Abstract

Background: Co-design is the latest buzzword in healthcare services and research and is ubiquitous in Australian funding grants and policy documents. There are no standards for what constitutes co-design and it is often confused with less collaborative processes such as consultation. Collective impact is a co-design tool used for complex and entrenched problems. It uses a systematic approach and requires power and resource sharing. We applied collective impact to three research projects with Aboriginal communities. This paper explores how collective impact can enhance participation and outcomes in healthcare services and research.

Methods: We evaluated the collective impact process and outcomes in three translational health research projects with Aboriginal people and communities using a case study approach. We adapted the model using an iterative co-design approach.

Results: We adapted the collective impact model in three ways: 1) replaced the precondition of ‘problems that are urgent’ with ‘problems that are complex and entrenched’; 2) added to the ‘common agenda’ the requirement to establish a planned exit and long-term sustainability strategy from the outset; and 3) added the delivery of a public policy outcome as a result of the collective impact process.

Conclusions: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health is an important public policy priority that requires new and different approaches to service delivery and research. This study adapted the collective impact approach and developed the Rambaldini model through three translational health research case studies and found that a modified collective impact approach is an effective tool for engagement and outcomes.

Full text

Introduction

Co-design is the latest buzzword in healthcare services and research and is ubiquitous in Australian funding grants and policy documents.1 While the intent to engage participants and communities is much needed, the practice is often poor or tokenistic. There are no standards for what constitutes co-design and it is often confused with less collaborative processes such as consultation.1 Collective impact is a co-design tool. Developed by Kania and Kramer, collective impact facilitates the engagement of multiple parties with a stake in highly complex problems to collectively define (and prioritise) problems and develop, implement and evaluate solutions.2,3 Collective impact requires parties to pool and share resources, and no party can act without the authority of the whole. This creates complexity, but it also means that each stage is agreed and the measures of success are defined and measured by the collective impact group or groups.2,3 Collective impact has proven effective at facilitating solutions for highly complex problems across a wide range of social issues and has some emerging evidence internationally showing that it can measurably improve outcomes in areas such as teen pregnancy, youth outcomes and climate change literacy.4-9 More recently, in Australia, it has been effective in improving oral health and building the Aboriginal health workforce through vocational education.10,11 This paper uses a case study approach to demonstrate how collective impact can enhance participation and outcomes in healthcare services and research.

Collective impact, an approach to co-design

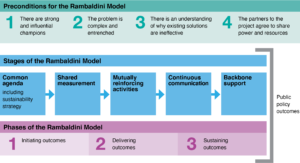

Collective impact includes five stages, shown in Figure 1, and three phases of implementation: planning, delivering and sustaining.12 The five stages of collective impact cycle through each of the three phases as projects mature and develop. Its emphasis on the collective, rather than individuals or hierarchies, aligns well with respectful engagement and decision making with Aboriginal Elders and communities and has enabled significant and measurable improvement to seemingly intractable problems. Prior to initiating collective impact, three preconditions must be met: 1) there are influential champions, 2) an urgent problem, and 3) an understanding of why the existing solutions are not working.12

Figure 1. Collective Impact stages (click figure to enlarge)

Our research team

Our team includes Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal researchers and community leaders. Bundjalung Elder and Associate Professor Boe Rambaldini provides cultural leadership and advocacy of all research. His trusted relationships and respect within communities have enabled research relationships to be made and maintained between community members, clinicians, and health researchers. The Aboriginal Health and Medical Council (AHMRC) Ethics Committee reviewed and authorised all our research. Our research always has Aboriginal researchers and Aboriginal community team members whose expertise is privileged throughout the research process and who are properly recognised as investigators, supervisors and authors. We also seek to recognise community contributions in ways that communities experience as meaningful and significant.

Terminology

Our research team has ongoing discussions about appropriate terminology. We recognise that language use and meaning are constantly changing and, as such, our position on terminology is also dynamic. Our current practice is to use the term Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander when we refer to Indigenous Australian people or communities. We use the term Aboriginal when referring to people in Australian states and territories, except Queensland, where we use Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. We use the specific clan group on advice from local Elders. We use the term Indigenous when referring to First Nations peoples globally except where a more specific term is appropriate.

Methods

Why collective impact?

Despite the limited Australian empirical evidence about collective impact, our team selected it as our research method because of the measurable and structured engagement process, power-sharing, and the consensus-building approach. These features align with Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing2,3,10,12,13 and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines for conducting ethically sound research with Aboriginal communities.14 We also selected this method as it has been championed by a non-Aboriginal researcher (KG) seeking a method that complemented Indigenous research methodologies and could be ethically implemented by non-Aboriginal people. We respect the debates about Aboriginal researchers leading Aboriginal research and believe that co-design and collective impact facilitates Aboriginal ownership, leadership and control. In the three cases presented here, Aboriginal leaders and communities actively influenced the design, implementation and evaluation of services and research through the collective impact process. All three have moved through all phases and stages of collective impact and are in the final stages of research translation.

Results

Applying collective impact to improve oral health in rural and remote NSW

In late 2013 we were invited by Aboriginal communities in the central north of New South Wales (NSW) to initiate a co-design process to help resolve what they described as a 30-year problem.15 The community sought a culturally safe, accessible and sustainable oral health service. We adopted a collective impact approach and worked with these communities to develop a common agenda. We agreed on the initial shared measures of success and explicitly agreed on how the data would be collected, stored and accessed.10,15 Most of the data was collected by community-based clinicians using existing dental practice software and stored and managed by the Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service (ACCHS). Access was governed by the AHMRC Ethics Committee approval and was restricted to staff of the ACCHS who released tranches of de-identified data to the research team for analysis. Clinical and research staff collected additional data, including surveys, interviews, and focus groups. Storage and access were governed through the AHMRC ethics approval and the data management policies of the University of Sydney.

A primary priority for the communities was local skills development and employment. This became a key mutually reinforcing activity because it enabled local employment while people completed nationally recognised qualifications. It also built cultural safety within oral health service delivery and health literacy about oral health promotion and dental treatment within families and communities. Community meetings were initially very frequent (at least weekly) and always scheduled well in advance so people could plan their participation. Continuous communication also included more informal catch-ups, telephone calls, SMS, and email to identify and address issues and opportunities early. The backbone role was shared between the research team which led the ethics, data collection, coordination and reporting aspects, and the ACCHS which led the data management and employment. Funding was jointly managed by the research team and the ACCHS, and the roles and responsibilities were documented in a Memorandum of Understanding.

The outcomes of this work were the co-design and delivery of a highly efficient oral health service16, that was valued by staff and the participating communities.17,18 The service has continued to provide employment opportunities to local community members and supported the attainment of qualifications. There was a reduction in tooth decay and gum disease and increased water consumption and daily tooth brushing for children.11 A sustainable model of routine application of topical fluoride in schools was developed and scaled19,20 and national work was undertaken to enable a public health approach to topical fluoride.21 This process provided the basis for the amended approach to collective impact which has been named the Rambaldini Model of collective impact (see Figure 2), and which is explored in two further case studies.

Figure 2. Rambaldini Model of collective impact (click figure to enlarge)

Applying collective impact to co-design vocational education and workforce development

The correlation between work and health, income and health, culturally safe services, and the likelihood that people will access them are all well established in the literature.22 As such, when Aboriginal people are leading Aboriginal healthcare research and services, the gap in health outcomes is more likely to close. Building on the work of West et al., we used collective impact to co-design a vocational education program to build the Aboriginal health workforce.23,24 Developing a skilled and credentialled Aboriginal healthcare workforce is a mutually reinforcing activity. West et al. found five factors that impacted the completion rate of Aboriginal pre-registration nursing students.23 We adapted this model using collective impact for vocational education and found two extra factors that positively influenced completion. The delivery of vocational courses was then co-designed around the seven factors: cultural, administrative, financial, curriculum, logistical, employment, and personal components.24 The average completion rate for Aboriginal students in vocational education qualifications through TAFE NSW was 29% in 2013.25 Through collective impact, a completion rate of more than 90% was established and maintained over 5 years, with more than 500 qualifications awarded to Aboriginal scholars (Table 1).26 The significance of this work is that, with relatively easy to implement co-designed changes, the completion rate for vocational education by Aboriginal students tripled.

Table 1. Completion rates for co-designed vocational education program among participating Aboriginal students in NSW

| Year | Number of qualifications completed | Completion rate (%) |

| 2015 | 72 | 97 |

| 2016 | 121 | 91 |

| 2017 | 110 | 93 |

| 2018 | 66 | 92 |

| 2019 | 136 | 97 |

| Total | 505 | 93 |

Source: Poche Centre for Indigenous Health, University of Sydney. Available from authors.

Supporting Aboriginal people to complete qualifications equips them to work in local healthcare services and delivers compounding outcomes. These include skills, pride and income for individuals and their families, as well as increasing the likelihood of community members’ culturally safe services.27 The benefit for research practice is the culturally safe participation of Aboriginal people in research that matters to them and the development of high impact translational research methods and reliable results.

Applying collective impact to research about screening for atrial fibrillation

This third case study demonstrates how collective impact enabled culturally safe development of a scientific research protocol to screen for atrial fibrillation (AF). AF is the most common heart arrhythmia and a precursor to stroke. Prior to this work, little was known about the experience of Aboriginal people with AF in a community setting.28

The protocol was developed initially by establishing a common agenda to reduce cardiovascular disease in Aboriginal people. This included developing a process to screen for AF within communities in culturally safe ways, creating access to treatment pathways, and increasing the health literacy of Aboriginal health workers and community members about cardiovascular disease and stroke. As part of this process, measures were agreed upon that would enable prevalence estimates to be established, ensure acceptability of the AF screening process and pathway for each community, and identify a recommended screening age.

Ethical approval for the co-designed protocol was obtained through the AHMRC (1135/15), the Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (CA-17-2755), and the Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC706).

The protocol involved workshopping with Aboriginal health workers regarding using a device and smartphone application (app) to record a 30-second single lead ECG and detect likely AF. This was a mutually reinforcing activity as local community specific procedures were consolidated during workshop activities. A local referral pathway was established for all 16 sites, including ACCHs and other healthcare services across New South Wales (NSW), Northern Territory and Western Australia, so that the study could reliably track the outcomes for each participant. This was the largest trial of screening for AF with Australian Aboriginal people in any setting and the first to be community based (n = 619).29 The key findings were that AF screening with a smartphone device and app was feasible and culturally acceptable.30 It also found that screening for AF must begin at least 10 years earlier for Aboriginal people than recommended in international guidelines.31 The process of translating these findings into policy is currently underway. Key informant consultations have occurred32, and a realist review of studies of AF in Indigenous peoples in high income countries has identified culturally safe strategies to translate the research findings into policy, standards and practice. 33

This study was only possible with respectful relationships, trust and continuous communication between ACCHSs and the research team. The co-design process allowed for local cultural adaptation of the protocol at each site. A simple example of this was at one site; the Aboriginal health worker explained AF to participants as “what this means is that your heart is dancing to a different tune, and we have to help it dance to a healthy tune”. A more complex example of local adaptation was the bespoke referral and management pathways at each site, which included multiple service providers, cultural support and consideration of transport, other logistics, care coordination and communication of results.

Discussion

These three case studies indicate that engaging with Aboriginal people and communities through collective impact to design, implement and evaluate healthcare services and research improves the effectiveness, efficiency and outcomes. Collective impact is a tool that enables effective engagement of researchers with communities such that power and resources are shared, and decision making is genuinely collaborative. These findings tell us that collective impact takes time but can ultimately deliver more efficient solutions. The problems are appropriately understood through community and cultural lenses, and solutions are developed, implemented, and evaluated together. The quality of engagement matters. It is not enough to simply consult. Aboriginal communities understand their problems best, and these three case studies inform us that collaborative problem solving, planning and evaluation are necessary, effective and efficient.

Refining the collective impact approach

Despite the positive findings in our research regarding the use of collective impact, some limitations have been identified. Firstly, collective impact as conceptualised by Kania and Kramer has no end point or explicit exit strategy.2,3 In theory, collective impact projects could remain in phase three indefinitely. However, suppose collective impact is successful and entrenched problems are addressed. In that case, there needs to be explicit and planned ways of shifting resources and power over time and ultimately implementing programs within usual levels of resourcing and management. A planned exit and long-term sustainability strategy was built into the three case studies described in this paper from the conception stage. For example: embedding local workforce development as a mutually reinforcing activity into the oral health project so that the program could eventually be staffed locally; agreeing on the exit/sustainability strategy at the same time as the development of the common agenda, and having a planned handover date from the backbone organisation to local control were implemented to embed our exit from the outset.

Secondly, a precondition of collective impact is urgency. Our research showed that highly complex problems are not always urgent. They require action, but the issue is less about urgency and more about the complexity and entrenched nature of the problem. The Rambaldini model amended the precondition to complexity and entrenchment for collective impact in Aboriginal health research. Thirdly, collective impact explicitly requires power sharing. In the Rambaldini Model, collective impact consists of an additional precondition of partners clear commitment to power and resource sharing. Unless partners in a collective impact project explicitly understand this and agree to act in this way, considerable resources could be expended trying to negotiate the five stages of collective impact when a fundamental aspect of the tool is not agreed upon upfront.

Finally, collective impact projects should have a public policy outcome. It is not enough to resolve a complex or entrenched problem in one place or at one time. Collective impact projects should use their approaches and findings to shape public policy. The three case studies we describe here have sought to influence public policy with respect to Aboriginal health, for example by influencing the funding and design of rural dental services, publishing in the peer-reviewed literature and by co-presenting (with community researchers) the findings of our research to governments, communities and at conferences. Again, this outcome has been added to the Rambaldini Model.

Conclusions

Australian Aboriginal people, along with Indigenous peoples globally, face significant health disadvantage. Cabaj and Weaver argue that despite some problems with the collective impact approach, it is “roughly right” and provides effective mechanisms to bring a range of people and organisations together to make a change.34 Our experience applying collective impact with Aboriginal communities to address complex healthcare services and research problems is that it is a useful tool when applied to the right kind of problems with the right partners. Addressing problems in Aboriginal health is an important public policy priority that requires new and different approaches. The Rambaldini Model is one such tool that has proven effective in engagement and outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Our team are grateful for the contributions and assistance of Aboriginal Elders and community members, clinicians and collaborating ACCHs who have enabled the development of the Rambaldini Model through this work.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, invited.

Copyright:

© 2022 Gwynne et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Blomkamp E. The promise of co-design for public policy. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 2018;77:729–43. CrossRef

- 2. Kania J, Hanleybrown F, Splansky Juster J. Essential mindset shifts for collective impact. Collective Insights on Collective Impact Supplement in the Stanford Social Innovation Review; 2014. [cited May 18] Available from: www.ssir.org/articles/entry/essential_mindset_shifts_for_collective_impact

- 3. Kania J, Kramer M. Collective Impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review; 2011. [cited May 18] Available from: ssir.org/articles/entry/collective_impact

- 4. Banyai C, Fleming D. Collective impact capacity building: finding gold in Southwest Florida. Community Development. 2016;47(2):259–73. CrossRef

- 5. Thomas WK, Saunders E. Using collective impact in support of community-wide teen pregnancy prevention initiatives. Community Development. 2016;47(2): 241–58. CrossRef

- 6. Boyce B. Collective impact: aligning organizational efforts for broader social change. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(4):495–97. CrossRef | PubMed

- 7. Flood J, Minkler M, Hennessey Lavery S, Estrada J, Falbe J. The collective impact model and its potential for health promotion: overview and case study of a healthy retail initiative in San Francisco. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42(5):654–68. CrossRef | PubMed

- 8. Price H, Cohen J. Driving youth outcomes through collective impact. Kennedy School Review. 2015;15:28–33. Article

- 9. Rider S, Winters K, Dean J, Seymour J. The fostering hope initiative. Zero to Three. 2014;35(1):37–42. Article

- 10. Gwynne K, Cairnduff A. Applying collective impact to wicked problems in Aboriginal health. Metropolitan Universities Journal. 2017;28(4):115–30. CrossRef

- 11. Dimitropoulos Y, Holden A, Gwynne K, Do L, Byun R, Sohn W. Outcomes of a co-designed, community-led oral health promotion program for Aboriginal children in rural and remote communities in New South Wales, Australia. Community Dent Health. 2020;37(2):132–37. CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. Hanleybrown F, Kania J, Kramer M. Channeling change: making collective impact work. Stanford Social Innovation Review. 2012. [cited 2022 May 18] Available from: ssir.org/articles/entry/channeling_change_making_collective_impact_work

- 13. Martin KL, Mirraboopa B. Ways of knowing, being and doing: a theoretical framework and methods for indigenous and indigenist re‐search. Journal of Australian Studies. 2003;27(76):203–14. CrossRef

- 14. National Health and Medical Research Council, Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities: guidelines for researchers and stakeholders. Canberra: NHMRC; 2018. [cited 2022 May 18] Available from: nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/resources/ethical-conduct-research-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples-and-communities

- 15. Gwynne K, Irving M, McCowen D, Rambaldini B, Skinner J, Naoum S, Blinkhorn A. Developing a sustainable model of oral health care for disadvantaged Aboriginal people living in rural and remote communities in NSW, using collective impact methodology. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(1):46–53. CrossRef | PubMed

- 16. Gwynne K, McCowen D, Cripps S, Lincoln M, Irving M, Blinkhorn A. A comparison of two models of dental care for rural Aboriginal communities in New South Wales. Aust Dent J. 2017;62(2):208–14. CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. Irving M, Short S, Gwynne K, Tennant M, Blinkhorn A. ‘I miss my family, it's been a while…' a qualitative study of clinicians who live and work in rural/remote Australian Aboriginal communities. Aust J Rural Health. 2017;25:260–7. CrossRef | PubMed

- 18. Irving M, Gwynne K, Angell B, Tennant M, Blinkhorn A. Client perspectives on an Aboriginal community led oral health service in rural Australia. Aust J Rural Health, 2017;25:163–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 19. Dimitropoulos Y, Blinkhorn A, Irving M, Skinner J, Naoum S, Holden A, et al. Enabling Aboriginal dental assistants to apply fluoride varnish for school children in communities with a high Aboriginal population in New South Wales, Australia: A study protocol for a feasibility study. Pilot and Feasibility Stud. 2019;5(1):1–6 CrossRef | PubMed

- 20. Skinner J, Dimitropoulos Y, Masoe A, Yaacoub A, Byun R, Rambaldini B, et al. Aboriginal dental assistants can safely apply fluoride varnish in regional, rural and remote primary schools in New South Wales, Australia. Aust J Rural Health. 2020;28(5):500–5. CrossRef | PubMed

- 21. Skinner J, Dimitropoulos Y, Rambaldini B, Calma T, Raymond K, Ummer-Christian R, et al. Costing the scale-up of a national primary school-based fluoride varnish program for Aboriginal children using dental assistants in Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):8774. CrossRef | PubMed

- 22. Gwynne K, Jeffries T, Lincoln M. Improving the efficacy of healthcare services for Aboriginal Australians. Aust Health Rev. 2019:43(3):314–22. CrossRef | PubMed

- 23. West R, Usher K, Buettner PG, Foster K, Stewart L. Indigenous Australians’ participation in pre-registration tertiary nursing courses: a mixed methods study. Contemp Nurse. 2013;46(1):123–34. CrossRef | PubMed

- 24. Gwynne K, Lincoln M. Developing the rural health workforce to improve Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health outcomes: a systematic review. Aust Health Rev. 2017;41(2):234–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 25. NSW Government. NSW TAFE statistical compendium 2013; 2013. [cited 2022 May 18] Available from: www.tafensw.edu.au/documents/60140/76288/TAFE-NSW-Statistical-Compendium-2013.pdf/1d03e5fe-6516-ce9e-4b67-a5600da0fb92

- 26. Gwynne K. New TAFE program for Aboriginal health students delivers near perfect completion rate. Australia: The Conversation; 2019 Mar 18 [cited 2022 May 18]. Available from: www.theconversation.com/new-tafe-program-for-aboriginal-health-care-students-sees-a-near-perfect-completion-rate-113270

- 27. Lai GC, Taylor EV, Haigh MM, Thompson SC. Factors affecting the retention of Indigenous Australians in the health workforce: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(5):914. CrossRef | PubMed

- 28. Gwynne K, Flaskas Y, O'Brien C, Jeffries T, McCowen D, Finlayson H, et al. Opportunistic screening to detect atrial fibrillation in Aboriginal adults in Australia. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e013576. CrossRef | PubMed

- 29. Gwynn J, Gwynne K, Rodrigues R, Taylor K, Wright D, Freeman B, et al. Atrial fibrillation in Indigenous Australians: a multisite screening study using a sing-lead ECG device in Aboriginal primary health settings. Heart Lung Circ. 2021;30(2):267–74. CrossRef | PubMed

- 30. Macniven R, Gwynn J, Fujimoto H, Hamilton S, Thompson S, Taylor K, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of opportunistic screening for atrial fibrillation among Aboriginal adults. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2019;43(4):313–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 31. Orchard J, Li J, Freedman B, Webster R, Salkeld G, Hespe C, Gallagher R, et al. Atrial fibrillation screen, management and guidelines-recommended therapy in rural primary care setting: a cross-sectional study and cost-effectiveness analysis of eHealth tools to support all stages of screening. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e017080. CrossRef | PubMed

- 32. Macpherson G. Roadmap to policy and practice change in screening for atrial fibrillation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Charles Perkins Centre Summer Scholar Seminar presentations: 16 Feb 2021. Available from authors.

- 33. Nahdi S, Skinner J, Freedman B, Gwynn J, Lochen ML, Neubeck L, Poppe K, et al. One size doesn’t fit all – a realist review of screening for asymptomatic atrial fibrillation in Indigenous communities in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and United States. European Heart Journal. 2021;42(Supplement 1):461. CrossRef

- 34. Cabaj M, Weaver L. Collective impact 3.0. An evolving framework for community change. Tamarack Institute. Community change series 2016. Ontario, Canada; Tamarack Institute; 2016 [cited May 18]. Available from: www.tamarackcommunity.ca/library/collective-impact-3.0-an-evolving-framework-for-community-change