Abstract

Objectives and importance of study: Low program completion rates can undermine the public health impact of even the most effective program. Participant experiences with lifestyle programs are not well reported, but are important for program improvement and retention. The purpose of this study was to understand participant perceptions of the Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service (GHS), a 6-month telephone-based health coaching program to promote lifestyle change. We were particularly interested in participants’ initial expectations, their actual experience and, for those who did not complete the program, what influenced their withdrawal.

Study type: The study included qualitative semistructured interviews and a quantitative sociodemographic survey.

Methods: A random sample of GHS participants (n = 59) was recruited to take part in semistructured interviews about their perceptions and experiences of the coaching program. Researchers conducted independent thematic analysis of the interview transcripts. Sociodemographic details were obtained from a quantitative survey of all GHS participants.

Results: Participants expected that coaching would provide support, information and motivation, and would hold them accountable. Coach support was the most valued aspect of the participants’ experience. Despite high attrition rates, participants were mostly positive about their coaching experience. Service structure or individual circumstances, rather than the program itself, were the main reasons for withdrawal.

Discussion: A positive coaching experience was underpinned by good participant–coach rapport, which facilitated participant adherence and motivation to achieve their goals and complete the program. It is possible that participants who start to achieve their goals are motivated to continue with the program, and that their motivation moves from relying on their coach to being more intrinsically motivated. Reasons for high attrition provide insights into the coaching structure and process, and suggest that ensuring an individualised coaching approach and flexibility with follow-up calls (including alternative communication methods) are changes that could be used to improve practice and retain more participants for the duration of the program.

Conclusions: Notwithstanding high attrition rates, participants were mostly positive about their coaching experience. Barriers to participants completing the program could be used to shape service redesign.

Full text

Introduction

Overweight and obesity in adults are well-established risk factors for a number of chronic diseases, and rates of overweight and obesity are rising.1 As part of a mix of strategies to address this growing burden, the state government of New South Wales (NSW), Australia, launched a lifestyle change program, the Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service (GHS) in 2009. The program offers 10 free individually tailored telephone coaching calls, provided by university-qualified health coaches to adults older than 18 years. It is based on evidence of the effectiveness of telephone-based behaviour change interventions targeting physical inactivity and unhealthy eating, which are major risk factors for overweight and obesity.2-4 Participants are provided with evidence based printed material that is consistent with the objectives of supporting adults to make sustained improvements in healthy eating, physical activity, and achieving or maintaining a healthy weight.

As a population-wide program, the GHS has been effective in improving unhealthy lifestyle habits and reducing the weight and waist circumference of participants over 6 months5 and 12 months.6 Despite its success, coaching program attrition rates are high, and 74% of participants withdraw before completing the GHS.5 Other real-world weight-loss interventions experience similar attrition rates.7,8 Client views, expectations and values are central to effective coaching, and have a direct bearing on coaching progress.9

Current evidence relating to factors influencing participant expectations, experiences, completion rates and attrition in lifestyle modification programs is sparse and largely limited to research contexts of randomised trials or efficacy trials.10,11 Previous research has identified that program characteristics (such as frequency of contact), healthy behaviour changes made during the program, the participant’s health status, lack of motivation, and life events during program engagement can all influence participant retention and withdrawal.12-14

It is important to understand the contributing factors that make a health coaching program appealing and engaging for some, but not for others. Elaborating on the reasons for attrition from the GHS will inform ongoing service improvement and future ‘real-world’ programs. The primary purpose of this study was to better understand participants’ attitudes and experiences of a telephone-based health-coaching lifestyle program. Specifically, we examined participant expectations before starting coaching, their perceptions of the coaching experience and, for those who withdrew from the coaching program, the factors that influenced their withdrawal.

Methods

The study was approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number 02-2009/11570).

Participants and sampling

Elements of the GHS, including evaluation methods and participant recruitment, have previously been reported.4 GHS participants who consented to be contacted for evaluation were eligible for this study if they had either completed coaching or withdrew actively (reasons for withdrawing provided) or passively (reasons for withdrawing unknown) from coaching, between 1 May and 31 August 2012.

This study sampled from two subgroups of GHS participants: those who had completed the GHS program and those who had withdrawn from the program. A sampling frame stratified by these two subgroups was created to randomly draw a sample of 66 participants who completed coaching and 80 participants who withdrew from coaching (45 who passively withdrew from coaching and 35 who actively withdrew). Because considerably fewer males use the GHS than females15, consistent with weight-loss interventions in health services and commercial programs for weight loss16, males were oversampled to attempt a gender balance in participant perceptions. Aboriginal participants were also oversampled because, as a key target population, it was considered necessary to ensure their views were well represented in the study (however, no comparative analysis was conducted). A separate study has described how formative research and a partnership process with Aboriginal communities guided the development and refinement of the GHS for Aboriginal participants.17,18 Prospective participants of the current study were contacted by telephone and invited to take part in the interview.

Quantitative component

Participant sociodemographic information was routinely collected by GHS health coaches.15

Qualitative component

A semistructured interview guide was developed, reviewed and refined to align with the research questions and guide the interview process. The interview guide facilitated consistency between interviewers, providing comparable data while allowing participants to express their views and opinions. Collectively, the interview questions aimed to draw out participant perceptions and expectations of coaching before starting coaching; their overall impression and perceived value of coaching calls received, including the interaction with their coach; and the factors influencing withdrawal from the coaching program. Two research staff trained in telephone interviews used reflective listening to explore the perceptions and experiences of participants during interviews, which took, on average, 20 minutes to complete.

Data analysis

Participant responses were de-identified before analysis to maintain confidentiality. Quantitative data were entered into EpiData (Odense, Denmark: EpiData Association; Version 3.1) and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp), and descriptive analysis was undertaken. Thematic analysis of qualitative data was undertaken independently by three researchers who generated initial codes across the dataset, and searched for common themes, collating these into potential themes.19 Two researchers analysed each set of interviews: participants who had completed coaching and participants who had withdrawn from coaching. The researchers collectively considered potential themes, and disagreements were reviewed and discussed until agreement was reached.

Results

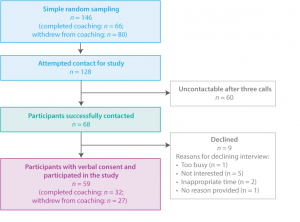

Interviews with consenting participants took place in September and October 2012. Thematic analysis defined the final number of participants interviewed, as interviews were conducted until a saturation of themes20 was reached for those who completed coaching (n = 32) and for those who withdrew from coaching (n = 27) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of study participants

The sociodemographic characteristics of all participants enrolled in the GHS during 2012, and of study participants, are presented in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between all GHS coaching participants and those who were interviewed, other than for employment and Aboriginal status. A higher proportion of participants interviewed (59.3%) were not in paid employment compared with all coaching participants (41.7%; p = 0.007) and 15.3% of participants interviewed were Aboriginal compared with 5.4% of all coaching participants (p = 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline sociodemographic characteristics of all GHS coaching participants compared with study participants

| Characteristic | Category | All GHS participants (2012)a (N = 2448) |

Interviewed participants (N = 59) |

p-value | ||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Gender | Female | 1731 | 70.7 | 37 | 62.7 | NS |

| Male | 717 | 29.3 | 22 | 37.3 | ||

| Age (years) | 18–49 | 1332 | 54.4 | 28 | 47.5 | NS |

| 50 and older | 1115 | 45.6 | 31 | 52.5 | ||

| Education | Secondary education | 1088 | 44.5 | 30 | 50.8 | NS |

| Tertiary education | 1355 | 55.5 | 29 | 49.2 | ||

| Employment | Employed | 1416 | 57.9 | 24 | 40.7 | 0.007 |

| Not employed | 1029 | 42.1 | 35 | 59.3 | ||

| Language spoken at home | English | 2251 | 92.0 | 58 | 98.3 | NS |

| Other | 197 | 8.0 | 1 | 1.7 | ||

| Aboriginal status | Non-Aboriginal | 2308 | 94.3 | 50 | 84.7 | 0.001 |

| Aboriginal | 139 | 5.7 | 9 | 15.3 | ||

| Region | Major cities | 1431 | 58.7 | 27 | 45.8 | NS |

| Other | 1007 | 41.3 | 32 | 54.2 | ||

| SEIFA | Least disadvantaged | 1129 | 46.3 | 36 | 61.0 | NS |

| Most disadvantaged | 1311 | 53.7 | 23 | 39.0 | ||

GHS = Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service; NS = not significant; SEIFA = Socio-Economic Index For Areas

a Discrepancies in number of participants for some variables is due to missing data.

Note: The p-values represent the results from the chi-square analysis, which compared interviewed participants with the rest of the GHS participants for 2012.

Of 27 participants who withdrew from coaching, 33.3% (n = 9) withdrew during weeks 0–1 (before starting coaching), 55.5% (n = 15) withdrew during weeks 2–9, and 11.1% (n = 3) withdrew during weeks 12–23 (data not shown).

Participants expected support and advice

Participant expectations before starting the coaching program varied, ranging from having no expectations or being unsure of what to expect, to a small number who were sceptical of what was on offer. For some, their experience with the GHS coaching program met or exceeded expectations.

… started the service because I was extremely overweight. If you receive encouragement, you tend to do it, and you knew they would ring to check in. Once the weight starts to come off, you feel good, which reinforces you to lose more. Just thought I will give it a go, and if it does not work out I was just going to say I was not interested … but my coach was great. (78-year-old female participant, completed coaching)

A strongly voiced theme regarding expectations of the GHS was that the coaching program would provide both support and information. Embedded within this expectation was the belief of these participants that the coaching program would help to provide motivation for them to achieve their goals. For some, this meant that they hoped to find motivation; for others, it meant that they hoped a third party would help them to maintain motivation and act as someone to be accountable to in some way.

I had a fair idea of what it was about … getting you back on track, healthy eating … I needed the kick start because I had lost weight in the past, 70kg, but it was slowly creeping back up and I had had enough. I tried Get Healthy because I needed someone to get me back into the right mindset, and having someone calling me regularly would also mean accountability. (60-year-old female, completed coaching)

Half of those interviewed anticipated that they would receive weight loss support and advice, and would achieve weight loss. A few wanted to increase their fitness and receive physical activity advice, and a very small number hoped to reduce their waist circumference. A general improvement in health, as well as a better lifestyle, was expected by some.

The role of the coach to facilitate change

According to almost half of participants interviewed, the most valuable aspect of the coaching program was the support they received from their coach. They reported finding the reassurance and encouragement provided by their coach useful. Additionally, being answerable and accountable to someone to make changes, as well as having a neutral person to talk to, were perceived as valuable. The relationship that participants developed with their coach was integral to receiving the support necessary to achieve goals, and regular contact with the coach was perceived as important to stay on track and remain motivated.

… having the coach ring you to give you a push. (30-year-old female, passively withdrew)

… the motivation of getting a phone call helped to keep me on track. (68-year-old male, completed coaching)

… felt the health coach was sincerely interested in me. (66-year-old female, completed coaching)

The ability of the coach to individually tailor the coaching approach, as well as being able to take part in the program from home (as it is a telephone-based service), were perceived as beneficial.

… was tailored to my own needs – for someone who didn’t want face-to-face. (41-year-old female, actively withdrew)

… one-on-one help, not having different people so I had a sense of familiarity with my coach so I felt comfortable. (31-year-old female, completed coaching)

A few participants, however, mentioned a preference for face-to-face coaching.

Most participants found their coach to be knowledgeable and professional. Participants perceived this to be beneficial, along with the information booklets, advice and information received. Dietary advice, in particular, was mentioned by the majority as worthwhile, while physical activity recommendations were only mentioned by one participant.

… the coach was helpful with snack options – lower energy options – and helped me deal with barriers when I started putting on weight in the beginning. (46-year-old female, completed coaching)

Opinion regarding the least positive aspects of the GHS generally fell into two areas: limitations relating to the service structure and limitations relating to the coach. One participant felt that their coach was too young and not in touch with issues specific to them. Another commented that their coach lacked enthusiasm, while another wanted to change coaches but did not feel able to do so without repercussions. Limitations of the GHS structure included feeling that advice needed to be more specific and that the program was too short.

… felt that my coach did not have much knowledge in how to individualise for each person, as we are all different. (64-year-old male, completed coaching)

… felt brushed off at the end. The time the program runs should be reflective of weight loss. Maybe if you need to lose 5 kg you need 3 months, but if you need to lose 30 kg like me, maybe you need a year. (34-year-old female, completed coaching)

Although not provided as a reason for withdrawing (but a statement on the structure of the GHS program), a comment from a 70-year-old male participant who withdrew passively and was now participating in a different health program provided an opinion worth considering: “preferred how they (the other health program) are more assertive, more structured and provide more advice on how to reach goals”.

Barriers to completing coaching

The reasons for withdrawing from the coaching program broadly fell into two groups: those relating to the internal structure of the program, and external reasons relating to the participant rather than the coaching program. Internal reasons for passive withdrawal included the timing of calls, where participants missed calls due to work or travel commitments, or being too busy. Dissatisfaction with the program was cited by a few participants, mainly by those who withdrew passively, with some comments specifically relating to the coach and others relating to the coaching program as a whole.

… lost contact with my coach then lost the incentive to continue. (70-year-old female, passively withdrew)

… busy at the time – long work hours. Didn’t always have time to take the calls. (51-year-old male, passively withdrew)

… coaching was too regimented and scripted. (36-year-old female, passively withdrew)

… the service was a bit distant and I did not connect with the service. (35-year-old female, passively withdrew)

External reasons were provided by more participants who withdrew actively than passively, with personal or family-related illness or injury cited as the primary reasons for leaving the coaching program. A few participants actively withdrew because they were not willing to change their behaviour or felt that they did not need assistance.

… didn’t need the coaching service. Get Healthy gave me reassurance that I was on the right track. (74-year-old female, actively withdrew)

… too old to change my eating habits. (69-year-old male, actively withdrew)

The results indicate that participants were not aware of the ability to re-enrol or recommence with the GHS coaching program.

Discussion

This study found that participant expectations of the coaching program were aligned with the GHS aims. Participants who completed coaching valued regular contact and support from their coach and the information and advice provided. From a limited pool of qualitative studies, participant perceptions and experience of coaches to provide support and monitoring, build rapport and provide nonjudgemental advice were identified as important in achieving lifestyle modifications.11,12,21 As with a real-world diabetic telephone health coaching program22, the majority of participants reported positive GHS experiences (satisfaction), which helped them to achieve their health-related goals. Maintaining self-monitoring and motivation were identified as barriers to weight loss and physical activity23, and the positive experiences of most participants were underpinned by coaches’ knowledge and professionalism. The rapport developed between coaches and participants facilitated adherence and motivation to complete the coaching program.

A key factor that may influence program completion is the behaviour-change process, where progression towards a goal becomes its own positive regulating cycle. Weight loss was the primary reason for enrolling in coaching and participants valued their coaches’ support to achieve their weight-related goals. This is consistent with research of predictors of weight loss and participant retention in a community-based weight management program, which found that modifiable factors such as staff interactions were predictive of significant weight loss.10 Potentially, greater weight loss increased participants’ confidence to achieve their goals, increasing the likelihood of feeling positive about the program, immersing themselves in the process, and ultimately completing the program, in line with evidence that those who set more ambitious GHS goals achieved more weight loss.24 Equally, when participants start achieving their goals, their motivation to continue with the program may shift from needing extrinsic motivation (relying on their coach) to being more intrinsically motivated.12,25

The individually tailored nature of the coaching program, which encourages positive coach–participant rapport and constructive goal setting, was perceived as positive. A contrary view was that the coach did not sufficiently tailor the program, or that the coach or program was not assertive or structured enough to facilitate goal attainment. Coaching is comprised of diverse goal-oriented approaches, including being directive or nondirective26, and individual participants are unique in their responses to different approaches. Creating a balance between a prescriptive, structured approach and one that is more fluid and reflective might strengthen the potential for each participant to reach the most effective outcome. This is supported by a GHS coaching review audit, which found that there is an opportunity for preventive health coaching to be more directive by maximising goal accountability, referencing evidence based materials more often, providing more information and education, and managing the coaching process to stimulate action.27

Combinations of internal (system-level) as well as external (participant-level) factors were reported in this study to lead to high attrition. System-level reasons included the timing of calls, where participants missed calls because of other commitments. Although there is flexibility for coaches to contact participants at different times of the day, participants withdrew or were automatically terminated from the program when they could not be contacted, emphasising dependence on one means of communication. It has been recommended that complementing telephone-based coaching with other communication platforms (such as text messaging or web-based media) may facilitate coaching adherence and completion, and that digital interactive methods of intervention deserve further study.23

Participant-level attrition factors included personal or family-related illnesses, feeling unwilling to change behaviour, and feeling that they no longer required assistance. Because the GHS is free, financial factors were not highlighted as a barrier to participation28; however, both health- and time-related factors were attributed to participant withdrawal, as also identified in other lifestyle interventions.13,28 As illness and injury are unavoidable, participants can re-enrol in GHS coaching at any time. Participant awareness of this option, however, was not apparent from the interviews. It would help to clearly reinforce this information, or, alternatively, implement proactive reintroduction calls to participants who withdraw before program completion.

A small number of participants were dissatisfied with the service, and more specifically with their coach. The reasons provided, while important, were mostly specific to individual situations and cannot be generalised. A lack of confidence in the coaches’ ability or professionalism has been cited as a barrier to behaviour change12, but was not evident from this study. The minimal dissatisfaction highlights that coaching is not necessarily appropriate for everyone. It can be beneficial for some but not others, which also reflects the inherent heterogeneous characteristics of GHS users.15

Limitations of this study include reliance on self-report, which may be subject to recall bias. We attempted to minimise this risk by restricting interviews to participants who had either completed or withdrawn from coaching during the 3 months preceding the study. A number of participants were unable to be contacted, and this group of participants may have differed in some way from those who participated in the study.

Conclusion and practice implications

Highlighting participant perceptions provides a better understanding of the behaviour change process during a free telephone-based lifestyle coaching program from the users’ perspective. Participant expectations were generally consistent with GHS objectives, and the majority of participants were satisfied with their experience. The participant–coach rapport was highly valued and facilitated participant adherence and motivation to complete the program and achieve their weight-related goals.

High attrition could potentially be influenced by service redesign. Potential areas of change may include individualising the service using effective goal setting, allowing a more directive coaching approach, ensuring increased flexibility in follow-up call timing to maximise participant contact, and using an alternative mode of communication such as text messaging or emails to arrange follow-up calls. It is important to actively advise participants about the procedures leading to automatic termination from a service, and to confirm how they can re-engage. There is also scope for ongoing satisfaction surveys and feedback processes, allowing participants to feel confident and assertive in providing feedback about their coaching experience.

Acknowledgements

We thank Melissa Gwizd and Belinda von Hofe for conducting the interviews and for their assistance with thematic coding, and Caroline Sharpe for assisting with the literature review that informed the study development. We also thank the GHS participants and the NSW Ministry of Health, which funds the GHS and provided funding to the University of Sydney to evaluate the GHS.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, not commissioned

Copyright:

© 2018 McGill et al. This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian health survey: first results, 2011–12. Canberra: ABS; 2012 [cited 2017 Oct 22]. Available from: www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/1680ECA402368CCFCA257AC90015AA4E/$File/4364.0.55.001.pdf

- 2. Goode AD, Reeves MM, Eakin EG. Telephone-delivered interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: an updated systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(1):81–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 3. Eakin EG, Lawler SP, Vandelanotte C, Owen N. Telephone interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5):419–34. CrossRef | PubMed

- 4. O'Hara BJ, Bauman AE, Eakin EG, King L, Haas M, Allman-Farinelli M, et al. Evaluation framework for translational research: case study of Australia's Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service®. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(3):380–9. CrossRef | PubMed

- 5. O'Hara BJ, Phongsavan P, Venugopal K, Eakin EG, Eggins D, Caterson H, et al. Effectiveness of Australia's Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service: translational research with population wide impact. Prev Med. 2012;55(4):292–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 6. O'Hara BJ, Phongsavan P, Eakin EG, Develin E, Smith J, Greenaway M, et al. Effectiveness of Australia's Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service: maintenance of self-reported anthropometric and behavioural changes after program completion. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:175. CrossRef | PubMed

- 7. Graffagnino CL, Falko JM, Londe M, Schaumburg J, Hyek MF, Shaffer LE, et al. Effect of a community‐based weight management program on weight loss and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Obesity. 2006;14(2):280–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 8. Moroshko I, Brennan L, O'Brien P. Predictors of dropout in weight loss interventions: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2011;12(11):912–34. CrossRef | PubMed

- 9. Stober DR, Wildflower L, Drake D. Evidence-based practice: a potential approach for effective coaching. Int J Evid Based Coaching Mentoring. 2006;4(1):1–8. Article

- 10. Abildso C, Zizzi S, Fitzpatrick S. Predictors of clinically significant weight loss and participant retention in an insurance-sponsored community-based weight management program. Health Promot Pract. 2012;14(4):580–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Hardcastle S, Hagger M. "You can't do it on your own": experiences of a motivational interviewing intervention on physical activity and dietary behaviour. Psychol Sport Ex. 2011;12:314–23. CrossRef

- 12. Chan R, Lok K, Sea M, Woo J. Clients' experiences of a community based lifestyle modification program: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:2608–22. CrossRef | PubMed

- 13. Groeneveld I, Proper K, van der Beek A, Hildebrandt V, van Mechelen W. Factors associated with non-participation and drop-out in lifestyle intervention for workers with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:80. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. Toth-Capelli K, Brawer R, Plumb J, Daskalakis C. Stage of change and other predictors of participant retention in a behavioral weight management program in primary care. Health Promotion Practice. 2012;14(3):441–50. CrossRef | PubMed

- 15. O'Hara BJ, Phongsavan P, Venugopal K, Bauman AE. Characteristics of participants in Australia's Get Healthy telephone-based lifestyle information and coaching service: reaching disadvantaged communities and those most at need. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(6):1097–106. CrossRef | PubMed

- 16. Robertson C, Archibald D, Avenell A, Douglas F, Hoddinott P, Boyers D, et al. Systematic reviews of and integrated report on the quantitative, qualitative and economic evidence base for the management of obesity in men. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18(35). CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. Cultural Partners Australia, Origin Communications. Exploration of the Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service resources and processes with Aboriginal People. Sydney: NSW Department of Health Centre for Health Advancement; 2010. Copy available from author.

- 18. Cultural and Indigenous Research Centre Australia. Get Healthy Service Aboriginal appropriateness study: final report. Sydney: CIRCA; 2015. Copy available from author.

- 19. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. CrossRef

- 20. Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. CrossRef

- 21. Liddy C, Johnston S, Irving H, Nash K, Ward N. Improving awareness, accountability, and access through health coaching: qualitative study of patients’ perspectives. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61(3):e158–64. PubMed

- 22. Adams SR, Goler NC, Sanna RS, Boccio M, Bellamy DJ, Brown SD, et al. Patient satisfaction and perceived success with a telephonic health coaching program: the Natural Experiments for Translation in Diabetes (NEXT-D) Study, Northern California, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E179. CrossRef | PubMed

- 23. Venditti EM, Wylie-Rosett J, Delahanty LM, Mele L, Hoskin MA, Edelstein SL, et al. Short and long-term lifestyle coaching approaches used to address diverse participant barriers to weight loss and physical activity adherence. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:16. CrossRef | PubMed

- 24. O’Hara BJ, Gale J, McGill B, Bauman A, Hebden L, Allman-Farinelli M, et al. Weight-related goal setting in a telephone-based preventive health-coaching program demonstration of effectiveness. Am J Health Promot. 2017;31(6):491–501. CrossRef | PubMed

- 25. Sheldon KM, Elliot AJ. Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: the self-concordance model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76(3):482–97. CrossRef | PubMed

- 26. Ives Y. What is 'coaching'? An exploration of conflicting paradigms. Int J Evid Based Coaching Mentoring. 2008;6(2):100–13. Article

- 27. O’Hara BJ, McGill B, Phongsavan P. Preventive health coaching: is there room to be more prescriptive? Int J Health Educ. 2016;54(2):82–94. CrossRef

- 28. Lakerveld J, Ijzelenberg W, van Tulder MW, Hellemans IM, Rauwerda JA, van Rossum AC, et al. Motives for (not) participating in a lifestyle intervention trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:17. CrossRef | PubMed