Abstract

Objectives and importance of study: Interventions are needed to help general practitioners (GPs) better support clients living with age-related hearing loss. This project canvassed stakeholder views regarding how GPs might better support people with hearing loss.

Study type: A group concept-mapping approach was used to identify enablers to improving the way in which GPs could support people with age-related hearing loss.

Methods: Concept-mapping techniques were used to gather the perspectives of GPs (n = 7), adults with hearing loss (n = 21), and professionals working with GPs (n = 4) in Australia. Participants generated statements in response to the question, “What would enable GPs to better support people with hearing loss?” Participants then grouped and ranked these statements via an online portal.

Results: Five concepts were identified: 1) making hearing assessment part of routine care; 2) asking questions and raising concerns; 3) listening with empathy and respect; 4) having knowledge and understanding; 5) being connected to expert hearing professional networks. Statements contained within all five concepts were deemed to be highly beneficial in this context, with no individual concept identified to be more or less beneficial than any of the other four concepts.

Conclusions: A wide range of hearing-specific and general communication approaches were identified that could potentially help GPs to better support their adult patients with age-related hearing loss.

Full text

Introduction

Hearing loss is one of the most prevalent chronic health conditions worldwide and the third-leading cause of years lived with disability.1 Age-related hearing loss causes communication difficulties, social breakdown and fatigue2, and increases risk for cognitive decline3 and psychological symptomatology.4 Although available interventions are effective for reducing the impacts of age-related hearing loss, help-seeking and intervention uptake remain low. Consequently, millions of adults around the world continue to experience functional, social and emotional impacts due to age-related hearing loss.

Research has shown that non-audiological factors, such as support from others (family, friends and carers), self-reported impairment, and beliefs about the benefits of hearing aids are the most influential factors for an adult seeking help and successfully using hearing devices.5,6 Less is known about how primary health care professionals, such as general practitioners (GPs), can positively influence hearing help-seeking and uptake in their adult patients. GPs are well placed to have early conversations with people who may have – or may be at risk of – hearing loss, and encourage patients to take action.7 Governments endorse the role of GPs in detection and support of hearing loss symptoms. For example, an Australian Parliamentary Committee recommended in 2017 that efforts be made to “encourage people who may be experiencing hearing loss to seek assistance, and encourage general practitioners and other relevant medical practitioners to actively enquire about hearing health of their patients, particularly those aged 50 years and over”.8

Previous research found that GPs’ rates of identifying hearing loss and counselling patients regarding action were relatively low7; GPs referred only half of their patients with hearing loss to specialist hearing services, and took little other action. Moreover, an exploration of Australian medical practitioners’ attitudes to discussing hearing found that while surveyed doctors reported a high awareness of hearing loss in adult patients, they did not fully understand the consequences of hearing loss nor the benefits of hearing technology, and sometimes made assumptions that older adults would not prioritise hearing.9 Similar findings have been echoed in the US, where research has found that most of the surveyed internal medicine and family physicians were unaware of how they might detect hearing loss and were unlikely to raise the topic unless it was broached by the patient.10

Together, these findings suggest that there is a gap between GPs’ knowledge of the evidence regarding age-related hearing loss and the translation of this evidence into practice in the clinic. The purpose of this project was to work towards development of an intervention to enable GPs to better support adult patients on their journey to hearing rehabilitation by exploring the potential role of the GP in managing age-related hearing loss. This study is the second instalment of a project looking at the role of the GP in managing age-related hearing loss. Where the first study described current practices11, this study is a first step towards developing an intervention, and exploring potential enablers that might improve the way in which GPs could provide support to people with age-related hearing loss.

Methods

Concept mapping is a participatory, mixed-methods approach used to integrate the experiences and expertise of multiple stakeholder groups.12 It is a dynamic approach, with the online data collection processes facilitating engagement with participant groups which may usually be difficult to recruit due to time and travel restrictions. Furthermore, participants play an active role in not just generating the data, but also synthesising and interpreting the data, thus providing a basis for further discussion, interpretation and action.12 Involving consumer and community representatives in research design recognises their right to be involved in health and medical research that concerns them.

Participants

As described previously11, three stakeholder groups were recruited for this study: 1) adults with hearing loss; 2) GPs currently working in Australia; and 3) professionals who work with GPs in Australia, including GP clinic practice managers, practice nurses and university medical school lecturers.

| Demographics | Adults with hearing loss (n = 21) |

GPs (n = 7) |

Professionals working with GPs (n = 4) |

| Participant age range (years) (median, SD) |

57–86 (69, 8) |

28–60 (40, 11) |

29–40 (32, 6) |

| Gender | |||

| Female n (%) | 14 (67) | 5 (71) | 4 (100) |

| Male n (%) | 7 (33) | 2 (29) | 0 |

| Geographical location | |||

| Queensland | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Victoria | 7 | 7 | 2 |

| Western Australia | 9 | 0 | 2 |

GP = general practitioner; SD = Standard deviation

Data collection procedure

Participants contributed to up to three data collection sessions using the online portal Concept Systems (Ithaca, NY: Concept Systems Incorporated; 2011): 1) brainstorming; 2) grouping; and 3) rating, as summarised below (see Supplementary Table 1 for further detail, available from: doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17036489.v1).

Brainstorming

Participants were asked to provide statements in response to the question: “What would enable GPs to provide better support to people with hearing loss? Examples might include certain skills or access to particular tools.” They were provided with the focus prompt: “In my opinion, a way that GPs could better provide support to people with hearing loss is…” Participants were encouraged to brainstorm as many responses as possible to the question, entering them into the online system. De-identified statements contributed by other participants were available for all participants to see, grouped according to stakeholder category. Participants could enter new statements that built on existing statements or enter completely new ideas. Participants were only able to add new statements to the list, not to change or comment directly on each other’s statements. The brainstorming activity was available in the online portal for 6 weeks.

Following the brainstorming task, the research team reviewed all the statements to eliminate irrelevant statements (that did not answer the question) and edited the remainder to ensure they were clear and understandable. This final list of statements was then used for the subsequent grouping and rating activities.

Approximately 2 weeks after completion of the brainstorming activity, participants were asked to log into the portal again, to complete the grouping and rating activities.

Grouping

Participants were presented with the list of brainstormed statements and asked to group them in a way that made sense to them. They received the following instructions: 1) there is no right or wrong way to group the statements; 2) there should not be a “Miscellaneous” or “Other” group; and 3) a statement could be put in its own group if it is unrelated to the other statements or if it stands alone as a unique statement. Participants were required to provide a short title that captured the content of each group they created.

Rating

Participants were given the list of brainstormed statements and asked to rate them on a 5-point Likert scale as to:

1) “How beneficial for the patient would each of these approaches be to the provision of successful hearing loss management?” (1 = little benefit to the patient to 5 = enormous benefit to the patient); and

2) “How beneficial for the GP would each of these approaches be to the provision of successful hearing loss management?” (1 = little benefit to the GP to 5 = enormous benefit to the GP).

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Concept Systems software (Ithaca, NY: Concept Systems Incorporated; 2011) and IBM SPSS Statistics software for Windows (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; version 24). Multidimensional scaling was used to generate a point map, a graphic representation of the results of the grouping task, wherein each statement is represented by an individual point, with the proximity of the points indicating the relationship of statements to one another. A stress index value was computed to test strength of the multidimensional scaling analysis, with a value below 0.365 indicating an acceptable fit.13 Hierarchical cluster analysis was used to determine the overarching concepts indicated by the participants’ grouping data. This was graphically displayed via a cluster map depicting clusters of points (statements) determined by a consensus of how the participants grouped the individual statements. Four members of the research team (RJB, CB, SF and NC) selected the appropriate number of clusters after reviewing the statements within each cluster and discussing which cluster configuration best fit the data; that is, it made sense given the way that statements were grouped within the cluster configuration14 (for further information see Supplementary Table 1, available from: doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17036489.v1). Each cluster, comprising a distinct concept, was given a name that embodied the concept contained therein. Concept names were informed by the names suggested by the participants during the grouping activity. A split-half reliability measure was conducted to evaluate the validity of the final concept map using the Spearman-Brown Prophecy Formula.

Reliability estimates of the rating data were calculated using Cronbach’s alpha to determine internal consistency.15 Welch’s t-test was used to compare the mean ratings between clusters. A Go-zone graph, a bivariate scatter plot based on the participants’ rating data, was generated displaying the individual statements on an X/Y graph divided into quadrants. Participants’ mean ratings for “Benefit to the GP” were plotted against “Benefit to the patient” to identify those individual statements (approaches to managing hearing loss) that were most beneficial to both parties.

Ethics

This project was approved by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number: 1851579.2).

Results

The brainstorming activity was completed by 32 participants: 21 adults with hearing loss; 7 GPs; and 4 professionals working with GPs (Table 1). Although we attempted to recruit GPs from across Australia, participating GPs were all practising in urban cities in Victoria. Nineteen participants completed the grouping activity (59.38% retention rate). Of these, 11 were adults with hearing loss, 6 GPs, and 2 professionals working with GPs. The rating activity was completed by 16 participants (50% retention rate): 9 adults with hearing loss; 4 GPs; and 3 professionals working with GPs. The lower response rate was likely due to the grouping and rating activities being more complex and time consuming than the brainstorming activity to complete. Sample sizes achieved at each stage of the study met recommendations for concept mapping research.12,15

Editing the raw brainstormed statements resulted in a final list of 76 statements (See Supplementary Table 2, available from: doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17036687.v1). Participants grouped these statements into anywhere from 4 to 24 groups (mean 9.84, standard deviation [SD] 6.44). The final cluster map selected had a stress index of 0.2524, suggesting that the concept map appropriately represented the grouping data.15 Reliability testing of the grouping task using split-half correlation and Spearman–Brown correction was 0.904, suggesting high consistency in the way that the individuals grouped the data.12

Five key concepts were identified in the data:

1) Making hearing assessment part of routine care: Conducting hearing screenings, making diagnoses, and discussing hearing loss management. This concept also described the importance of taking thorough case histories that identify communication difficulties, and of being aware of high-risk groups.

2) Asking questions and raising concerns: Making the time to talk about hearing loss and discussing the benefits of intervention. Statements within this concept described the role of the GP in starting the conversation about hearing loss and making the patient aware of possible hearing loss if the doctor suspects it. This concept also described the importance of improving GPs’ skills relating to communicating with the hard of hearing, such as facing the patient when giving important medical information.

3) Listening with empathy and respect: Showing respect and compassion when listening to and communicating with patients about hearing, hearing loss and hearing management.

4) Having knowledge and understanding: Having an in-depth knowledge and understanding of hearing loss to assist shared decision making, information dissemination, and hearing loss self-management. This concept also described the doctor’s ability to share information, have up-to-date knowledge on management options (including hearing aids), and support people to take action regarding their hearing loss.

5) Being connected to expert hearing professional networks: Having relationships with local, reputable hearing care providers and non-GP specialists.

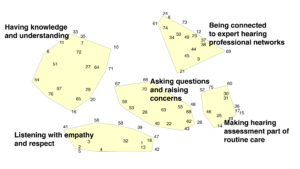

The concept map (Figure 1) depicts these key concepts in the two-dimensional space. The central location of the concept “asking questions and raising concerns” suggests that participants deemed it to be separate but closely related to all of the other concepts. Reliability estimates of the rating data demonstrated high internal consistency for all five concepts across both rating scales (Table 2). The mean rating scores for each of the five concepts were all situated at the high end of the rating scale (Table 3). There was no significant difference between the mean rating scores across the five concepts, or between rating scales; that is, none of the five concepts was deemed to be more or less beneficial than any of the other concepts.

Figure 1. Concept map depicting five key concepts that would enable physicians to provide better support to people with hearing loss (click to enlarge)

Note: Each number represents a brainstormed statement (See Supplementary Table 2, available from: doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17036687.v1). Statements that appear in closer proximity to each other were more often grouped together by participants during the grouping activity.

Table 2. Reliability estimates of the rating data for each of the five concepts, across both rating scales (Cronbach’s alpha)

| Concepts | Benefit to the patient (α) | Benefit to the GP (α) |

| Making hearing assessment part of routine care | 0.935 | 0.914 |

| Asking questions and raising concerns | 0.959 | 0.974 |

| Listening with empathy and respect | 0.931 | 0.955 |

| Having knowledge and understanding | 0.948 | 0.954 |

| Being connected to expert hearing professional networks | 0.948 | 0.949 |

Table 3. Mean concept rating scores for each of the rating questionsa (cohorts combined)

| Concepts | Benefit to the patient (mean) | Benefit to the GP (mean) |

| Making hearing assessment part of routine care | 4.28 | 4.08 |

| Asking questions and raising concerns | 4.20 | 4.05 |

| Listening with empathy and respect | 4.31 | 4.05 |

| Having knowledge and understanding | 4.25 | 4.08 |

| Being connected to expert hearing professional networks | 4.18 | 4.09 |

a Participants rated statements on a 5-point Likert scale in response to the question: “How beneficial for the patient/GP would each of these approaches be to the provision of successful hearing loss management?” (1 = little benefit to 5 = enormous benefit).

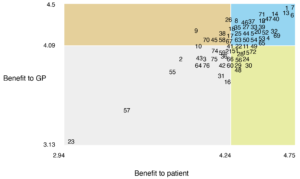

The Go-zone graph provides a visual representation of participants’ mean ratings for individual statements, with ‘benefit to GP’ plotted against ‘benefit to patient’ (Figure 2). This facilitates identification of the approaches to managing hearing loss that were considered most beneficial to both parties. Almost half of the approaches identified by participants (34/76) fell within the top right quadrant, deemed to be highly beneficial to both doctors and patients. They were fairly evenly distributed across the five concepts: 1) Making hearing assessment part of routine care (5/34); 2) Asking questions and raising concerns (5/34); 3) Listening with empathy and respect (7/34); 4) Having knowledge and understanding (9/34); and 5) Being connected to expert hearing professional networks (8/34). The four individual statements deemed to be the most beneficial to both doctors and patients were: ‘listening to people’s concerns’; ‘being better educated regarding management options for age-related hearing loss’; ‘being aware of schemes available to assist patients in accessing hearing aids’; and ‘listening to patient’s concerns’.

Figure 2. The Go-zone graph provides a visual representation of participants’ mean ratings for select individual statements (click to enlarge)

Note: Each number inside the graph represents a brainstormed statement (See Supplementary Table 2, available from: doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17036687.v1).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate what is needed to enable GPs to better provide support to adults with hearing loss. Of the five key concepts identified by participants, three were specific to hearing (knowledge, professional networks and routine practices) and two described traits required for high-quality patient care more broadly, not just to improve hearing loss support (asking questions and listening with empathy and respect). Through the rating activities, participants indicated that all of these concepts were equally beneficial, and beneficial for both patients and doctors.

Having knowledge and understanding: Research suggests that GPs have a high level of awareness about their older patients’ susceptibility to hearing loss but appear less certain about their role in facilitating early intervention.9,16 Perhaps there is a role for professional bodies to play in improving GPs’ access to education and training regarding hearing loss to assist shared decision making, information dissemination, and self-management of age-related hearing loss.

Making hearing assessment part of routine care: Hearing screening programs are effective for improving symptom identification and help-seeking behaviours (hearing aid uptake).17 There are a range of quick and effective tools available to GPs to help with detection and diagnosis of hearing loss, with studies suggesting involvement of practice nurses to assist with assessment and triage.18

Being connected to expert hearing professional networks: Patients are more likely to self-manage their hearing loss, accept hearing intervention, and experience reduced hearing handicap when their GP actively provides management and referral for their hearing loss.17,18 However, on-referrals for hearing loss in general practice remain low.7 GPs are often uncertain about where to refer their patients19 and whether audiologists are suitably qualified.16 A GP may also underestimate how older patients prioritise their hearing health.9 GPs may benefit from access to an up-to-date hearing health management decision aid and referral guide.

Asking questions and raising concerns: This concept included approaches founded in person-centred care. Its central location on the concept map indicates that participants often grouped these statements with statements from all of the other concepts, suggesting it is interwoven within the other concepts. The broad benefits of person-centred care are well described within general practice research20, and likely extend to hearing support and management.21 Adults with hearing loss have described GPs as being apathetic about helping them manage their hearing concerns.11 For example, up to 85% of older patients report having received no spontaneous advice from their primary care providers regarding hearing22, and health records suggest that even patient-directed enquiries are sometimes dismissed by GPs.7 It is true that there are many competing demands on GPs’ time, and as a result they are required to prioritise urgent or potentially serious health conditions. However, given the mounting evidence of significant social, cognitive and mental health impacts of untreated hearing loss4, supporting patients to identify and manage their age-related hearing loss will likely help improve care across a range of health conditions.

Listening with respect and empathy: Participants highlighted the importance of communication style through this concept. Empathic communication has been shown to be beneficial to patient outcomes such as improved pain control23, reduced treatment anxiety24, and better self-management of chronic health conditions (e.g. diabetes25). Conversely, ineffective communication results in patients’ confusion26 and has been associated with adverse effects on patient compliance with treatment.27 Empathic and respectful communication is of utmost importance when engaging with patients regarding hearing loss. Adults with hearing loss often feel stigmatised by members of the public, family or friends, and even health professionals, as people often respond dismissively to concerns raised.1,28 Hearing loss is often regarded as an unfortunate but benign consequence of ageing, yet the perception of ‘age-appropriate hearing loss’ disregards the distressing functional, social and emotional impacts that unmanaged hearing loss can have on an individual. Paying attention to the language used by patients when they describe their experience of hearing loss could help health professionals better understand the gravity of their patients’ experiences.

Limitations and future directions

The effects of sampling bias must be considered: 1) participants self-selected for the study; 2) participants were all recruited from Australia; and 3) although we attempted to recruit a diverse sample of GPs, participating GPs were all practising in urban cities in Victoria. Participants recruited via other sources or from other parts of the world may have produced different data. Although a near 30% attrition rate was observed across the three rounds of data collection, sample sizes for each activity met recommendations for concept-mapping studies.

Further research is needed to understand the potential enablers to improving the way in which GPs could provide support to people with age-related hearing loss in other jurisdictions. Interventional studies are needed to equip and empower GPs with the skills and resources to better support the detection and management of age-related hearing loss within the primary care setting. Such studies could focus on hearing-specific interventions (e.g. increasing knowledge of hearing loss impacts and management options, increasing professional networks, and incorporating hearing screening and referral into routine practices) or might target traits more broadly required for high-quality patient care (e.g. improving GPs’ attentiveness and listening skills, and ability to discuss patient concerns with empathy and respect).

Conclusions

This study highlights the many ways in which GPs could be better equipped to support patients with age-related hearing loss in their help-seeking and rehabilitation journey. Approaches were described within five overarching concepts: three were specific to hearing (having knowledge and understanding; being connected to expert hearing professional networks; and making hearing assessment part of routine care) and two described more general traits of high-quality patient care more broadly (asking questions and raising concerns; and listening with empathy and respect). There is scope to optimise how GPs support the help-seeking pathway for adults with hearing loss within general practice.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital and Deafness Foundation through the Peter Howson Clinical Research Fellowship program.

We would like to thank the participants for devoting their time, and the hearing clinics and community groups (Lions Hearing Foundation of Western Australia and the Deafness Foundation) for assisting with participant recruitment.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, invited. CB and JV are Guest Editors of this themed issue of Public Health Research & Practice. They had no part in the peer-review process for this paper.

Copyright:

© 2021 Bennett. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K, Hanson SW, Chatterji S, Vos T. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;396(10267):2006–17. CrossRef | PubMed

- 2. Bennett RJ, Saulsman L, Eikelboom RH, Olaithe M. Coping with the social challenges and emotional distress associated with hearing loss: a qualitative investigation using Leventhal’s self-regulation theory. Int J Audiol. 2021:1–12. CrossRef | PubMed

- 3. Lin FR, Ferrucci L, Metter EJ, An Y, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM. Hearing loss and cognition in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neuropsychology. 2011;25(6):763–70. CrossRef | PubMed

- 4. Lawrence BJ, Jayakody DM, Bennett RJ, Eikelboom RH, Gasso N, Friedland PL. Hearing loss and depression in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2020;60(3):e137–54. CrossRef | PubMed

- 5. Meyer C, Hickson L, Lovelock K, Lampert M, Khan A. An investigation of factors that influence help-seeking for hearing impairment in older adults. Int J Audiol. 2014;53(S1):S3–17. CrossRef | PubMed

- 6. Hickson L, Meyer C, Lovelock K, Lampert M, Khan A. Factors associated with success with hearing aids in older adults. Int J Audiol. 2014;53(S1):S18–27. CrossRef | PubMed

- 7. Schneider JM, Gopinath B, McMahon CM, Britt HC, Harrison CM, Usherwood T, et al. Role of general practitioners in managing age-related hearing loss. Med Journal Aust. 2010;192(1):20–3. CrossRef | PubMed

- 8. House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health, Aged Care and Sport. Still waiting to be heard... Report on the Inquiry into the Hearing Health and Wellbeing of Australia. Canberra: Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia; 2017 [cited 2021 Nov 16]. Available from: parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/reportrep/024048/toc_pdf/Stillwaitingtobeheard....pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf

- 9. Gilliver M, Hickson L. Medical practitioners' attitudes to hearing rehabilitation for older adults. Int J Audiol. 2011;50(12):850–6. CrossRef | PubMed

- 10. Robinson BE, Barry PP, Renick N, Bergen MR, Stratos GA. Physician confidence and interest in learning more about common geriatric topics: a needs assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(7):963–7. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Bennett RJ, Fletcher S, Conway N, Barr C. The role of the general practitioner in managing age-related hearing loss: perspectives of general practitioners, patients and practice staff. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):87. CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. Trochim W, Kane M. Concept mapping: an introduction to structured conceptualization in health care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17(3):187–91. CrossRef | PubMed

- 13. Burke JG, O’Campo P, Peak GL, Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, Trochim WM. An introduction to concept mapping as a participatory public health research method. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(10):1392–410. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. Bennett RJ, Laplante-Lévesque A, Meyer CJ, Eikelboom RH. Exploring hearing aid problems: Perspectives of hearing aid owners and clinicians. Ear Hear. 2018;39(1):172–87. CrossRef | PubMed

- 15. Rosas SR, Kane M. Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: a pooled study analysis. Eval Program Plann. 2012;35(2):236–45. CrossRef | PubMed

- 16. Danhauer JL, Celani KE, Johnson CE. Use of a hearing and balance screening survey with local primary care physicians. Am J Audiol. 2008: 17(1):3–13. CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. Hands S. Hearing loss in over-65s: is routine questionnaire screening worthwhile? The J Laryngol Otol. 2000;114(9):661–6. CrossRef | PubMed

- 18. Bennett RJ, Conway N, Fletcher S, Barr C. The role of the general practitioner in managing age related hearing loss: a scoping review. Am J Audiol. 2020;29(2):265–89. CrossRef | PubMed

- 19. Cohen SM, Labadie RF, Haynes DS. Primary care approach to hearing loss: the hidden disability. Ear, Nose Throat J. 2005;84(1):26–44. CrossRef | PubMed

- 20. Brickley B, Sladdin I, Williams LT, Morgan M, Ross A, Trigger K, Ball L. A new model of patient-centred care for general practitioners: results of an integrative review. Fam Pract. 2020;37(2):154–72. CrossRef | PubMed

- 21. Grenness C, Hickson L, Laplante Lévesque A, Davidson B. Patient-centred audiological rehabilitation: Perspectives of older adults who own hearing aids. Int J Audiol. 2014;53(Suppl 1):s68–75. CrossRef | PubMed

- 22. Wallhagen MI, Pettengill E. Hearing impairment: significant but underassessed in primary care settings. J Gerontoll Nurs. 2008;34(2):36–42. CrossRef | PubMed

- 23. Howick J, Moscrop A, Mebius A, Fanshawe TR, Lewith G, Bishop FL et al. Effects of empathic and positive communication in healthcare consultations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J R Soc Med. 2018;111(7):240–52. CrossRef | PubMed

- 24. Soltner C, Giquello J, Monrigal-Martin C, Beydon L. Continuous care and empathic anaesthesiologist attitude in the preoperative period: impact on patient anxiety and satisfaction. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106(5):680–6. CrossRef | PubMed

- 25. Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians' empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):359–64. CrossRef | PubMed

- 26. Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Prognostic disclosure to patients with cancer near the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(12):1096–105. CrossRef | PubMed

- 27. Zolnierek KBH, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826–34. CrossRef | PubMed

- 28. David D, Werner P. Stigma regarding hearing loss and hearing aids: A scoping review. Stigma and Health. 2016;1(2):59–71. CrossRef