140 000 MBS-subsidised medicine reviews each year in Australia, there is limited evidence for their effectiveness in remediating PIP. For instance, few studies have investigated the impact of medicine reviews on prescribing, and systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational and experimental studies have failed to identify consistent impacts on outcomes such as mortality and hospitalisation.10,11 The same is true of medicine reviews and benzodiazepine use in older adults. Although uncontrolled observational studies have reported reductions in benzodiazepine prescribing (alone or as a composite measure in the Drug Burden Index) following a medicine review, evidence from randomised controlled trials is inconsistent.1,12,13

We aimed to investigate the real-world impact of medicine reviews on benzodiazepine use in older adults. Specifically, we compared benzodiazepine use following a medicine review with benzodiazepine use among a matched cohort of people who did not receive a review. We also examined the potential for reduction in benzodiazepine dose (tapering) by estimating changes in the volume of benzodiazepines dispensed, measured in diazepam equivalents. We stratified analyses by dose at the time of the review to account for known differences in de-prescribing success relative to starting dose.

Methods

Study design and data sources

We performed a retrospective cohort study using linked administrative data from a random sample of 10% of Australian Medicare beneficiaries. The data included individual-level MBS and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) claims from 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2015. The MBS data include claims for subsidised MBS services; the PBS data include claims for dispensing of PBS-listed medicines, including the date of dispensing, form and strength, and quantity dispensed.

Study population

Our eligible study population included any person aged 65 years or older dispensed at least one benzodiazepine any time between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2014.

Outcome measures

Our outcomes measures were any benzodiazepine use and total quantity of benzodiazepine dispensed (diazepam equivalents) at 90 and 180 days following medicine review. We identified PBS-subsidised benzodiazepines using Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes (N05BA12, N05BA01, N05BA04, N05CD02, N05CD07). As PBS data do not include information of intended dose or duration of treatment, we defined benzodiazepine exposure by calculating an estimated period of exposure (EPE) for each benzodiazepine. We defined the EPE as the number of days by which 75% of people who were dispensed a benzodiazepine received a subsequent dispensing of the same medicine.14 This method has been shown to account for seasonality, adherence and changes in dose.15 We prefer it to other measures, such as defined daily dose, which is not appropriate to assess exposure for medicines with high dosage variability such as benzodiazepines.16

We considered a person exposed to benzodiazepines at 90 and 180 days following the medicine review if the EPE for any new benzodiazepine dispensing following the medicine review overlapped with these dates. We also examined the potential for tapering benzodiazepine use by comparing the quantity of benzodiazepines dispensed (diazepam equivalents)9 in the 90 days before the medicine review (baseline) with the quantity dispensed in days 1–90 and 91–180 after the review. We calculated the quantity of benzodiazepines by summing diazepam equivalents in each dispensing over the relevant period. We calculated diazepam equivalents per dispensing by multiplying pack size by the respective conversion factor.

Medicine reviews

We used MBS claims to identify people who received a medicine review in the community or in residential aged care settings (MBS item codes 900 and 903, respectively). For people with multiple medicine reviews within the study period, we examined only the first medicine review.

Cohort creation

We identified a cohort of people who received a medicine review who were likely to be using benzodiazepines at the time of the review (i.e. if the benzodiazepine EPE overlapped with the date of the medicine review; Supplementary Figure 1, available from: handle.unsw.edu.au/1959.4/resource/collection/resdatac_1102/1).

To assess the extent to which changes in benzodiazepine exposure could be attributed to medicine reviews, we identified a comparison cohort using propensity scores. We chose our propensity score matching variables based on ability to predict the probability of a person receiving a medicine review17, and included variables relating to patient demographics, benzodiazepine exposure, other medicine dispensing, and health service utilisation (Supplementary Table 1, available from: handle.unsw.edu.au/1959.4/resource/collection/resdatac_1102/1). As the comparison population did not have a medicine review date, and there is seasonal variation in the matching variables18, we matched people who received a medicine review to all potential comparison patients by year and month of the medicine review. Our potential comparison population included all people who were using benzodiazepines on the 15th of the month (as a surrogate review date), removing people from the potential pool of comparators once they had been matched. To ensure that we matched people with similar levels of benzodiazepine use before the medicine review, we matched on the quantity of benzodiazepine dispensed (diazepam equivalents). We used the MatchIt Package in R (Stanford, CA: Ho et al., Stanford University; v3.0.2) with one-to-one matching using the nearest-neighbour method.

Statistical analyses

We characterised people by age and sex at the time of the medicine review. As a medicine review may be indicated by the number of medicines being used, we counted the number of unique medicines dispensed in the 90 days before baseline. For each person, we counted the number of benzodiazepine dispensings during this period, as well as ‘baseline use’, measured as diazepam equivalents9 and categorised as low (<250 mg), medium (250–500 mg) or high (>500 mg). We also identified any comorbidities that were pharmacologically treated in the year before the medicine review using the RxRisk algorithm19, as well as the number of unique general practitioner (GP) and specialist providers during this period.

We assessed balance in characteristics of the matched populations using the standard difference – the difference in mean outcome divided by the pooled standard deviation. We considered a standard difference less than 0.2 indicative of balance between medicine review and comparison groups.20

We used chi-square tests to compare differences between medicine review and comparison groups in benzodiazepine exposure at both 90 and 180 days. To measure changes in the quantity of benzodiazepine use, we identified the proportion of people who increased, decreased or had no change in the volume of benzodiazepines dispensed in the two follow-up time periods, compared with the volume dispensed at baseline. We also measured the proportion of people who had no benzodiazepines dispensed in the 1–180 days after the medicine review, to identify those who ceased benzodiazepine use.

As people at different levels of benzodiazepine use will have a different capacity to cease treatment, we stratified all analyses on the volume of benzodiazepine exposure before the medicine review.

All analyses were performed using R (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; v3.6.1) and SAS (Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; v9.4).

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the NSW Population & Health Services Research Ethics Committee (Sub Study Reference Number: 2019UMB0206).

Results

We identified 4002 people aged 65 years or older using benzodiazepines on the day of their first medicine review in 2013–14. The population was predominantly female (68%), with a median age of 82.9 years. The population had high levels of service utilisation (median 19 GP consultations in the previous year) and had been dispensed a median of 10 different medicines (Table 1). The matched comparison group was similar to people who received a medicine review across all measured characteristics (standard difference < 0.2), although the comparison group had a lower proportion who were dispensed antipsychotics and medicines to treat dementia (Table 1; Supplementary Table 2, available from: handle.unsw.edu.au/1959.4/resource/collection/resdatac_1102/1).

Table 1. Characteristics of people who received a medicine review and were exposed to benzodiazepines at the time of review, and a matched comparison group who were exposed to benzodiazepines but did not receive a medicine review

| Characteristic | People who received a medicine review | Comparison group | ||

| n | % of N | n | % of N | |

| Number of people (N) | 4002 | 100 | 4002 | 100 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 2720 | 68.0 | 2661 | 66.5 |

| Male | 1282 | 32.0 | 1341 | 33.5 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 65–75 | 807 | 20.2 | 901 | 22.5 |

| 76–85 | 1603 | 40.0 | 1700 | 42.5 |

| 86–95 | 1427 | 35.7 | 1243 | 31.1 |

| 95+ | 165 | 4.1 | 158 | 3.9 |

| Number of unique medicines dispensed in previous 90 days | ||||

| 0–5 | 422 | 10.5 | 509 | 12.7 |

| 6–10 | 1846 | 46.1 | 1897 | 47.4 |

| 11+ | 1734 | 43.3 | 1596 | 39.9 |

| Number of benzodiazepine dispensings in previous 90 days | ||||

| 1 | 872 | 21.8 | 922 | 23.0 |

| 2–4 | 2299 | 57.4 | 2442 | 61.0 |

| 5+ | 831 | 20.8 | 638 | 15.9 |

| Volume of benzodiazepines (as diazepam equivalents) dispensed in previous 90 days | ||||

| Low (0–250 mg) | 1465 | 36.6 | 1465 | 36.6 |

| Medium (251–500 mg) | 1458 | 36.4 | 1458 | 36.4 |

| High (501+ mg) | 1079 | 27.0 | 1079 | 27.0 |

| Number of GP consultations in previous year | ||||

| 0–9 | 564 | 14.1 | 590 | 14.7 |

| 10–19 | 1476 | 36.9 | 1648 | 41.2 |

| 20–29 | 955 | 23.9 | 955 | 23.9 |

| 30+ | 1007 | 25.2 | 809 | 20.2 |

| Number of specialist consultations in previous year | ||||

| 0 | 2410 | 60.2 | 2139 | 53.5 |

| 1+ | 1592 | 39.8 | 1863 | 46.5 |

| Number of unique GPs and specialists providing consultations in previous year | ||||

| 0–1 | 699 | 17.5 | 586 | 14.6 |

| 2–3 | 1686 | 42.1 | 1629 | 40.7 |

| 4–5 | 954 | 23.8 | 1023 | 25.6 |

| 6+ | 663 | 16.6 | 764 | 19.1 |

Changes in benzodiazepine use at 90 and 180 days

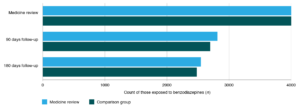

We found that 29.7% of people who received a medicine review discontinued benzodiazepines at 90 days follow-up, and 36.4% discontinued at 180 days (Figure 1). We observed similar reductions in use among the comparison cohort at both 90 and 180 days follow-up (32.6% and 38.0%), but with a slightly higher reduction in use in the comparison cohort (p = 0.006, p = 0.12, respectively).

Figure 1. Number of people exposed to benzodiazepines at the time of medicine review, and 90 days and 180 days follow-up, and a matched comparison group who were exposed to benzodiazepines but did not receive a medicine review (click to enlarge)

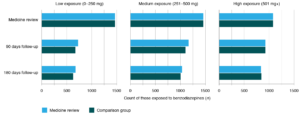

We observed a decrease in the number of people using benzodiazepines at 90 days, with a further modest reduction at 180 days, irrespective of the level of benzodiazepine use before the medicine review (Figure 2; Supplementary Table 3, available from: handle.unsw.edu.au/1959.4/resource/collection/resdatac_1102/1). The decrease was most pronounced among people with the lowest levels of use (50.4% reduction at 90 days and 53.8% at 180 days), followed by people with a medium level of use (20.2% reduction at 90 days and 29.1% at 180 days) and the highest levels of use (14.4% reduction at 90 days and 22.5% at 180 days). In those with low and medium levels of use, a slightly lower proportion of the comparison cohort used benzodiazepines at 90 days follow-up than the medicine review cohort (49.6% and 45.9%, p = 0.04; 79.8% and 75.6% p = 0.007, respectively); otherwise, there was no significant difference in benzodiazepine use between groups.

Figure 2. Number of people exposed to benzodiazepines at the time of medicine review and 90 days and 180 days follow-up, and in a matched comparison group who were exposed to benzodiazepines but did not receive a medicine review, stratified by volume of exposure to benzodiazepines (diazepam equivalents) in the previous 90 days (click to enlarge)

In the 90 days following the medicine review, we found that half (50.3%) of people had a reduction in the quantity of benzodiazepines dispensed, either with no further dispensings (14.5%) or a reduction in quantity (35.9%) (Table 2). A slightly larger proportion of people had a reduction in use in the 91–180 days follow-up period (54.6%). The proportion of people who increased, deceased or had no further dispensings was significantly different between medicine review and comparison populations within both time periods (p < 0.01); more people experienced a decrease in use in the comparison group than in the medicine review group (Table 2).

Table 2. Change in volume of benzodiazepine exposure (diazepam equivalents) from the previous 1–90 days, stratified by baseline exposure to benzodiazepines

| Characteristic | People who received a medicine review | Comparison group | pa | ||

| n | % of N | n | % of N | ||

| Total cohort | |||||

| Number of people (N) | 4002 | 100 | 4002 | 100 | |

| Between medicine reviewb and 1–90 days follow-up | |||||

| No change | 950 | 23.7 | 920 | 23.0 | <0.001 |

| Increase | 1038 | 25.9 | 871 | 21.7 | |

| Decrease | 1435 | 35.9 | 1584 | 39.6 | |

| No subsequent dispensing | 579 | 14.5 | 627 | 15.7 | |

| Between medicine reviewb and 91–180 days follow-up | |||||

| No change | 873 | 21.8 | 899 | 22.5 | 0.009 |

| Increase | 945 | 23.6 | 822 | 20.5 | |

| Decrease | 1605 | 40.1 | 1654 | 41.3 | |

| No subsequent dispensing | 579 | 14.5 | 627 | 15.7 | |

| Low use at baseline (0–250 mg) | |||||

| Number of people (N) | 1465 | 100.0 | 1465 | 100.0 | |

| Between medicine reviewb and 1–90 days follow-up | |||||

| No change | 346 | 23.6 | 337 | 23.0 | 0.02 |

| Increase | 409 | 27.9 | 344 | 23.5 | |

| Decrease | 289 | 19.7 | 338 | 23.1 | |

| No subsequent dispensing | 421 | 28.7 | 446 | 30.4 | |

| Between medicine reviewb and 91–180 days follow-up | |||||

| No change | 324 | 22.1 | 329 | 22.5 | 0.03 |

| Increase | 378 | 25.8 | 312 | 21.3 | |

| Decrease | 342 | 23.3 | 378 | 25.8 | |

| No subsequent dispensing | 421 | 28.7 | 446 | 30.4 | |

| Medium use at baseline (251–500 mg) | |||||

| Number of people (N) | 1458 | 100.0 | 1458 | 100.0 | |

| Between medicine reviewb and 1–90 days follow-up | |||||

| No change | 430 | 29.5 | 394 | 27.0 | <0.001 |

| Increase | 387 | 26.5 | 305 | 20.9 | |

| Decrease | 520 | 35.7 | 629 | 43.1 | |

| No subsequent dispensing | 121 | 8.3 | 130 | 8.9 | |

| Between medicine reviewb and 91–180 days follow-up | |||||

| No change | 388 | 26.6 | 412 | 28.3 | 0.17 |

| Increase | 331 | 22.7 | 283 | 19.4 | |

| Decrease | 618 | 42.4 | 633 | 43.4 | |

| No subsequent dispensing | 121 | 8.3 | 130 | 8.9 | |

| High use at baseline (501+ mg) | |||||

| Number of people (N) | 1079 | 100 | 1079 | 100 | |

| Between medicine reviewb and 1–90 days follow-up | |||||

| No change | 174 | 16.1 | 189 | 17.5 | 0.29 |

| Increase | 242 | 22.4 | 222 | 20.6 | |

| Decrease | 626 | 58.0 | 617 | 57.2 | |

| No subsequent dispensing | 37 | 3.4 | 51 | 4.7 | |

| Between medicine reviewb and 91–180 days follow-up | |||||

| No change | 161 | 14.9 | 158 | 14.6 | 0.49 |

| Increase | 236 | 21.9 | 227 | 21.0 | |

| Decrease | 645 | 59.8 | 643 | 59.7 | |

| No subsequent dispensing | 37 | 3.4 | 51 | 4.7 | |

a Chi-square test for difference in counts between medicine review and comparison group

b For the comparison group, the 15th of the month for which they were matched to a medicine review patient

We found that more than one-quarter of people with low benzodiazepine use at the time of medicine review had no further benzodiazepine dispensings within 90 days follow-up (28.7%), and around one-fifth (19.7%) had a reduction in quantity dispensed (Table 2). In people with higher levels of use, only 3.4% of people had no further benzodiazepine dispensings within 90 days of medicine review, while 58.0% had a reduction in quantity. We observed similar patterns within 91–180 days follow-up. A significantly higher proportion of people in the comparison cohorts for low or medium use either decreased or ceased their benzodiazepine use at 90 days than patients who had a medicine review (p < 0.01); there was no significant difference among people with high use.

Discussion

This population-level observational study indicates that medicine reviews may have a limited effect on reducing benzodiazepine prescribing in older adults. Although half of older adults who were exposed to benzodiazepines at the time of a medicine review either ceased or decreased their exposure in the following 6 months, the same reduction was observed in similar people who did not receive a medicine review. This change was observed irrespective of benzodiazepine dose at the time of the medicine review. Much of the observed reduction in benzodiazepine exposure in both groups could be the result of regression to the mean, whereby cross-sectional measurements of benzodiazepine use are detecting individuals at outlying points in their health trajectories (e.g. intermittent use).21 This observation is supported by greater reductions in use in the low exposure group than in the medium and high exposure groups.

Prior observational studies of benzodiazepine use following medicine reviews were uncontrolled, and so observed reductions may have been a regression to the mean rather than an interventional effect.1,22 Evidence from randomised controlled trials has been mixed. A Dutch randomised controlled trial found that community medicine reviews alone had no effect on benzodiazepine dispensings.13 Conversely, an Australian cluster randomised study across 52 nursing homes found significant reductions in benzodiazepine use following a multifaceted intervention involving development of professional relationships, nurse education and medication reviews.23

There are several possible explanations for the lack of additional reduction associated with the intervention (medicine review) observed in our study. Compared with intermittent or one-off use, it is much harder to cease long-term or high-dose benzodiazepine use, as a result of tolerance and withdrawal phenomena.9 Hence, although medicine reviews may effectively identify individuals prescribed benzodiazepines, the subsequent step of de-prescribing may prove too challenging for the review to lead to any changes in benzodiazepine use. There may also be deficiencies in the medicine review process, such as barriers in communication between the pharmacist and GP as a result of siloing of these professional groups.24 Given that those receiving a medicine review had seen a median of three different doctors in the previous year, communication barriers between prescribers may result in difficulties actioning recommendations arising from medicine reviews and may contribute to PIP.

It may be that medicine reviews are most effective when implemented as part of a multifaceted strategy to promote organisational change. Such comprehensive interventions are challenging and costly to implement and incentivise in real-world clinical practice. Further qualitative research on the human and systemic factors influencing the outcomes of a medicine review are needed to understand the observed changes in medicine use.

The core strength of our study is the use of population-based administrative data, providing real-world evidence on the association of medicine reviews with patient care. However, our study does have several limitations. Approximately 10% of benzodiazepine dispensings in Australia occur through the private market25 and so were not recorded in our data. The propensity score matching was based on Medicare claims data, and, although we matched on a large array of factors, there may be further characteristics of patient care we were unable to account for. For example, the higher prevalence of antipsychotic and dementia medicines in our cohort receiving a medicine review may be due to a larger proportion of patients within residential aged care relative to our comparison cohort. Future linkage with aged care data may enable exploration of whether residential aged care status is an effect modifier in reducing benzodiazepine use in older adults.

Conclusion

Benzodiazepine use in older adults is considered to be inappropriate in most instances, yet remains relatively common. This study suggests that medicine reviews, as an opportunity to identify and address inappropriate prescribing, have little impact. Further investigation of the impact of medicine reviews on the PIP of other medicines, as well as the human and systemic factors that influence the outcomes of a medicine review, are needed to fully understand the real-world impact of medicine reviews in Australia.

Acknowledgements

The work detailed in this manuscript was funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre for Research Excellence in Medicines and Ageing grant (#1060407) and a Cooperative Research Centre Project (CRC-P) grant from the Australian Government Department of Industry, Innovation and Science (ID: CRC-P-439). MF is supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (#1139133). We thank the Australian Government Department of Health for supplying the data.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, not commissioned.

Copyright:

© 2020 Coleman et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Castelino RL, Hilmer SN, Bajorek BV, Nishtala P, Chen TF. Drug Burden Index and potentially inappropriate medications in community-dwelling older people: the impact of home medicines review. Drugs aging. 2010;27(2):135–48. CrossRef | PubMed

- 2. Morin L, Laroche ML, Texier G, Johnell K. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults living in nursing homes: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(9):862.e1–9. CrossRef | PubMed

- 3. Roughead EE, Anderson B, Gilbert AL. Potentially inappropriate prescribing among Australian veterans and war widows/widowers. Intern Med J. 2007;37(6):402–5. CrossRef | PubMed

- 4. Motter FR, Fritzen JS, Hilmer SN, Paniz EV, Paniz VMV. Potentially inappropriate medication in the elderly: a systematic review of validated explicit criteria. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74(6):679–700. CrossRef | PubMed

- 5. Brett J, Zoega H, Buckley NA, Daniels BJ, Elshaug AG, Pearson SA. Choosing wisely? Quantifying the extent of three low value psychotropic prescribing practices in Australia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1009. CrossRef | PubMed

- 6. Glass J, Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, Sproule BA, Busto UE. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ. 2005;331(7526):1169. CrossRef | PubMed

- 7. Harrison SL, Kouladjian O'Donnell L, Bradley CE, Milte R, Dyer SM, Gnanamanickam ES, et al. Associations between the Drug Burden Index, potentially inappropriate medications and quality of life in residential aged care. Drugs aging. 2018;35(1):83–91. CrossRef | PubMed

- 8. Choosing Wisely Australia: an initiative of NPS MedicineWise. Canberra: NPS MedicineWise. Recommendations; 2019 [cited 2020 Dec 8]. Available from: www.choosingwisely.org.au/recommendations

- 9. Brett J, Murnion B. Management of benzodiazepine misuse and dependence. Aust Prescr. 2015;38(5):152–5. CrossRef | PubMed

- 10. Wallerstedt SM, Kindblom JM, Nylen K, Samuelsson O, Strandell A. Medication reviews for nursing home residents to reduce mortality and hospitalization: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(3):488–97. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Hatah E, Braund R, Tordoff J, Duffull SB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of pharmacist-led fee-for-services medication review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(1):102–15. CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. Fog AF, Kvalvaag G, Engedal K, Straand J. Drug-related problems and changes in drug utilization after medication reviews in nursing homes in Oslo, Norway. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2017;35(4):329–35. CrossRef | PubMed

- 13. van der Meer HG, Wouters H, Pont LG, Taxis K. Reducing the anticholinergic and sedative load in older patients on polypharmacy by pharmacist-led medication review: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e019042. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. Pottegard A, Hallas J. Assigning exposure duration to single prescriptions by use of the waiting time distribution. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(8):803–9. CrossRef | PubMed

- 15. Pratt NL, Ramsay EN, Kalisch Ellett LM, Nguyen TA, Barratt JD, Roughead EE. Association between use of multiple psychoactive medicines and hospitalization for falls: retrospective analysis of a large healthcare claim database. Drug Safety. 2014;37(7):529–35. CrossRef | PubMed

- 16. Islam MM, Conigrave KM, Day CA, Nguyen Y, Haber PS. Twenty-year trends in benzodiazepine dispensing in the Australian population. Intern Med J. 2014;44(1):57–64. CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. Du W, Gnjidic D, Pearson SA, Hilmer SN, McLachlan AJ, Blyth F, et al. Patterns of high-risk prescribing and other factors in relation to receipt of a home medicines review: a prospective cohort investigation among adults aged 45 years and over in Australia. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e027305. CrossRef | PubMed

- 18. Mellish L, Karanges EA, Litchfield MJ, Schaffer AL, Blanch B, Daniels BJ, et al. The Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme data collection: a practical guide for researchers. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:634. CrossRef | PubMed

- 19. Sloan KL, Sales AE, Liu CF, Fishman P, Nichol P, Suzuki NT, et al. Construction and characteristics of the RxRisk-V: a VA-adapted pharmacy-based case-mix instrument. Med Care. 2003;41(6):761–74. CrossRef | PubMed

- 20. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424. CrossRef | PubMed

- 21. Morton V, Torgerson DJ. Effect of regression to the mean on decision making in health care. BMJ. 2003;326(7398):1083–4. CrossRef | PubMed

- 22. Lenander C, Bondesson A, Viberg N, Beckman A, Midlov P. Effects of medication reviews on use of potentially inappropriate medications in elderly patients; a cross-sectional study in Swedish primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):616. CrossRef | PubMed

- 23. Roberts MS, Stokes JA, King MA, Lynne TA, Purdie DM, Glasziou PP, et al. Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of a clinical pharmacy intervention in 52 nursing homes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;51(3):257–65. CrossRef | PubMed

- 24. Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF. Shared decision-making and interprofessional collaboration in mental healthcare: a qualitative study exploring perceptions of barriers and facilitators. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(5):373–9. CrossRef | PubMed

- 25. Hollingworth SA, Siskind DJ. Anxiolytic, hypnotic and sedative medication use in Australia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(3):280–8. CrossRef | PubMed