Abstract

A continued increase in the proportion of adolescents who never smoke, as well as an understanding of factors that influence reductions in smoking

among this susceptible population, is crucial. The World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control provides an appropriate structure

to briefly examine Australian and New South Wales policies and programs that are influencing reductions in smoking among adolescents in Australia.

This paper provides an overview of price and recent tax measures to reduce the demand for tobacco, the evolution of smoke-free environment policies,

changes to tobacco labelling and packaging, public education campaigns, and restrictions to curb tobacco advertising. It also discusses supplyreduction

measures that limit adolescents’ access to tobacco products. Consideration is given to emerging priorities to achieve continued declines in

smoking by Australian adolescents.

Full text

Introduction

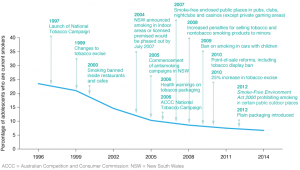

Australia has seen consistent and marked reductions in both adolescent (aged 12−17 years) and young adult (aged 18−24 years) smoking. Between 2001 and 2013, the proportion of young adults reporting they were ‘never smokers’ increased by almost 20 percentage points, from 58% to 77%.1 Adolescent smoking is also at a record low, with only 3.4% of people aged 12–17 years smoking daily.1 In addition, the average age of smoking initiation, or first full cigarette smoked, has increased from 14.2 years in 1995 to 15.9 years in 2013.1 In New South Wales (NSW), the latest data show the proportion of adolescents reporting current smoking as 6.7% in 2014, down from 23.5% in 1996 (see Figure 1).2

Figure 1. Factors affecting declines in youth smoking, 1996–2014 (click to enlarge)

Most smokers begin smoking before the age of 25, and, in high-income countries, most begin smoking as adolescents.3 Although smoking prevalence continues a downward trend in countries such as Australia and the US, adolescent ‘replacement smokers’ continue to be targeted by tobacco industry marketing efforts.4

Continuing to increase the proportion of young people (adolescents and young adults) who are ‘never smokers’ is important for improving the overall health of the population. Further, understanding the factors that influence reductions in smoking among this susceptible population is crucial for future policy development.

Substantial progress has been made in tobacco control to further this understanding. The World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) gives its signatories the impetus and structured approach to implement evidence based measures to address tobacco-related harm in their countries. The WHO FCTC provides an appropriate structure to briefly examine policies and programs that are influencing reductions in smoking among Australian adolescents.

Price and tax measures to reduce demand for tobacco

Price measures are considered a critical component of comprehensive approaches to tackling tobacco use in adults and adolescents. The impact of increasing the price of cigarettes on product demand, specifically among adolescents, has been well established for more than three decades.5 The US Surgeon General recently concluded that taxes that increase the cost of tobacco reduce the uptake of smoking and the amount smoked.4 Adolescents from lower socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds are more price-sensitive to such increases than those from higher SES backgrounds.6

In Australia, increased cigarette prices have been strongly associated with reductions in smoking across the general population, lower SES quintiles and adolescents.7,8 Between 1990 and 2005, the average price of a cigarette rose from $0.18 to $0.41.8 Of note, the Australian Government introduced changes to the tobacco excise system in 1999, moving from a weight-based system (which was enabling the proliferation of larger and cheaper lightweight cigarette packs) to a ‘per-stick’ system. During this time, national adolescent smoking prevalence (smoking in the past month) declined from 22.9% to 13.3%.8 After adjusting for other tobacco control policies that were active in Australia during this time, increasing cigarette prices was associated with reductions in adolescent smoking.8 In 2010, tobacco excise increased by 25%, with four subsequent annual increases of 12.5% from 2013 to 2016.

Nonprice measures to reduce the demand for tobacco

Appropriately funded, sustained smoke-free environment policies targeted at the adult population (in particular, stronger clean indoor air restrictions) and adult-targeted mass media campaigns (as part of overall per capita national tobacco control funding) have been found to reduce smoking by adolescents.8-10 Australian regulatory changes that increased the size of graphic health warnings and introduced plain packaging are reducing cigarette pack appeal among adolescents11, and recent regulatory changes further restricting tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship at the point of sale have also helped to reduce smoking among Australian adolescents.12,13

Increasingly restrictive smoke-free environment regulations in indoor and certain outdoor public places have been introduced over the past 6 years in Australia. These include bans on smoking near children’s playgrounds, in open areas of public swimming pools, at major sports grounds, within specified distances of public buildings, at public transport stops and stations (including railway stations, bus stops, light rail stops, ferry wharves and taxi ranks), and in outdoor dining areas of restaurants, cafes and licensed premises. In NSW, the Public Health (Tobacco) Act 2008 made it an offence (from July 2009) to smoke in a car with a child under the age of 16, and imposes a $250 on-the-spot fine for the driver and any passenger breaking this law. Under the Smoke-free Environment Act 2000, smoking has been banned in NSW commercial outdoor dining areas since July 2015.

Australia has also seen significant increases in national- and state-funded mass media campaigns. The National Tobacco Campaign was launched in June 1997, and states and territories increased their investment in public health warnings about tobacco in subsequent years. In 2005, NSW and Victoria spearheaded a graphic health warning campaign, which was a major collaborative effort between states and territories.14 In 2006, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission launched a tobacco company–funded campaign to inform smokers that low-yield cigarettes were not a healthier alternative.15 Under the NSW Tobacco Strategy 2012–2017, NSW continues to invest in mass media campaigns as part of a comprehensive approach to tackling tobacco consumption.

Australia has been at the forefront of developments aimed at reducing the appeal of cigarette pack branding, through innovative packaging and labelling strategies. The introduction of graphic health warnings in 2006 was associated with reduced intentions to smoke among adolescents.16 A key objective of the Australian Government’s tobacco plain packaging measure, introduced in 2012, was to reduce the attractiveness and appeal of tobacco products to consumers, particularly adolescents. Although it is too early to assess the long-term impact of tobacco plain packaging, early results suggest that it has already reduced cigarette pack brand association among Australian adolescents, thus reducing the appeal of cigarette packs.11

The Tobacco Advertising Prohibition Act 1992 banned the broadcast and publication of tobacco advertisements in Australia. State and territory legislation, such as the NSW Public Health (Tobacco) Act 2008, banned in-store and other forms of advertisement and promotion of tobacco brands and products, and sponsorship of public events. Bans on tobacco retail point-of-sale displays have been shown to positively impact smoking-related outcomes for adolescents and further denormalise smoking.12 However, with traditional forms of tobacco advertising closed off, tobacco companies are seeking alternative ways to promote their products. On average, for every additional hour that young people spend on the internet daily, exposure to smoking in video games increases by 8%.17

Core provisions to reduce supply

The positive effect of government regulations aimed at controlling the supply of tobacco products to children and adolescents is well established.12,18 Preventing sales to minors can help to prevent the uptake of smoking, thus contributing to reduced smoking rates among minors.18,19 Compliance is achieved through education, monitoring and enforcement of the law.18,19

In Australia, enforced tobacco control legislation has also contributed to declines in smoking by adolescents by restricting the supply of tobacco to minors and supporting denormalisation of smoking.8 In NSW, the Public Health (Tobacco) Act 2008 makes it illegal to sell tobacco products and nontobacco smoking products (e.g. herbal cigarettes) to minors in NSW, and prohibits the sale of cigarettes ‘per stick’ or in packs containing fewer than 20 cigarettes. The Act also includes a range of point-of-sale provisions that cover restrictions on tobacco advertising, promotion, packaging and point-of-sale display. Cigarette vending machines are only allowed in licensed venues restricted to those older than 18 years, and purchases can only be made when activated by venue staff or when a token is purchased from venue staff.

Sales to minors and point-of-sale provisions are enforced by NSW Health inspectors, who conduct random and complaints-based inspections of tobacco retailers to monitor compliance with the law. Noncompliant retailers face substantial fines. For example, the Act imposes penalties of up to $11 000 for individuals selling a tobacco product to a minor, and $55 000 for corporations, with higher penalties for repeated breaches. Similar laws exist in other Australian states and territories.

Emerging priorities

This paper provides an update on the status of smoking by adolescents in Australia and NSW, particularly on the policies and programs aligned with the WHO FCTC that are influencing reductions in smoking. Significant progress has been made, but further action is required to achieve continued declines in smoking by Australian adolescents by preventing uptake and aiding quitting. Constant vigilance is needed to address new and innovative tobacco marketing strategies. Proven effective strategies will require continued investment, as outlined in the WHO FCTC. This includes further increases in tobacco excise, and the delivery of tailored and integrated marketing communication strategies for anti-tobacco campaigns that motivate and support quitting across all media platforms. Lastly, the ongoing monitoring and enforcement of tobacco legislation by states and territories will continue to be critical.

Copyright:

© 2016 Dessaix et al. This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National drug strategy household survey: detailed report 2013. Canberra: AIHW; 2014 [cited 2015 Nov 18]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129549469

- 2. Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence. New South Wales school students health behaviours survey (SAPHaRI): 2014 report in press. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2015.

- 3. The World Bank. Curbing the epidemic: governments and the economics of tobacco control. Tob Control. 1999;8(2):196−201. CrossRef | PubMed

- 4. Surgeon General. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General, 2012. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2012 [cited 2015 Nov 18]. Available from: www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/preventing-youth-tobacco-use

- 5. Lewit EM, Coate D, Grossman M. The effects of government regulation on teenage smoking. J Law Econ. 1981;24(3):545−69. CrossRef

- 6. Brown T, Platt S, Amos A. Equity impact of interventions and policies to reduce smoking in youth: systematic review. Tob control. 2014;23(e2):e98−e105. CrossRef | PubMed

- 7. Siahpush M, Wakefield MA, Spittal MJ, Durkin SJ, Scollo MM. Taxation reduces social disparities in adult smoking prevalence. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4):285−91. CrossRef | PubMed

- 8. White VM, Warne CD, Spittal MJ, Durkin S, Purcell K, Wakefield MA. What impact have tobacco control policies, cigarette price and tobacco control programme funding had on Australian adolescents' smoking? Findings over a 15-year period. Addiction. 2011;106(8):1493−502. CrossRef | PubMed

- 9. White VM, Durkin SJ, Coomber K, Wakefield MA. What is the role of tobacco control advertising intensity and duration in reducing adolescent smoking prevalence? Findings from 16 years of tobacco control mass media advertising in Australia. Tob Control. 2015;24(2):198−204. CrossRef | PubMed

- 10. Wakefield MA, Coomber K, Durkin SJ, Scollo M, Bayly M, Spittal MJ, et al. Time series analysis of the impact of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence among Australian adults, 2001−2011. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:413−22. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. White V, Williams T, Wakefield M. Has the introduction of plain packaging with larger graphic health warnings changed adolescents’ perceptions of cigarette packs and brands? Tob Control. 2015;24 Suppl 1:ii42−ii9. CrossRef

- 12. Dunlop S, Kite J, Grunseit AC, Rissel C, Perez DA, Dessaix A, et al. Out of sight and out of mind? Evaluating the impact of point-of-sale tobacco display bans on smoking-related beliefs and behaviors in a sample of Australian adolescents and young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):761−8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 13. Lovato C, Watts A, Stead LF. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(10):CD003439. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. Cancer Institute NSW. Health warnings; 2014 Feb 10 [cited 2015 Apr 17]; [about 1 screen]. Available from: www.cancerinstitute.org.au/prevention-and-early-detection/public-education-campaigns/tobacco-control/health-warnings

- 15. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. Low yield cigarettes 'not a healthier option': $9 million campaign; 2005 Dec 19; [cited 2015 Nov 18]; [about 2 screens]. Available from: www.accc.gov.au/media-release/low-yield-cigarettes-not-a-healthier-option-9-million-campaign

- 16. White V, Webster B, Wakefield M. Do graphic health warning labels have an impact on adolescents’ smoking-related beliefs and behaviours? Addiction. 2008;103(9):1562−71. CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. Perez DA, Grunseit AC, Rissel C, Kite J, Cotter, Dunlop S, et al. Tobacco promotion 'below-the-line': exposure among adolescents and young adults in NSW, Australia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:429. CrossRef | PubMed

- 18. DiFranza JR. Which interventions against the sale of tobacco to minors can be expected to reduce smoking? Tob Control. 2012;21(4):436−42. CrossRef | PubMed

- 19. Tutt DC. Enforcing law on tobacco sales to minors: getting the question and action right. N S W Public Health Bull. 2008;19(11−12):208−11. PubMed