Abstract

Smoking prevalence in Australia has decreased by 75% over the past 40 years. A major reduction in disease burden attributed to smoking has occurred in parallel, adjusted for the time lag between tobacco harms and disease occurrence. Yet, paradoxically, governments have seldom invested in tobacco control measures that require a financial outlay, such as social marketing, at required levels for optimal outcomes. The percentage of disease burden caused by smoking in Australia (9.3%) remains higher than that of any other preventable risk factor and the social costs are estimated at $136.9 billion annually. Tobacco control is rightly seen as an Australian public health success story. However, with up to two in three of Australia’s 2.5 million current smokers at risk of dying prematurely from a smoking-related disease, much more needs to be done. In this paper, we explore a brief history of tobacco control in relation to policy reform and recent evidence, and outline the case for re-energising tobacco control at a time when public health has gained new political and social currency.

Full text

Tobacco control in Australia: an unfinished success story

Published evidence on the harms of smoking, beginning in the early 1950s in the UK1 and the US2, was a trigger for slow, incremental tobacco control policy reforms in developed countries as the evidence of health harms strengthened. Slow, incremental reductions in smoking prevalence have followed3, including in Australia, which has since been considered a global leader in tobacco control.4 Early studies focused on lung cancer and on all-cause mortality. Over time, conclusive evidence emerged showing that smoking causes 16 fatal cancer types5 and about 11.5% of cardiovascular disease deaths in Australia, as well as chronic lung disease, diabetes and many other serious illnesses.6

The impact of smoking on health varies over time and among populations, depending on a range of factors, including long-term patterns of smoking and background death rates in the general population. For example, in the UK in the 1960s, smokers had generally not been smoking for a long time, and overall life expectancy was lower.7 At that time, about one in six smokers could expect to die prematurely from their habit; this increased to one in two in the 1980s. A more recent estimate is that about half of all long-term smokers worldwide – and up to two in three current smokers in Australia8 – are expected to die from their habit.9 No other mass-consumed product, used as directed by the manufacturer, causes so many deaths.3

Over the past half-century, Australia (and other high-income countries) has moved from inaction in tobacco control to tentative steps and then stronger action. This has occurred in parallel with gradual societal changes and public awareness that have made reform more acceptable.10 There has been an incremental approach to most reforms. Tiny text warnings grew to large graphic warnings; removal of broadcast tobacco advertising occurred over a five-year phase-out and eventually led to elimination of glossy packaging as a form of product marketing; tentative non-smoking areas in a few public places (e.g. domestic commercial flights in the late 1980s) were scaled up to larger-scale protection from second-hand smoke; the ongoing increases in tobacco tax; the emergence of low-budget antismoking advertisements led by the not-for-profit sector grew to government-funded mass media campaigns; and multiple other reforms, strengthening, step by step.11

The result? In 1974, when authorities in Australia took their first tentative steps towards tobacco control as public policy with the mandating of text warnings on tobacco products, an estimated 58% of Australian men and 28% of women smoked daily.12 This has dropped to 12.2% (males) and 9.9% (females) in 2019.13 Given the well-established harms of smoking, and data showing reductions in associated disease burden, this reduction in prevalence is surely a success story.

The recognition of the effectiveness of multiple reinforcing elements of tobacco control, delivered within a framework, culminated in the only international health treaty to date: the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, adopted in 2003.14 But the story is far from over. The latest evidence suggests that up to 1.6 million Australians alive today are likely to die prematurely from their smoking8 – unless we step up our efforts in tobacco control.

Why should we re-energise tobacco control in Australia?

Two in three smokers risk premature death

In 2015, a prospective study of all-cause mortality in more than 200 000 individuals in Australia found the relative risks of smoking were substantially greater than had been assumed based on summary evidence from the rest of the world.8 It found that up to two in three long-term smokers in Australia are likely to die prematurely from the direct effects of smoking. The data also showed that quitting at all ages was beneficial, with those quitting by age 45 having long-term death rates comparable to those of people who had never smoked.8 The research was acknowledged by government and was referred to in relation to a series of recurrent 12.5% increases in tobacco excise introduced in 2016. This was a good result, with the subsequent Australian Institute of Health and Welfare data showing product price as the leading motivator of quit attempts.15 But is it enough, in the face of such stark data on smoking-caused mortality?

Increasing economic costs

As well as imposing a major burden in the form of premature death and illness, smoking is an increasing cost burden on society. A new study on the social and economic costs of smoking in Australia published in October 2019 estimated that the overall cost burden to the country was more than $136.9 billion per annum.16 This is four times higher than the previous cost estimate, published in 2004, due to the inclusion of “intangible costs” such as loss of life, as well as increases in tangible costs over time. The single largest increase in a tangible cost item was for healthcare, due to the availability over the past 15 years of new, high-cost pharmaceuticals and an exponential increase in hospital costs to treat smoking-caused disease.16

Smoking-related medical costs, incurred by current and former smokers, are increasing more steeply than smoking prevalence is falling. Based on current trends in cancer expenditure, the cost burden to government, community and individuals will continue to escalate17, noting that tobacco use contributes to 22% of the cancer disease burden.6 The health effects of smoking are costing us more than ever. The estimated $15.6 billion in tobacco excise revenue projected for 2020–2118 is dwarfed by the overall costs of smoking to the nation.

Drop in investment in tobacco control

Among a range of coordinated and individual policy measures, the ongoing increase in the price of tobacco products through taxation measures has been one of Australia’s two most effective national tobacco control policy interventions.19 Price goes up; prevalence goes down. The consistent increases in tobacco excise since 2010 have been paralleled by a consistent increase in quitters reporting price as the key driver of their intention to quit.15

Public education through mass media campaigns and social marketing is the other most effective tobacco control intervention, particularly in tandem with price increases. A comprehensive body of research, including a major time-series analysis of quitting behaviour and interventions published in 2008, shows an inverse relationship between excise levels and smoking prevalence, with a synergistic effect when price increases driven by taxation coincide with mass media antismoking campaigns.19 At a whole-of-population level, evidence shows that hard-hitting antismoking campaigns are a “best buy” as a budget investment in tobacco control in high-income countries like Australia.20

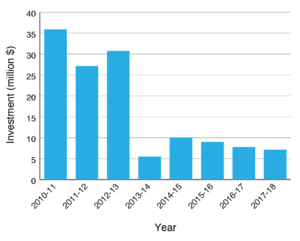

However, over the past decade investment in mass media antismoking campaigns by the Australian, NSW and Victorian governments (the three largest government jurisdictions by constituency and budget) collectively declined from $35 million in 2010–11 to $5.5 million in 2013–14 (Figure 1).21 It then increased to $10 million in 2014–15 before falling away to $7.1 million in 2017–18. Some of the increase was allocated to the antismoking campaign for Indigenous Australians, which should be commended and is achieving strong results.22

Figure 1. Australian, NSW and Victorian Governments’ combined investments in mass media antismoking campaigns, 2010–11 to 2017–1821 (click to enlarge)

Nonetheless, overall investment remains well below international benchmarks.23 This is reflected in reported target audience rating points (TARPs) – the factor used to estimate the effectiveness of advertising on behaviour. Averaged out over the period since 2013, government investment in antismoking campaigns across all national, state and territory jurisdictions has been below the recommended TARP level.23

Although mass media antismoking campaigns are the most expensive population-level tobacco control investment as an outlay, they are also one of the most cost effective.21 A government can make a rhetorical commitment to tobacco control; backing it up with budgeting for antismoking campaigns shows intent.

Opportunities for re-energising tobacco control

Renewed government commitment

There have been encouraging developments in tobacco control in Australia. At the Oceania Tobacco Control Conference in Sydney in October 2019, the Australian Government Minister for Health, Greg Hunt, committed to doubling to $10 million the allocation for a new antismoking campaign in 2020, first announced as $5 million in the May 2019 budget. This came after the Minister’s August 2019 announcement of a goal of reducing Australian smoking prevalence to below 10% by 2025. Tobacco control would also be a pillar of the Minister’s new National Preventive Health Strategy, announced at around the same time.24 Although the campaign strategy may need to be reconsidered in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and response, Minister Hunt’s subsequent public comments remain resolute in support of the strategy and the 2025 prevalence target.25

This renewed commitment ties in with Australia’s fourth intergovernmental National Tobacco Strategy, currently in development. If the next National Tobacco Strategy follows the multifaceted framework of previous strategies, with added emphasis on funding, implementation, reporting and application of the evidence, it should form a blueprint for re-energising tobacco control.26 This framework will also need to follow ‘proportionate universalism’, whereby whole-of-population measures are accompanied by measures tailored to specific groups according to need. The importance of increasing investment in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tobacco control, building on current successes, is a case in point.27

Policy reform and legislation

The Australian Government is also part way through a thematic review of legislation available at the national level, in areas such as product advertising, regulation and Australia’s obligations to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, to further drive down smoking prevalence.28 The point can be made that legislated reforms such as broadcast and print tobacco advertising bans, smoke-free places, graphic warnings and plain packaging can only be introduced once. Such reforms achieve a ‘bounce factor’ – a measurable, immediate response in reduced prevalence – before the decline in smoking prevalence reverts to a steadier downward trend. But they also contribute to the longer-term de-normalisation of smoking. About 60% of the halving of Australian smoking prevalence over the past 25 years is the result of non-smoking young people staying smoke free.

Policy reforms also build a base for stronger, forward incrementalism. Policy frameworks are designed to be reviewed, amended and improved as the evidence changes. Importantly, in the case of antismoking campaigns and price increases, the commitment to strong action can be ongoing. We need more bounces and a stronger long-term de-normalisation effect, which can be achieved by strengthening approaches that have been shown to be effective – cost-neutral policy reforms (such as improved targeting of tax measures, advertising restrictions, retail reform), investment in high-return antismoking campaigns and price control measures that also provide revenue for funded interventions.

There are compelling opportunities for legislation relating to retail supply (licensing, outlet density, tobacco industry kickbacks), advertising (curbing digital tobacco advertising), product regulation (filter capsules, misleading product claims) and smoke-free public places (health facilities, public housing). In the delivery of cessation support, much more can be done to embed quit services into the health system. Improved data collection, using mechanisms such as the Census and the Australian Health Survey, could help make the case for why these reforms are urgently needed. These measures should be underpinned by the most effective form of public education – hard-hitting mass media campaigns that discourage smoking and help pull all the pieces of a comprehensive approach together in a powerful message.

Tobacco control in Australia: a great success story – but far from over

The latest Australian Institute of Health and Welfare data13 shows Australia’s daily smoking rates (for ages older than 14 years) have fallen from 12.2% to 11% in just 3 years (2016–2019), with the proportion of never-smokers (fewer than 100 cigarettes smoked in a lifetime) increasing to an all-time high of 63.1% across all age groups, 76.4% in 18–29 year olds and 96.6% in 14–17 year olds. Bringing our smoke-free younger generations into a lifetime free of tobacco addiction continues to drive the majority of Australia’s achievements in reduced smoking prevalence. However, cessation has also increased. Among smokers, the leading motivation to quit in the latest data was health concerns, despite the under-investment in antismoking campaigns. The positive impact of antismoking campaigns on quit attempts was almost half what it was in 2010 (average of 7.7% in 2019 compared with 13.1% in 2010), reflecting reduced campaign activity. The only specific motivator of quitting that has increased substantially is the impact of price, up from 43% in 2010 to 60% in 2019, paralleling tobacco excise increases over that time.

Australia’s comprehensive, whole-of-government response to COVID-19 shows that our governments and other institutions can come together decisively to deal with a threat to public health. At the time of writing, that response, based primarily on the principle of prevention being better than cure, has kept the COVID-19 death toll in Australia to one of the lowest worldwide. The risk of smoking causing as many as 1.6 million premature, preventable deaths in Australia (up to two-thirds of current smokers) should be enough to galvanise a re-energised, whole-of-government response to tobacco control and overcome any sense of mission accomplished. Tobacco control in Australia is a great success story but it is far from over.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, invited.

Copyright:

© 2020 Grogan & Banks. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Doll R, Hill AB. Smoking and carcinoma of the lung: preliminary report. Br Med J. 1950;2(4682):739–48. CrossRef | PubMed

- 2. Wynder EL, Graham EA. Tobacco smoking as a possible etiologic factor in bronchiogenic carcinoma; a study of 684 proved cases. J Am Med Assoc. 1950;143(4):329–36. CrossRef | PubMed

- 3. World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2020. Tobacco Free Initiative: WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic – previous reports; 2008–2015 [cited 2020 Aug 24]. Available from: www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/previous/en/

- 4. World Health Organisation. Tobacco control country profiles, second edition. Geneva: WHO; 2003 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: www.who.int/tobacco/global_data/country_profiles/en/

- 5. International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, Volume 100 E. A review of human carcinogens: personal habits and indoor combustions. Lyon, France: IARC; 2012. PubMed

- 6. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2019. Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2015. Canberra: AIHW; 2019 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/c076f42f-61ea-4348-9c0a-d996353e838f/aihw-bod-22.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- 7. Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observation on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519. CrossRef | PubMed

- 8. Banks E, Joshy G, Weber MF, Liu B, Grenfell R, Egger S, et al. Tobacco smoking and all-cause mortality in a large Australian cohort study: findings from a mature epidemic with current low smoking prevalence. BMC Med. 2015;13:38. CrossRef | PubMed

- 9. Jha P. Avoidable global cancer deaths and total deaths from smoking. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(9):655–64. CrossRef | PubMed

- 10. Australian Government Department of Health. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Tobacco control timeline; 2018 May 10 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/tobacco-control-toc~timeline

- 11. Greenhalgh EM, Scollo MM, Winstanley MH. Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2012 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: tobacco.cleartheair.org.hk/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Ch11_Advertising.pdf

- 12. Gray N and Hill D. Patterns of tobacco smoking in Australia. Med J Aust. 1975;2(22):819–22. CrossRef | PubMed

- 13. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019. Canberra: AIHW; 2020 [cited 2020 Aug 24]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/3564474e-f7ad-461c-b918-7f8de03d1294/aihw-phe-270-NDSHS-2019.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- 14. World Health Organization. The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: an overview. Geneva: WHO; 2018 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: www.who.int/fctc/WHO_FCTC_summary.pdf?ua=1

- 15. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2016: detailed findings. Canberra: AIWH; 2017 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/15db8c15-7062-4cde-bfa4-3c2079f30af3/aihw-phe-214.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- 16. Whetton S, Tait RJ, Scollo M, Banks E, Chapman J, Dey T, et al. Identifying the social costs of tobacco use to Australia in 2015/16. Sydney: National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University; 2019 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: ndri.curtin.edu.au/NDRI/media/documents/publications/T273.pdf

- 17. Goldsbury DE, Yap S, Weber MF, Veerman L, Rankin N, Banks E, et al. Health services costs for cancer care in Australia: estimates from the 45 and Up Study. PloS One. 2018;13(7):e0201552. CrossRef | PubMed

- 18. Australian Government, The Treasury. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2020. Portfolio budget statements, 2019–20; 2019 April 2 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: treasury.gov.au/publication/portfolio-budget-statements-201920

- 19. Wakefield MA, Durkin S, Spittal MJ, Siahpush M, Scollo M, Simpson JA, et al. Impact of tobacco control policies and mass media campaigns on monthly adult smoking prevalence. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1443–50. CrossRef | PubMed

- 20. World Health Organisation. ‘Best buys’ and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: WHO; 2017 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: www.who.int/ncds/management/WHO_Appendix_BestBuys.pdf?ua=1

- 21. Carroll T, Cotter T, Purcell K, Bayly M. Public education campaigns to discourage: the Australian experience. In: Scollo MM and Winstanley MH, editors. Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2019 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-14-social-marketing/14-3-public-education-campaigns-to-discourage-smoking

- 22. ORC International. Don’t make smokes your story 2018 evaluation. Sydney: ORC International [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/don-t-make-smokes-your-story-campaign-2018-evaluation-report.pdf

- 23. Bayly M, Cotter T, Carroll T. Examining the effectiveness of public education campaigns. In: Scollo MM and Winstanley MH, editors. Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2019 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-14-social-marketing/14-4-examining-effectiveness-of-public-education-c

- 24. Australian Government Department of Health. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. National Preventive Health Strategy; 2020 Jul 28 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/national-preventive-health-strategy

- 25. Ministers: Department of Health. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Minister Hunt’s media: four times as many people trying to quit smoking during COVID-19; 2020 May 31 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-greg-hunt-mp/media/four-times-as-many-people-trying-to-quit-smoking-during-covid-19

- 26. Intergovernmental Committee on Drugs. National Tobacco Strategy 2012–2018. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2012 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/national-tobacco-strategy-2012-2018_1.pdf

- 27. Lovett R, Thurber KA, Wright A, Maddox R, Banks E. Deadly progress: changes in Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adult daily smoking, 2004–2015. Public Health Res Pract. 2017;27(5):2751742. CrossRef | PubMed

- 28. Australian Government Department of Health. Review of tobacco control legislation – update. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2020 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: consultations.health.gov.au/population-health-and-sport-division/review-of-tobacco-control-legislation/