Abstract

Collaboration between community members, researchers, and policy makers drives efforts to solve complex health problems such as obesity, alcohol misuse, and type 2 diabetes. Community participation is essential to ensure the optimal design, implementation and evaluation of resulting initiatives. The terms ‘co-creation’, ‘co-design’ and ‘co-production’ have been used interchangeably to describe the development of initiatives involving multiple stakeholders. While commonalities exist across these concepts, they have essential distinctions for public health, particularly related to the role of stakeholders and the extent and timing of their engagement. We summarise these similarities and differences drawing from the cross-disciplinary literature, including public administration and governance, service management, design, marketing and public health. Co-creation is an overarching guiding principle encompassing co-design and co-production. A clear definition of these terms clarifies aspects of participatory action research for community-based public health initiatives.

Full text

Background

Increasing the participation and involvement of key stakeholders (e.g. employers, partners, customers, citizens, policy makers, end-users) can strengthen innovation, implementation and overall success of population health initiatives.1,2 Engaging, respecting and applying these multiple perspectives provides context-specific, practical and relevant knowledge with flow-on impacts on health equity, citizenship and social justice.1,3 The engagement of stakeholders in the development and implementation of initiatives is captured under the broader term ‘Participatory Action Research’ (PAR).3 More recently, co-creation, co-design and co-production have been used to describe specific PAR-type methods.

Each of these terms has emerged from different fields and holds nuance in meaning and application depending on the area in which the concept is applied.4 Apart from the differences, the commonality in emphasis is on the input from consumers or citizens in the design and/or delivery of a product, service, initiative or innovation.5 Limited attempts have been made to establish clear differences and applications between these three terms6, although comparisons have been explored between co-creation and co-design7,8 and between co-creation and co-production.9,10 This paper presents distinguishing characteristics between co-creation, co-design and co-production, and provides a perspective to integrate co-production and co-design into an overarching approach for designing, implementing, and evaluating effective public health initiatives. To our knowledge, this is the first time that co-creation has been presented as an overarching construct that includes co-design and co-production for guiding public health initiatives.

Terminology uses and distinctions

Different aspects help to differentiate co-creation, co-design and co-production. Table 1 summarises key factors that separate these three terms, with distinctions made to highlight the specific attributes observed in the literature when referring to each term.

.

Table 1. Distinctions between the terms co-creation, co-design and co-production

| Factors | Co-creation | Co-design | Co-production |

| Focus | Consumer and experience centric Engaging stakeholders High level of information processing |

Centred on consumers’ insights to establish new priorities, plans and strategies for improvement | Production- and company-centric |

| Key stakeholders | All relevant stakeholders involved in the process (e.g., consumers, managers, employees, community) | Service users, implementers, and procurers | Managers and employees |

| Stakeholder role | Very active: provide continuous input to service provider throughout the process Information provider Value creatora |

Active: equal and reciprocal relationship between all stakeholders in the improvement process Useful tool in product and service design |

Passive: rely on the influence of the physical environment provided Perceived as a resource Describe acceptability and feasibility of pre-determined strategy |

| Stakeholders’ participation | Repeated interactions and transactions across multiple channels Help to produce knowledge and skills Collaborative cooperation in all steps of the process from problem definition, design of solutions, and implementation and evaluation of changes. |

Consumers co‐lead the development, design, implementation and evaluation of activities, products and services | Mainly at the end of the value chain |

| Communication | Ongoing dialogue with diverse stakeholders Bidirectional and transparent communication |

Trusting and open communication | Listening to consumers Less transparent |

| Value creation (e.g. psychological, economic value or a social good) | Creation of unique personalised experiences – ownership and engagement in subsequent action | Intrinsic values of the process. Lived experiences of all parties involved add value to the final product or service |

Extraction of economic value Quality products and services |

| Resultant initiative | Is created with consumer engagement at all stages of problem definition, boundary-setting etc | Designed with a clear outcome in mind but consumer engagement to firm boundaries and approaches | Designed prior to engagement with consumer |

| Possible outcomes | Creates value of a good or service using the views of diverse stakeholders | Improved design outcomes and enhanced social inclusion | Enhances the value of a good or a service |

Sources: Chathoth et al.11, Ansell and Torfing12, Patient experience and consumer engagement13, Sánchez de la Guía et al.7, Trischler et al.14, Ramaswamy and Ozcan15, von Heimburg and Cluley4.

a A value creator is a stakeholder that is involved in the development and integration of ideas, expectations and roles that add meaning to the outcomes.

Co-creation promotes the creation of value by engaging diverse stakeholders in the process of understanding complex problems, and designing and evaluating contextually relevant solutions (Table 1).15 This value can take multiple forms: for the individual it can be psychological (e.g. feelings of appreciation) or economic (e.g. greater earnings). For organisations, value is most often economic (e.g. lower costs, improved productivity) or a social good.1 Value co-creation can be achieved through the constant feedback from multiple interactions between stakeholders, thereby benefitting the stakeholders involved.

Co-creation refers to the collaborative approach of creative problem solving between diverse stakeholders at all project stages. It emphasises diverse stakeholders at all parts of an initiative process, beginning with determining and defining the problem through to the final stages of a project.12,16 The plan of collaboration is jointly set by co-initiating stakeholders who call for collective action.12,14-16 In public health, these co-initiators could be public agencies (e.g. health departments, community health), stakeholder groups (e.g. patient representatives, maternal and child health nurses) or citizens’ representatives (e.g. breast feeding mothers’ group, active transport lobby) concerned by specific issues such as neighbourhood crime, equal access to healthcare or environmental concerns.14 For example Brimblecombe et al.17 engaged community members, retailers and academics to create a transformative problem-solving solution in remote community stores in Australia. The co-creation process involved identifying the need for a healthier food retail environment, the co-design of a feasible strategy to achieve identified solutions (i.e. restricting merchandising of discretionary foods), and the optimisation of resources to sustain the implementation. The results reported an overall reduction in sales of targeted confectionery and sugary drinks as a result of a co-created initiative that benefited both retailers and public health.

Co-design describes active collaboration between stakeholders in designing solutions to a prespecified problem. It promotes citizen participation to formulate or improve specific concerns (i.e. service or product improvement, better prevention activities, more resources, better trained health promotion staff and, evidence informed initiatives).7 Co-design is not always formally documented and can take the form of group problem solving, critically after the problem has been determined.18 Bogomolova et al.19 describe co-design as a seven-step systematic method that was used to develop a program that promoted health and wellbeing in a supermarket in collaboration with consumers, supermarket staff and academics. The process involved a series of co-design workshops to generate creative solutions for a storewide implementation program. Due to the high volume of ideas and strategies, these were reviewed by retailers and academics in collaboration, to prioritise and implement the most attainable strategies and create a route for next iterations of the program. Results showed that the chosen strategies helped to increase consumers’ knowledge about healthier food choices. This study shows the importance of collaborating with stakeholders from the early stages of the co-creation process through co-design, which can enable successful implementation and positive results.

Co-production engages stakeholders in the implementation of a previously agreed solution (strategy) to a previously agreed problem and focuses on how to allocate resources and assets within these constraints, to achieve better outcomes.7,12,20 Etgar20 suggests that co-production occurs after the initiative was designed and takes place at the point of implementing the initiative. Sharpe et at.6, describes the development of services for children and young people living with diabetes in East London through a process of co-production. The process involved consulting young people to better understand barriers and options they encountered after receiving a diabetes diagnosis and in using National Health Service services and the type of changes they would like to see. Their input led to a series of planning sessions between health practitioners to transform the local health diabetes services. Through this co-production process, young people were identified as essential agents for the delivery of these improved services. This example differs from co-design, as the goal was to improve an already available service that could be optimised. In this sense, the delivery of the health service could not be successfully co-produced without the input of the consumers.

Co-creation engages stakeholders before the problem is defined and considers that stakeholders (e.g. suppliers and consumers or citizens) are not necessarily on opposite sides but can collaborate to find new shared values and opportunities for mutual benefit in defining the problem and subsequent solutions.21 The extent and timing of stakeholder engagement are critical distinctions between co-creation, co-design and co-production (Table 1). Since co-design serves as a tool for co-creation, and co-creation involves different stakeholders in the co-production of a service, co-design and co-production can be positioned under the umbrella of co-creation. The principles of open innovation and participatory design have helped to integrate and disseminate co-creation as a reference to participation in complex problems.18

Co-creation approaches are difficult to compare due to the variety of context where they are applied.18 Yet the principles of participation, involvement, and engagement from participatory action research can serve as a guide to frame and contextualise interactions of co-creation in practice1,22, as these conditions are essential for co-creation.15 Greenhalgh, et al.1 identified four significantly diverse health initiatives that – at a co-creation level – have a common emphasis on power-sharing, reciprocity and mutual learning between stakeholders.

Co-creation as an overarching approach for practice

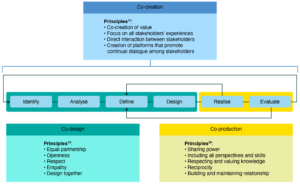

Co-creation aligns with participatory research23, engaging stakeholders in co-design or co-production approaches15 and enables those stakeholders to construct a shared agenda that facilitates a collective action, creating useful solutions.18,24 de Koning et al.25, analysed and clustered12 models of co-creation into a six-step continual research cycle. We used this framework to prototype the use of co-creation as an overarching concept that involves co-design and co-production (Figure 1). Figure 1 represents co-creation as a linear process, yet it entails continual improvement of outputs or outcomes as an incremental change and transformative innovation.12

Figure 1. Model for co-creation of public health initiatives (click on figure to enlarge)

Adapted from: de Koning et al.25

The six steps shown in Figure 1 are described below:

- Identify: identification of the structures and stakeholders relevant to the issue of interest. The focus of this step is on the identification of opportunities for value creation and solutions for problems.26 It is important to recognise all the stakeholders that should be included in the process.24

- Analyse: analysis of the stakeholder network and identification of shared and conflicting values to systematically clarify the processes and options for decision making, nature of relationships and relevant obligations among these relationships.26 Part of this process involves understanding how stakeholders interact together and understanding relevant experiences and ideas for possible solutions.24

- Define: built on the rights, obligations, and ideas identified in previous steps, participants prioritise problems, next steps and actions.26

- Design: design of initiatives by setting goals, actions to achieve those goals, evaluation processes and allocation of resources and assets. To get the right initiative, stakeholders need to collaborate and adapt their positions of value from learnings gained through interactions.26

- Realise: during the implementation, stakeholders test the designed strategies and gather information. This realisation stage can remain continuous or occur in stages where testing ideas are reevaluated.26 It is essential to build structures that enable continual dialogue between stakeholders to implement ideas and generate further ideas for improvement and future implementation.24

- Evaluate: during the evaluation step, the proposed outcomes are assessed, as well as the way previous steps were taken, the learnings from the diverse stakeholders, the changes in the environment and ways for sustainability (e.g., resources, new partnerships, capacity building).24

Co-design prioritises the expertise and knowledge as essential resources in the design process7 and emphasises equal and reciprocal relationships among all stakeholders (Figure 1).13 We consider that the nature and methods of co-design can ensure the meaningful involvement of stakeholders during the first four steps (identify, analyse, define and design).27 Stakeholder involvement that goes beyond occasional participation or consultation is essential for the relevant design of solutions that suit the context of the involved parties.4,12,14,15 Active involvement requires power-sharing between stakeholders and a joint action that recognises trust and mutual dependence.12,13,28 Following the design stage, co-production will aid an effective realisation of the project. The perspectives and skills of stakeholders are central for the co-production of knowledge in the evaluation stage, which will inform the identification stage and relationship continuation, thereby promoting a continual cycle.16,29 Research co-design and co-production have established a set of principles that help create an environment that promotes equal partnership and values the knowledge and expertise of those involved in the process.13,28 The key principles for research co-production28 and co-design13 can guide the co-creation process so that the design, realisation and evaluation of an initiative ensure equity, citizenship and social justice.

Conclusion

Our understanding of co-creation is framed and contextualised within PAR. It provides basic steps and considerations to identify the specific issues to be addressed to inform the design of an initiative. The key principles suggested by co-design of strategies and co-production literature are required for enhanced social inclusion and empowerment. Co-creation is considered an overarching construct which is defined as the active involvement of stakeholders, from the exploration and articulation of problems or needs to the creation, implementation and evaluation of solutions or initiatives.15,16 In this vision, co-design relates to the design of an initiative that positions participants’ needs, expertise and knowledge at its centre. Co-production assists in the collaborative delivery and production of knowledge.

Acknowledgements

CV and JW are supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) funded Centre of Research Excellence in Food Retail Environments for Health (RE-FRESH) (APP1152968). The opinions, analysis, and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the NHMRC.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, invited.

Copyright:

© 2022 Vargas et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Greenhalgh T, Jackson C, Shaw S, Janamian T. Achieving research impact through co-creation in community-based health services: literature review and case study. Milbank Q. 2016;94(2):392–429. CrossRef | PubMed

- 2. Verloigne M, Altenburg TM, Chinapaw MJM, Chastin S, Cardon G, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Using a co-creational approach to develop, implement and evaluate an intervention to promote physical activity in adolescent girls from vocational and technical schools: a case control study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(8):862. CrossRef | PubMed

- 3. Schneider B. Participatory action research, mental health service user research, and the hearing (our) voices projects. Int J Qual Methods. 2012;11(2):152–65. CrossRef

- 4. von Heimburg D, Cluley V. Advancing complexity-informed health promotion: a scoping review to link health promotion and co-creation. Health Promot Int. 2021;36(2):581–600. CrossRef | PubMed

- 5. Alford J. The multiple facets of co-production: building on the work of Elinor Ostrom. Public Manag Rev. 2014;16(3):299–316. CrossRef

- 6. Sharpe D, Green E, Harden A, Freer R, Moodambail A, Towndrow S. 'It's my diabetes': co-production in practice with young people in delivering a 'perfect' care pathway for diabetes. Research for All. 2018;2(2):289–303. CrossRef

- 7. Sánchez de la Guía L, Puyuelo Cazorla M, de-Miguel-Molina B. Terms and meanings of "participation" in product design: From "user involvement" to "co-design". Des J. 2017;20(Sup 1):S4539–51. CrossRef

- 8. Sanders EB, Stappers PJ. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign. 2008;4(1):5–18. CrossRef

- 9. Terblanche NS. Some theoretical perspectives of co-creation and co-production of value by customers. Acta Commercii. 2014;14(2):a237. CrossRef

- 10. Brandsen T, Steen T, Verschuere B. Co-creation and co-production in public services: Urgent issues in practice and research. In: Brandsen T, Steen T, Verschuere B, editors. Co-production and co-creation: engaging citizens in public services. New York and London: Taylor & Francis Group; 2018. p. 3–8. CrossRef

- 11. Chathoth P, Altinay L, Harrington RJ, Okumus F, Chan ES. Co-production versus co-creation: a process based continuum in the hotel service context. Int J Hosp Manag. 2013;32(1):11–20. CrossRef

- 12. Ansell C, Torfing J. Public governance as co-creation : A strategy for revitalizing the public sector and rejuvenating democracy. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 2021. CrossRef

- 13. NSW Government Agency for Clinical Innovation. Patient experience and consumer engagement. a guide to build co-design capability. NSW, Australia: ACI; 2019 [cited 2021 Sep 1]. Available from: aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/502240/Guide-Build-Codesign-Capability.pdf

- 14. Trischler J, Dietrich T, Rundle-Thiele S. Co-design: from expert- to user-driven ideas in public service design. Public Manag Rev. 2019;21(11):1595–619. CrossRef

- 15. Ramaswamy V, Ozcan K. The co-creation paradigm. Stanford, (CA): Stanford University Press; 2014. CrossRef

- 16. Voorberg WH, Bekkers VJ, Tummers LG. A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag Rev. 2015;17(9):1333–57. CrossRef

- 17. Brimblecombe J, McMahon E, Ferguson M, De Silva K, Peeters A, Miles E, et al. Effect of restricted retail merchandising of discretionary food and beverages on population diet: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4(10):e463–73. CrossRef | PubMed

- 18. Jones P. Contexts of co-creation: Designing with system stakeholders: Theory, methods, and practice. In: Jones P, Kijima K, editors. Systemic design translational systems sciences. Tokyo: Sptinger; 2018. p. 3–52. CrossRef

- 19. Bogomolova S, Carins J, Dietrich T, Bogomolov T, Dollman J. Encouraging healthier choices in supermarkets: a co-design approach. Eur J Mark. 2021; 55(9):2439–63 CrossRef

- 20. Etgar M. A descriptive model of the consumer co-production process. J Acad Mark Sci. 2008;36(1):97–108. CrossRef

- 21. Galvagno M, Dalli D. Theory of value co-creation: a systematic literature review. Manag Serv Qual. 2014;24(6):643–83. CrossRef

- 22. McIntyre A. Participatory action research. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE Publications Inc.; 2008. CrossRef

- 23. Leask CF, Sandlund M, Skelton DA, Altenburg TM, Cardon G, Chinapaw MJ, et al. Framework, principles and recommendations for utilising participatory methodologies in the co-creation and evaluation of public health interventions. Res Involv Engagem. 2019;5:2. CrossRef | PubMed

- 24. Ramaswamy V, Gouillart F. Building the co-creative enterprise: give all your stakeholders a bigger say, and they'll lead you to better insights, revenues, and profits. Harv Bus Rev. 2010;88(10):100–9. Article

- 25. de Koning JI, Crul MR, Wever R. Models or co-creation. In: Service Design Geographies, editor. Proceedings of the serv des. Conference: Linköping University Electronic Press; 2016. p. 266–78 [cited 2022 May 10]. Available from: www.researchgate.net/publication/303541138_Models_of_Co-creation

- 26. Castro-Martinez MP, Jackson PR. Collaborative value co-creation in community sports trusts at football clubs. Corp Gov. 2015;15(2):229–42. CrossRef

- 27. Slattery P, Saeri AK, Bragge P. Research co-design in health: A rapid overview of reviews. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(1):17. CrossRef | PubMed

- 28. Hickey G, Brearley S, Coldham T, Denegri S, Green G, Staniszewska S, et al. Guidance on co-producing a research project. Southampton; NIHR Involve; 2018 [cited 2021 Sep 1]. Available from: www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Copro_Guidance_Feb19.pdf

- 29. Vargo SL, Lusch RF. A service logic for service science. In: Hefley B, Murphy W, editors. Service science, management and engineering education for the 21st century. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2008. p.83–8. CrossRef