Abstract

Aim: One definition of research co-production is a collaboration between researchers and healthcare professionals throughout a research process to facilitate knowledge translation and improve the clinical impact of research findings. In this paper, we present a case study of clinical research co-production and reflect on how the process was facilitated between researchers and healthcare professionals.

Type of program or service: Development of a novel transdisciplinary assessment for implementation in an acute stroke unit (ASU).

Methods: Researchers and healthcare professionals integrated perspectives and co-produced a novel transdisciplinary assessment. Team-based activities were guided by a logic model, including task analysis and simulation testing. A logframe matrix was used to plan implementation strategies to mitigate potential risks.

Results: Research co-production was fundamental to integrating multiple perspectives to develop an effective, novel transdisciplinary assessment for patients with stroke. Preliminary data demonstrated that the transdisciplinary approach could save up to 103 minutes per patient in assessment time.

Lessons Learnt: As the project evolved, the three most important factors for research co-production were 1) the right people to integrate critical disciplinary and pragmatic perspectives; 2) a project leader who was inclusive of perspectives held by researchers and healthcare professionals, and 3) structured and non-biased team discussions using a theoretical tool. We recommend these three factors be considered in future research co-production in healthcare settings.

Full text

Background

In Australia, there were 27 428 new stroke cases in 2020 and this number is expected to exceed 50 000 by 2050.1 Given the increasing incidence of stroke, it is essential to consider how national stroke guidelines will be met in the future. For example, Australian guidelines state that patients should receive a physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech pathology assessment within 48 hours of admission.2 To meet the guidelines, the allied health workforce is challenged to increase productivity.3 Transdisciplinary care could be a solution.

Transdisciplinary care blurs discipline boundaries and leverages existing disciplinary skills and training to enable health professionals to work beyond their usual scope of practice safely.4–6 Transdisciplinary care limits the repetition of questions and tasks through several professions sharing assessment, intervention, and/or discharge planning elements to enable a single professional to complete the tasks.4–6 We are only aware of two projects that have evaluated the impact of allied health transdisciplinary teams in acute stroke units (ASUs).7,8 While both projects were described in grey literature and neither reported statistically significant results, Reinbott and Murtagh reported a trend towards decreased allied health time providing inpatient care (mean 36.5 minutes) and reduced length of hospital stay (mean 33.9 hours) when a transdisciplinary assessment was implemented.8 Delaney and colleagues did not identify any difference between usual and transdisciplinary care.7 Further research is required in this field.

Co-production is a novel approach to research in transdisciplinary care. While there are many perspectives on what co-production entails, one definition describes research co-production as a mutually beneficial collaboration between researchers and healthcare professionals to identify service needs and priorities, develop research questions and methodology, design tools or interventions, plan and complete data collection, interpret findings, and disseminate research results.9,10 Collaborating throughout the research process can improve the sense of ownership, knowledge translation and uptake of the intervention, dissemination and the impact of clinical studies.11,12 However, there is ambiguity regarding how co-production should be defined, when and how to engage in research co-production, and the interchangeable use of alternate terms.11 This paper aims to reflect on the methods used to develop a transdisciplinary assessment for implementation in an ASU and to provide insights on co-production between healthcare professionals and researchers.

Methods

Clinical Setting

The project was carried out at the ASU at the Mater Hospital Brisbane, in Queensland, Australia.

Project Development

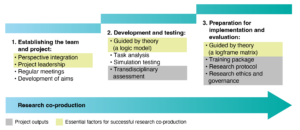

Developing a novel transdisciplinary assessment involved research co-production between healthcare professionals and researchers. As the project evolved, we focused on three important factors, summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of research co-production stages during the development of a transdisciplinary assessment for patients with stroke (click figure to enlarge)

1. Establishing the team and project

The catalyst for the project was feedback from consumers (in this case ASU staff and patients) identifying that allied health assessments were repetitive. ASU staff agreed to respond to the feedback, and the occupational therapist proposed a project to implement a transdisciplinary assessment. At least one member from every discipline in the ASU was invited to join the project. Healthcare professionals (occupational therapists, physiotherapists, speech pathologists, social workers, stroke clinical nurse consultants, nurse educators) and a clinical researcher committed to the project as core group members (see Figure 2). The objective of the core group members was to co-produce a novel transdisciplinary assessment for implementation in the ASU, to reduce allied health assessment duplication and improve time efficiency. The occupational therapist was confirmed as the project leader, a role that involved facilitating fortnightly meetings and learning about research by enrolling in a higher degree by research. Peripheral stakeholders (educators and simulated patients) were involved to contribute their unique perspectives (see Figure 2). Patients will be co-production partners (see Figure 2) in the implementation and evaluation stages of the project (not reported in this case study).

Figure 2. Research co-production team (click figure to enlarge)

2. Development and testing

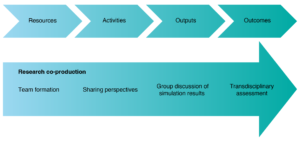

Development of the transdisciplinary assessment was supported by a logic model (Figure 3). Logic models allow visualisation of the project process and identification of areas where further planning or evaluation is required.13 The intuitive structure of the logic model guided the project team to identify available resources, activities to complete, and outputs to generate to achieve the desired outcomes. Research co-production supported each stage of the logic model (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Stages of research co-production mapped to a logic model (click figure to enlarge)

The primary resources identified were various stakeholder perspectives. Co-production commenced alongside team formation, where members discussed project roles and objectives. Next, the core group members undertook a series of co-production activities where expert perspectives were shared and discussed. First, existing allied health assessments were critically appraised, where duplicated questions/tasks were identified (e.g. upper limb assessment was identified on occupational therapy and physiotherapy assessments), and questions/tasks that were safe and appropriate for skill-sharing were identified (e.g. a standardised communication screen usually performed by speech pathologists). All identified tasks/questions were collated to create the first draft of the novel transdisciplinary assessment. Second, the core group members collaborated with experienced educators (peripheral stakeholders) to process-test the new tool using two clinical simulations. The simulations involved a physiotherapy and occupational therapy administrator, two actors simulating patient cases (peripheral stakeholders), and education and clinical staff who observed the simulation testing. Simulations were completed as a quality assurance method (before implementation), where assessment content and flow, standardised and safe administration, and assessment length were evaluated.

Simulation results represented the co-productive output, including data on time taken to complete the transdisciplinary assessment and formal recommendations. The educators facilitated group discussions and provided formal recommendations that encapsulated all perspectives (e.g. one recommendation was to develop competency training to standardise assessment delivery between clinicians). The core group members then discussed recommendations to finalise the outcome for this phase of work, the co-produced transdisciplinary assessment.

3. Preparing for implementation and evaluation

During the development process, it was important to identify and address barriers and facilitators that could influence implementation (not reported in this case study). A logframe matrix was chosen as a planning and monitoring tool. A logframe matrix is designed to be a participatory process that uses ‘if–then’ logic, for example, ‘if implemented, then the outcomes will be achieved’.14

Co-production was supported by using a logframe matrix as a team-based activity to structure discussions and obtain the full range of staff perspectives regarding contextual factors, assumptions, and strategies that could influence the implementation of the transdisciplinary assessment. For example, the core group members assumed that staff from different professional backgrounds could safely administer the transdisciplinary assessment in a standardised manner to obtain reliable and repeatable results. To mitigate the risk of unreliable assessment results, the core group members agreed to develop competency training with guidance from education staff (peripheral stakeholders).

A logframe matrix was also used to guide discussions and perspective sharing around the potential benefits of the transdisciplinary assessment. For each potential benefit identified (e.g. time efficiency), an outcome measure was co-produced to include in the research protocol (e.g. record time taken to complete usual assessments compared to the time taken to complete the transdisciplinary assessment). Collaboration between healthcare professionals and researchers (core group members) was necessary to select outcome measures that were clinically relevant, feasible to collect, and suitable for statistical analysis. The implementation strategies and outcome measures were collated into a research protocol and submitted to the Mater Misericordiae Ltd Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/MML/66933) and the Research Governance Office (MSSA/MRGO/66933).

Results

The objective of the core group members was achieved. Simulation results showed an improvement in allied health time efficiency of 103 minutes per case, as the median total time to administer the transdisciplinary assessment was 42 minutes, compared with a median total time of 145 minutes for the former model of single-discipline assessments. The novel transdisciplinary assessment was considered appropriate for further testing, and we will progress to assessing implementation in the next phase of the research.

Insights and lessons learnt

As the project evolved, we identified three factors most important for co-production.

1. Perspective integration

It was critical to ensure the right people from a breadth of professional backgrounds were involved. Without their necessary perspectives, gaps in thinking and research planning could have hindered the development of the transdisciplinary assessment. We acknowledge that the patient perspective was not represented in the development phase. While this could be viewed as a limitation of the project, patient perspectives will be captured in the next phase of work (implementation and evaluation).

Researchers and healthcare professionals need to find ways to collaborate and co-produce effectively to facilitate perspective integration. We suggest that strategies might be found in the interprofessional collaboration literature for healthcare settings. Interprofessional collaboration is the partnership of healthcare professionals from different disciplines to deliver coordinated healthcare15,16, which resembles our definition of research co-production. We suggest that co-production can be facilitated by member commitment, open communication, interpersonal relationships, trust, respect and understanding of others’ roles and expertise, sharing knowledge, and shared workspaces.4,15,17 Barriers to co-production can include professional culture disparities, role conflicts, power hierarchies, and a sense of competition.4,15,17

2. Project leadership

From our experience, a project leader with a dual perspective was an effective strategy to facilitate co-production, by actively integrating clinical and research perspectives. In this example, the project leader held a clinical perspective and was willing to learn about the research perspective. To reach mutual decisions in project meetings, the project leader encouraged core team members to share their perspectives and used prompts or paraphrasing to integrate missing perspectives. We also suggest that logical alternatives to a project leader with a dual perspective (such as shared leadership between clinicians and researchers) could be trialled in different settings.

3. Planning guided by theory

Theoretical tools were useful to support research co-production by structuring discussions and planning activities. For example, a logic model and logframe matrix were useful for identifying planning activities and guiding group discussions without favouring a healthcare or research perspective. As a result, discussions were structured, less biased, and encouraged contribution from all perspectives. We propose that future research co-production be guided by theory instead of stakeholder agendas or experience, which may be biased towards one perspective.

Conclusion

In this case study, the three most important factors for research co-production included: integration of the right perspectives, inclusive project leadership, and planning guided by neutral theoretical tools. From our experience, we suggest these three elements are essential in future applications of research co-production in healthcare settings.

Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken as part of AM’s Doctor of Philosophy enrolment at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland. AM received financial support from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Mater Misericordiae Ltd, Queensland Health, and the University of Queensland. The authors would like to acknowledge the core group memebrs who collaborated to co-produce this work: Simon Freestone, Caitlin Humphries, Karl Harm, Julia Matthews, Lucy Lyons, Jody Ebenezer, Beth Houghton, Marie McCaig, Ashley McGuire, Brendon Glenn, Ash Gibson, and Felicity Prebble. Thank you to Raymond Kopeshke for reviewing the manuscript concepts and clarity from a health service and management perspective.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, invited.

Copyright:

© 2022 Martin et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Deloitte Access Economics. The economic impact of stroke in Australia, 2020 [Internet]. Sydney (AU): Deloitte Access Economics; 2020 [cited 2021 Aug 3]. Available from: www2.deloitte.com/au/en/pages/economics/articles/economic-impact-stroke-australia.html

- 2. Stroke Foundation. Clinical guidelines for stroke management Melbourne [Internet]. Melbourne (AU): Stroke Foundation; 2021 [cited 2021 Aug 3]. Available from: informme.org.au/Guidelines/Clinical-Guidelines-for-Stroke-Management

- 3. Productivity Commission. Efficiency in health. Canberra: Australian Government; 2015 [cited 2021 Aug 4]. Available from: www.pc.gov.au/research/completed/efficiency-health/efficiency-health.pdf

- 4. Gordon RM, Corcoran JR, Bartley-Daniele P, Sklenar D, Sutton PR, Cartwright F. A transdisciplinary team approach to pain management in inpatient health care settings. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15(1):426–35. CrossRef | PubMed

- 5. Singh R, Küçükdeveci AA, Grabljevec K, Gray A. The role of interdisciplinary teams in physical and rehabilitation medicine. J Rehabil Med. 2018;50(8):673–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 6. Van Bewer V. Transdisciplinarity in health care: a concept analysis. Nurse Forum. 2017;52(4):339–47. CrossRef | PubMed

- 7. Delany K, Pitt R, Perkins K, Phillips R. Transdisciplinary stroke care: perceptions of healthcare teams. Presented at: 13th National Allied Health Conference; 2019 Aug 5–8; Brisbane, Australia [cited 2022 May 10]. Available from: nahc.com.au/2804

- 8. Reinbott J, Murtagh D. Implementation of a transdisciplinary model of care for mild deficit acute stroke patients. Presented at: 13th National Allied Health Conference; 2019 Aug 5–8; Brisbane, Australia [cited 2022 May 18]. Available from: nahc.com.au/2695

- 9. Graham ID, Tetroe JM. Getting evidence into policy and practice: perspective of a health research funder. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18(1):46–50. PubMed

- 10. Kothari A, Wathen CN. A critical second look at integrated knowledge translation. Health Policy. 2013;109(2):187–91. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Oliver K, Kothari A, Mays N. The dark side of coproduction: do the costs outweigh the benefits for health research? Health Res Policy Sys. 2019;17(33). CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. Astell AJ, Fels DI. Co-production methods in health research. In: Knowledge, innovation, and impact: a guide for the engaged health researcher. Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2021 p. 175–82. CrossRef

- 13. Melle EV. Using a logic model to assist in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of educational programs. Acad Med. 2016;91(10):1464. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. Ringhofer L, Kohlweg K. Has the theory of change established itself as the better alternative to the logical framework approach in development cooperation programmes? Prog Dev Stud. 2019;19(2):112–22. CrossRef

- 15. Eaton B, Regan S. Perspectives of speech-language pathologists and audiologists on interprofessional collaboration. Can J Speech-Lang Pathol Audiol. 2015;39(1):6–18. Article

- 16. Flores-Sandoval C, Sibbald S, Ryan BL, Orange JB. Healthcare teams and patient-related terminology: a review of concepts and uses. Scand J Caring Sci. 2021;35(1):55–66. CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. Fink-Samnick E. Leveraging interprofessional team-based care toward case management excellence. Professional Case Manag. 2019;24(3):130–41. CrossRef | PubMed