Abstract

Objectives: Access in the early years to integrated community-based services that are flexible in their approach, holistic and culturally strong is a proven critical predictor of a child’s successful transition to school and lifelong education and employment outcomes, providing long-term wellbeing. Studies show that participation in maternal and child health (MCH) services in Victoria, Australia, improve health outcomes for children and families, particularly for Aboriginal families. Poorer health outcomes and lower participation rates for these families in MCH services suggest there is a need for an urgent review of the current service model. The purpose of this paper is to outline the Early Assessment Referral Links (EARL) concept that was trialled in the Glenelg Shire in Victoria, Australia (2009–2014) to improve the engagement of Aboriginal families in MCH services.

Methods: Development of EARL involved the core principles of appreciative inquiry to change existing patterns of conversation and give voice to new and diverse perspectives. A broad cross-section of the Aboriginal community and their early years health service providers were consulted and stakeholders recruited. Regular meetings between these stakeholders, in consultation with the Aboriginal community, were held to identify families that weren’t engaged in MCH services and also to identify families who required further assessment, intervention, referral and/or support, ideally from the preconception or antenatal periods. Outcome measures used to evaluate the EARL concept include stakeholder meetings data, numbers of referrals, and participation rates of women and children in MCH services.

Results: Participation of Aboriginal women and children in MCH services was consistently above the state average during the pilot period, and significant numbers of Aboriginal women and children were referred to EARL stakeholders and other health professionals via EARL referrals. Additionally, there were increases in Aboriginal children being breastfed, fully immunised and attending Early Start Kindergarten. Identification of Aboriginal women and children at risk of vulnerability also improved with a dramatic increase in referrals for family violence and child protection, and decreased episodes of out-of-home care (OoHC) for children.

Conclusions: Evaluation of pilot outcomes indicate that the EARL concept improved women and children’s access to and engagement with MCH services, and identified more families at risk of vulnerability than the traditional MCH service model, particularly for Aboriginal women and children.

Full text

Introduction

Maternal and child health (MCH) services in Victoria support families by providing 10 Key Ages and Stages (KAS) consultations between birth and 3.5 years, to monitor the health, growth and development of children. Although participation of Aboriginal families in MCH services has improved over time, MCH service data indicates lower participation rates for Aboriginal children compared with non-Aboriginal children at all 10 KAS consultations.1,2

This disparity is consistent with the broader inequality in health outcomes between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children at a national level.3 Despite measures by federal, state and local governments to improve the health outcomes of these children in Australia, data continues to show that almost half of all Australian Indigenous children are identified as vulnerable – twice the proportion of non-Indigenous children.3 Children are prone to vulnerability if their parents and family have limited capacity to care for and protect them effectively, and to provide for their long-term development and wellbeing.4

Key risk factors that contribute to making a child, young person and their family vulnerable include economic hardship – including related issues like unemployment and homelessness, family violence, alcohol and substance misuse, mental health problems, disability and parental history of abuse and neglect.4

This evidence suggests that a review of the effectiveness of the current MCH service model of care, particularly for Aboriginal families, is urgently needed. Models of care are widely used in health, providing a clear approach to the way services are delivered, optimally to encourage best practice care and services for an individual or population group as they advance through the stages of a condition, injury or event.5 The guiding principles of a model of care are that it is patient centric; flexible; considerate of equity of access; encourages integrated care and efficient utilisation of resources; supports safe, quality care for patients; has robust, standardised outcome measures and evaluation processes and regards innovative ways of organising and delivering care.6

To address this issue, the Glenelg Shire Council MCH team devised an approach to improve the identification of families with children from conception to 6 years, who are not engaged in MCH services, or who are at risk of vulnerability. The approach aimed to identify and reduce gaps within service delivery and to link those families into local services to provide a continuum of care, so a strong support system is in place before a baby is born. Importantly, access in the early years to integrated community-based services that are flexible in their approach, holistic and culturally strong is a proven critical predictor of a child’s successful transition to school and lifelong education and employment outcomes, providing long-term wellbeing. This is fundamental to Closing the Gap.4

This research was undertaken in the Glenelg Shire in south western Victoria, Australia, where there are an estimated 369 Aboriginal people, representing just under 2% of the population.7 Based on the first phase of a three-phase study, this article discusses the development and implementation of the EARL concept, and presents data reflecting the outcomes of the pilot study.

Methods

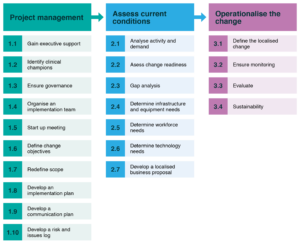

Development of the concept involved using the core principles of appreciative inquiry to change existing patterns of conversation and ways of relating, and to give voice to new and diverse perspectives to improve MCH services in this area.8 The steps involved in developing the EARL concept included consultation with the Aboriginal community, mapping practices and services, recruiting stakeholders, implementing the pilot and evaluating the pilot through outcome measures. Through this process, the researcher consulted with service providers who shared a common location (the early years setting), philosophy, vision and agreed principles for working with children 0–6 years and their families residing in the Glenelg Shire. All service providers that were approached elected to become EARL stakeholders, and reflected the diverse cross-section of organisations and multidisciplinary health professionals providing early years’ care that were involved in the delivery of, and referral to, MCH services locally. Figure 1 outlines the process followed to develop the EARL concept.

Figure 1. Development of the EARL concept (click to enlarge)

The pilot of the EARL concept was managed by a coordinator, who was the chair (the researcher CA). Glenelg Shire Council was the lead agency. The other stakeholders were a combination of multiple service providers and included local maternity and allied health services, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) (representing the Aboriginal community), Victorian Department of Education and Training (DET), Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and local government. The manager of each agency, or their nominated representative, agreed to meet on a regular basis to discuss children and young people at risk of vulnerability who would benefit from integrated support. EARL was funded through the Universal Maternal and Child Health program, which is provided through a partnership between the Victorian DET and local governments. The program’s funding for MCH services is based on the total number of children 0–6 years enrolled in the service. Each participating agency was self-funded to attend stakeholder meetings on a monthly basis.

The pilot of the EARL concept ran from 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2014. It started in Portland, Victoria, and branched out to incorporate whole-of-shire support. This resulted in Heywood EARL being established in March 2011 and Casterton EARL in April 2012.

Monthly meetings were conducted across the three locations – which stretch over a distance of 100km in the shire in far south western Victoria – and, where possible, were held at ACCHOs to encourage engagement of those stakeholders and highlight the group’s profile in Aboriginal communities. After signing consent to share their information, the cases of clients at risk of vulnerability were discussed by the group during meetings, or by a sub-group between meetings if more appropriate, resulting in referrals to other stakeholders as required.

The EARL concept was evaluated using a variety of data from numerous sources, including DET and Department of Education and Early Childhood Development annual reports.7,9-11 Also used were data from stakeholder meetings, rates of Aboriginal women and children referred to stakeholders, MCH services participation rates, number of children enrolled in Early Start Kindergarten, breastfeeding initiation and duration rates, immunisation rates, number of referrals to child protection and episodes of out-of-home care (OoHC).

The research has been approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Federation University (project number C17-024), the Human Research Ethics Committee of Department of Education and Training (project number 2014_002311), and the Department of Health and Human Services to use Client Relationship Information Systems and Integrated Reports Information System data. The Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation advised that approval from an Indigenous Human Research Ethics Committee was not required for this research.

Results

Portland adopted the EARL pilot for 5 years. During that time, there were 51 (85%) stakeholder monthly meetings and 9 months when no meeting was held. There were 17 stakeholders in Portland and an average stakeholder meeting attendance rate of 76%. Heywood was operational for 3.3 years. During this period, there were 36 (90%) monthly meetings and 4 months when no meeting was held. There were 12 stakeholders in Heywood and average stakeholder meeting attendance rate was 67%. Casterton operated for 2.25 years. During this time, there were 16 (59%) monthly meetings and 11 months when no meeting was held. This site involved nine stakeholders but only five (56%) regularly attended (the lowest attendance and lowest number of meetings of the three sites).

All Aboriginal families with children aged 0–6 years living in the Glenelg Shire during the pilot period who were approached by stakeholders to participate in the EARL pilot did so (2011: n = 52, 2013: n = 56).9 Data from the pilot shows there were a significant number of Aboriginal families referred to multiple EARL stakeholders, facilitating continuity of care. Among all women participants (n = 30), the highest proportion of women were referred to Aboriginal services, such as the ACCHOs (n = 27, 90%), Koori Maternity Services (n = 29, 97%) and Koori Education Support Services (n = 21, 70%). Almost half the women participating in the pilot were also referred to mainstream services providing maternity care (n = 14, 47%) and women were also referred to parent support (n = 12, 40%) and allied health services (n = 14, 47%), including counselling, diabetes educator, dietitian, drugs and alcohol services, early intervention, chronic disease services, exercise physiologist, occupational therapy, podiatry, speech pathology and youth worker. This indicates that women’s needs were likely to be identified and met by the EARL model of care.

During the pilot of the EARL concept, participation rates of Aboriginal children in the MCH service rose to rates above the state average. Before the pilot began, the MCH participation rate for Aboriginal children in Glenelg Shire (54%) was below the state average of 57%. By the second year of operation the participation rate was at its highest (89%), and the state average was at its lowest (50%) of the pilot period. The EARL participation rates continued to be higher than the state rate, even after the pilot had finished (see Table 1). After an initial increase to 89%, participation rates decreased over the subsequent years the pilot was running.

Table 1. Participation rates of Aboriginal children 0–6 years of age in maternal and child health (MCH) services in Glenelg Shire, 2008-09–2014-15

| Aboriginal children | 2008-09 | 2009-10a | 2010-11a | 2011-12a | 2012-13a | 2013-14a | 2014-15 |

| Children 0–6 years, Glenelg Shire (n) | 29 | 26 | 47 | 59 | 57 | 61 | 65 |

| Participation rate: children 0–6 years, Glenelg Shire MCH service (%) |

53.7 | 81.3 | 88.7 | 85.5 | 72.2 | 73.5 | 62.5 |

| Participation rate: children 0–6 years, state of Victoria MCH service (%) |

56.7 | 60.1 | 50 | 59.8 | 55.1 | 53.9 | 55.5 |

a Participation rates during the EARL pilot period

Sources: Victoria State Government, Department of Education and Training. Maternal & Child Health Services annual reports7,9-11

In conjunction with higher participation rates, the referral of Aboriginal children to EARL stakeholders increased significantly during the pilot period. The highest number of referrals were to nursery equipment (n = 56, 100% of all children in the pilot)12 and the Dolly Parton Imagination Library13 (n = 56, 100%) programs. Additionally, nearly all children in the pilot were referred to allied health programs (n = 48, 86%), such as dietetics, speech pathology, dentistry, ophthalmology, physiotherapy and audiology. More than one-third of the children in the pilot were referred to a supported playgroup (n = 21, 38%) – a favourable statistic considering there was only one supported playgroup in the Glenelg Shire.

Early Start Kindergarten provides up to 15 hours per week of free or low-cost kindergarten to eligible children aged 3 years (including Aboriginal children or those who have had contact with child protection services).14 During the EARL pilot, there was a 100% participation rate of eligible Aboriginal children in Early Start Kindergarten, all of whom were identified and referred to the program by EARL stakeholders (overall state enrolments to Early Start Kindergarten ranged from 33–51% during the same period).

There is strong evidence that breastfeeding gives babies the best start for a healthy life and has health and wellbeing benefits for both the mother and child.15-17 During the EARL pilot, there was an increase in the percentage of Aboriginal mothers initiating breastfeeding from 67% before the pilot to 100% 3 years into the pilot, and breastfeeding rates at 6 months increased from 17% before the pilot to 76% 3 years into the pilot (Table 2). Even after the pilot this rate remained high at 54% (national rates for initiating breastfeeding are around 96%, which fall dramatically to around 9% at six months duration).16,17

Table 2. Breastfeeding rates of mothers of Aboriginal children in Glenelg Shire, 2008-09–2014-15

| Aboriginal children | 2008-09 | 2009-10a | 2010-11a | 2011-12a | 2012-13a | 2013-14a | 2014-15 |

| Births (n) | 6 | 19 | 22 | 17 | 17 | 12 | 24 |

| Breastfed at birth (%) | 67 | 89 | 95 | 100 | 94 | 92 | 84 |

| Breastfed at 2 weeks (%) | 50 | 84 | 86 | 100 | 88 | 92 | 79 |

| Breastfed at 3 months (%) | 33 | 79 | 81 | 88 | 82 | 83 | 63 |

| Breastfed at 6 months (%) | 17 | 63 | 64 | 76 | 71 | 67 | 54 |

a Participation rates during the EARL pilot period

Sources: Victoria State Government, Department of Education and Training. Maternal & Child Health Services annual reports9-11

Studies show that immunisation is the most effective way of protecting children against previously common life-threatening infections.18,19 During the EARL pilot period, there was an increase in the percentage of Aboriginal children fully immunised in the Glenelg Shire from 84% before the pilot to 97% by the fourth year into the pilot (state immunisation rates in the same period were 85% and 90% respectively) (Table 3). Although a moderate increase, the Glenelg Shire consistently achieved higher rates of immunisation compared with those across the state.

Table 3. Immunisation rates of Aboriginal children, 2008-09–2014-15

| Aboriginal children | 2008-09 | 2009-10a | 2010-11a | 2011-12a | 2012-13a | 2013-14a | 2014-15 |

| Births: Glenelg Shire (n) | 6 | 19 | 22 | 17 | 17 | 12 | 24 |

| Fully immunised 0–6 year olds: Glenelg Shire (%) |

83.57 | 86.75 | 91.67 | 88.50 | 97.44 | 94.87 | 83.57 |

| Fully immunised 0–6 year olds: state of Victoria (%) |

84.98 | 85.94 | 87.64 | 87.63 | 90.14 | 90.05 | 89.28 |

a Participation rates during the EARL pilot period

Sources: Victoria State Government, Department of Education and Training. Maternal & Child Health Services annual reports10,12

Family violence significantly affects the way a woman raises her child, which ultimately affects the child’s development.20-22 In the first year of the EARL pilot, there was a dramatic increase in the number of Aboriginal mothers/families referred to services to assist with family violence, from zero referrals before the pilot to 15 referrals within a year.7 DET data was not available to ascertain referral rates for the rest of the pilot period.

Child protection services are provided by the DHHS and aim to ensure children and young people receive services to deal with the impact of abuse and neglect on their wellbeing and development.23 There was a significant increase in referrals of Aboriginal children residing in Glenelg Shire to child protection services, from three referrals in 2008, the year prior to the EARL pilot, to 27 in the first year of the pilot. This trend remained the year after the pilot was complete, indicating the extent of referrals through EARL.

OoHC services look after children and young people in cases of family conflict or if there is a significant risk of harm or abuse in the family home.14 After a small initial increase, there was a substantial decrease in the number of episodes of OoHC for Aboriginal children 0–6 years in Glenelg Shire during the EARL pilot period – from 38% of Aboriginal children 0–6 years in the shire being in OoHC in the year before the pilot to 4.54% in the second year of operation. This compared with a national rate of Aboriginal children in OoHC of 5.17%.24

Discussion

Data collected in the pilot phase of the study demonstrates stakeholders’ engagement with the EARL model. The monthly EARL meetings were well attended in all three sites with the exception of Casterton, which could have been due to accessibility (Casterton is more than 100 km from Portland and 70 km from Heywood). The use of Skype in meetings was initiated in the last 7 months of the pilot period, which improved the engagement of stakeholders from other sites at the meetings held in Casterton.

Overall, the EARL concept proved successful in engaging Aboriginal families with MCH services, as shown by the rise in participation rates (consistently above the state average) and the significant number of referrals to EARL stakeholders and other healthcare services as a result of the monthly EARL stakeholder meetings. Additionally, the EARL concept may have also contributed to improving the health outcomes of Aboriginal families and children in the Glenelg Shire as evidenced by the increase in rates in breastfeeding and fully immunised children. The identification of Aboriginal women and children at risk of harm also improved, with dramatic increases in referrals for family violence and referrals to child protection services and an overall decrease in the number of episodes of OoHC for children. The sharp increase in referrals for family violence in the first year of the pilot and lack of subsequent data highlights a need for further research in this area.

Higher referrals to child protection suggest that either stakeholders became more vigilant identifying those at risk or there were more cases overall. Integral to this result is the inclusion of a DHHS family service worker among the EARL stakeholders.

The EARL model of care

The EARL concept is being developed by the researcher into a new model of care, which is evidence based and strengths based, with a holistic, wrap-around-the-child service approach, using the Continuum of Need model25 to monitor the risk of vulnerability/need. The model’s framework is based on a co-design process that draws on the expertise of service stakeholders to develop effective coordination, collaboration and communication in line with the aims of the Victoria State Government’s Roadmap for reform for child and family services.26 Co-design allows stakeholders to develop new insights and solutions collaboratively to promote effective engagement with MCH services on an equal basis, through creative and often narrative-based activities. Further, the co-design approach facilitates a multidisciplinary team around the child through information sharing and shared learning. The EARL Model of Care encourages an open network inclusive of organisations working with families and children across the stages of life, from preconception to school. Most importantly, the EARL model of care allows the integration of traditional Aboriginal child-rearing practices with standardised Western healthcare values, beliefs and practices through a guided mastery approach, shared knowledge, yarning, capacity building, mutual trust and connection.

Conclusion

To address the disparity in health outcomes between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children in Australia, the EARL concept was developed and implemented in the Glenelg Shire in Victoria, Australia. Evaluation of outcome measures, including participation and referral rates during the pilot period suggest that EARL improved the engagement of Aboriginal families with MCH services. Additionally, the EARL concept was able to identify more families at risk of family violence than the current MCH service model. Further research is needed to develop the concept into a model of care to better understand the current barriers MCH nurses face in identifying “at risk” families.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, not commissioned.

Copyright:

© 2020 Austin and Arabena. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Department of Education and Training. Maternal and child health service annual report 2012–2013. Melbourne: State Government of Victoria; 2014 [cited 2020 Jul 14]. Available from: www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/childhood/providers/support/Victoria%20Statewide%20Report.pdf

- 2. Fenton C, Jones L. Achieving cultural sensitivity in Aboriginal maternity care. Int J Health Sci. 2015;3(1):23–38. CrossRef

- 3. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2015. Canberra: AIHW; 2015 [cited 2020 Jul 14]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/584073f7-041e-4818-9419-39f5a060b1aa/18175.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- 4. Victorian Auditor-General’s Office. Annual Report 2015–16. Melbourne: VAGO; 2016 [cited 2020 Jul 14]. Available from: www.data.vic.gov.au/data/dataset/vago-annual-report-2015-16

- 5. Agency for Clinical Innovation. Understanding the process to implement a model of care: an ACI framework. Sydney: NSW Government; 2013 [cited 2020 Jul 11]. Available from: www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/194715/HS13-036_ImplementationFramework_D5-ck2.pdf

- 6. Government of Western Australia Department of Health. Models of care. Perth, WA: State of Western Australia; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 21]. Available from: ww2.health.wa.gov.au/Articles/J_M/Models-of-care

- 7. Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. Annual report 2009–2010. Melbourne: State of Victoria; 2010 [cited 2020 Jul 14]. Available from: www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/about/department/200910deecdannualreport.pdf

- 8. Sharp S, Dewar B, Barrie K. How appreciative inquiry creates change – theory in practice from health and social care in Scotland. Action Res. 2018;16(2):223–43. CrossRef

- 9. Victoria State Government, Department of Education and Training. Maternal & Child Health Services annual reports 2010-2016. Melbourne; health.vic; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 22]. Available from: www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/publications/researchandreports/?q=maternal&pn=1&ps=10&s=relevance&i=&f=&n=&e=&a=&ac=&df=&dt=&l=&lq=

- 10. Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. Annual report 2009–2010. Melbourne: State of Victoria; 2010 [cited 2020 Jul 14]. Available from: www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/about/department/200910deecdannualreport.pdf

- 11. Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. Annual report 2008–2009. Melbourne: Department of Education and Early Childhood Development; 2009 [cited 2020 Jul 29]. Available from: www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/about/department/200809deecdannualreport.pdf

- 12. Victoria State Government. Health and Human Services. Nursery equipment program guidelines. Melbourne: Victoria State Government; Reissued 2019 [cited 2020 Jul 21]. Available from: www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/publications/policiesandguidelines/nursery-equipment-program-guidelines

- 13. United Way Glenelg. Dolly Parton Imagination Library [cited 2020 Jul 22]. Available from: www.unitedwayglenelg.com.au/causes/dolly-parton-imagination-library/

- 14. Victoria State Government. Health.vic. Melbourne: Victoria State Government; 2017. Maternal and Child Health Service [cited 2020 Jul 21]. Available from: www2.health.vic.gov.au/primary-and-community-health/maternal-child-health

- 15. de Jager E, Skouteris H, Broadbent J, Amir L, Mellor K. Psychosocial correlates of exclusive breastfeeding: a systematic review. Midwifery. 2013;29(5):506–18. CrossRef | PubMed

- 16. Forster D, McLachlan H, Lumley J, Beanland C, Waldenstrom U, Amir L. Two mid-pregnancy interventions to increase the initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a randomised controlled trial. Birth. 2004;31(3):45–50. CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. National Health and Medical Research Council. Infant feeding guidelines. Canberra: NHMRC; 2012 [cited 2018 July 25]. Available from: www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines-publications/n56

- 18. Hull B, Deeks S, McIntyre P. The Australian childhood immunisation register – a model for universal immunisation registers? Vaccine. 2009;27(37):5054–60. CrossRef | PubMed

- 19. Pearce A, Marshall H, Bedford H, Lynch J. Barriers to childhood immunisation: findings from the longitudinal study of Australian children. Vaccine. 2015;33(29):3377–83. CrossRef | PubMed

- 20. Holden G, Ritchie K. Linking extreme marital discord, child rearing and child behaviour problems: evidence from battered women. Child Dev. 1991;62(2):311–27. CrossRef | PubMed

- 21. Levendosky A, Graham-Bermann S. Parenting in battered women: the effects of domestic violence on women and their children. J Fam Violence. 2001;16(2):171–92. CrossRef

- 22. McCloskey L, Figueredo A, Koss M. The effects of systematic family violence on children’s mental health. Child Dev. 1995;66(5):1239–61. CrossRef | PubMed

- 23. Bromfield L, Holzer P.A national approach for child protection: Project report. Canberra: Australian Institute of Family Studies; 2008 [cited 2020 Jul 14]. Available from: aifs.gov.au/cfca/sites/default/files/publication-documents/cdsmac.pdf

- 24. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National framework for protecting Australia’s children 2009–2020: technical paper on operational definitions and data issues for key national indicators. Canberra: AIHW; 2013 [cited 2020 Jul 21]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/bc891123-9d00-40a5-81a4-772ae663a071/15967.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- 25. Department of Education and Training. Continuum of need service response indicator tool. Melbourne: Department of Education and Training; 2015 [cited 2020 Jul 29]. Available from: www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/support/diversity/eal/continuum/Pages/userguide.aspx

- 26. Department of Health and Human Services. Roadmap for reform: strong families, safe children. Melbourne: State of Victoria; 2016 [cited 2020 Jul 14]. Available from: engage.vic.gov.au/download_file/8422/1560