Abstract

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Standard Indigenous Question (SIQ) uses a question about ‘origin’ to collect data on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. A 2014 review found strong support among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stakeholders for a question focusing on cultural identity, rather than origin. However the ABS retained the origin question to preserve data continuity. In contrast, an Australian influenza-like illness surveillance system, FluTracking, has included the question: “Do you identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander?” for the past 8 years. Brief consultations found that Aboriginal health professionals and academics preferred the ‘identify’ question as a more accurate descriptor of social realities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities. Statistical collections could adapt to improve the quality of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander data, and seek to reflect reality, not define it.

Full text

Background

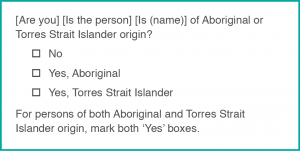

To collect data on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (hereafter, respectfully referred to as Aboriginal), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) uses a Standard Indigenous Question (SIQ) that asks1:

This SIQ is also used by the Australian National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, the New South Wales (NSW) Ministry of Health notifiable disease data collections and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners2 for their data collections.

However, since 2012, FluTracking, a national online influenza-like illness surveillance system3, has asked participants a different question: “Do you identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander?”. FluTracking has made attempts to value Aboriginal people’s views by using the identify question and seeking to encourage those who have cultural affinity to tick the box – although FluTracking could still be undercounting the number of Aboriginal participants, depending on their willingness to disclose their Aboriginality.

In a 2014 review of the SIQ, the ABS found that the origin question was ‘fit for purpose’ and had strong support from a large number of data users.1 There was significant concern in relation to the time and resources that would be required to adopt an amended ABS SIQ, and a concern that any change to this question would lead to a break in time series data. However, at the time, the origin question was recognised as a materially different question to that of identity. Aboriginal stakeholders preferred a question that omitted the concept of origin, and focused on cultural identity; “Are you an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person?”. Despite strong support from Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stakeholders for a question that focused on identity, the review outcome was to retain the ‘origin’ question as the Australian standard for the continuity of data over time.1

Self-identification is recognised and accepted as the international standard for establishing Aboriginal identity.4 Government policy and programs should be designed for those who self-identify and have strong cultural affinity. The identification question is an ongoing and contentious issue. It raises many questions and presents some important problems that need addressing, including: who defines Aboriginality? What question do Australian Aboriginal people prefer? What are some of the issues and problems of asking the question? How is Australian Aboriginal data presented; and does this data reflect the true reality of Aboriginal communities?

The ‘identity’ question

The authors conducted a brief internal and external consultation about questions regarding Aboriginal status with approximately 10 Aboriginal health professionals in the Hunter New England Local Health District Health Protection team, as well as a number of Aboriginal academics and public health practitioners in northern NSW and QLD. Consultation took place in 2017. Participants were asked via email if they preferred the FluTracking ‘identify’ question or the ABS SIQ ‘origin’ question. The consultation revealed that the identify question used by FluTracking was preferred by the majority of participants. The identify question addresses current, rather than historical, social and cultural factors that mediate influenza infection and severity of infection. Extended family networks mediate both the transmission of infectious diseases and the need for culturally appropriate disease control responses. Respondents to the brief consultation considered that the identify question had a deeper meaning that reflected an individual’s personal journey, nature of being, and pride in their cultural identity. An individual’s identity is interconnected to the cultural dimensions of spirituality5, language, tradition, and sense of belonging to family, community and country.6,7 Identity goes far beyond just having an ancestral link as the origin questions implies.

Implications for data quality

Many factors and barriers exist that affect the quality of Australian Aboriginal data, including but not limited to: lack of understanding of the data’s application; reluctance to disclose Aboriginal status because of past experiences and mistrust of health services; and concerns about confidentiality and the attitude of staff asking the question.1,8,9 Australian Aboriginal identity is fluid, and changes in social environment over the course of an individual’s lifetime may affect identification. Other terms such as ‘First Nations’, ‘First Peoples’ or ‘nation’, or language groups may be preferred in other contexts outside of health.

The term Aboriginal is a Western construct and has been used to collectively describe, define, categorise, and determine Aboriginal peoples based on race, for purposes that serve government departments and agencies in the development of policies and programs. Prior to colonisation of Australia, there were more than 500 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations with their own distinct cultures, traditions, languages and belief systems. Although categorised into two groups for statistical reasons and convenience, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are in no way the same, and current methods in which statistical data are collected, analysed and interpreted fail to recognise the diverse social, cultural and historical differences that exist in communities.9 There have been no less than 67 legal classifications, descriptions or definitions to determine who is an Aboriginal person in Australia, and it is no surprise that this has been a cause for suspicion among Aboriginal people.4,10 Although over time the definitions of identification changed and varied among different states and territories11,12, Aboriginal people were largely not part of the decision making processes. During the early years of European settlement of Australia, Aboriginal people were classified by place of habitation and by blood-quantum definitions.10 During the civil rights movement and self-determination era, there was a shift towards definitions by race and since then, the shift has been towards defining Aboriginality by descent, self-identification and community recognition.4,11

The three-part Aboriginal identification proposed by the Commonwealth Department of Aboriginal Affairs in the 1980s states that: “An Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander is a person of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent who identifies as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander and is accepted as such by the community in which he [or she] lives”. This working definition is currently used by the Local Aboriginal Land Councils. However, the widely-used ABS SIQ does not capture the third part of this definition, rather the question determines Aboriginality by whether or not an individual identifies as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin.1

The ABS data collection is minimalist compared with those of Canada and New Zealand, which attempt to collect current identification, past ancestral connection and specific tribal information on First Nations peoples. In 2016, the Canadian Census asked directly: “Is this person an Aboriginal person, that is, First Nations (North American Indian), Métis or Inuk (Inuit)?”. In addition, the Canadian Census asks about nation/band membership and asks: “What were the ethnic or cultural origins of this person’s ancestors?”13 In 2018, the New Zealand Census asked residents: “Which ethnic group do you belong to?”, as well as “Are you descended from a Maori (that is, did you have a Maori birth parent, grandparent or great-grandparent, etc)?” A further two questions were also asked about the name(s) and region(s) of the person(s) tribe(s).14

The construction of the identity question and the way that data is framed and analysed is positioned within the dominant perspective and reflects the ideas outlined in Foucault’s work on power, knowledge and discourse. Foucault asserts that power and knowledge are inextricably linked, for power produces various types of knowledge, discourse and ‘regimes of truth’.15 Those who exercise power use ideological control to create discourse that provides false information that is deemed true in order to keep subjugated groups in place, the philosopher suggests.16 Identifying oneself as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person on a survey that is being used to collate information about a person’s existence produces knowledge, and in turn produces the idea of identity as determined by institutions that hold power. Identity can then be controlled, analysed, interpreted, monitored and reinforced by such institutions, which can impact on the development, and implementation of public health research and programs. As a result, identity then becomes a product of institutional power.

Taking this Foucauldian perspective, it can be argued that the construction of a question about identity also constructs identity. This statistical ‘Indigenous’ identity, created by institutional power, becomes an imposter, which becomes the focus of epidemiological analyses and public health interventions. Recognising the diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identity, institutions could change current approaches to include additional classifications that reflect how Aboriginal people want to identify themselves, and apply different procedures for recording Aboriginal identity. Such changes in collecting information about Aboriginal peoples may then be able to provide a more accurate descriptor of the social realities of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population.

The value of good quality data

Despite the positive efforts to ensure Aboriginal people have control over determining and managing priorities in the pursuit of social and economic development, a significant health gap remains. Good quality and reliable data on Aboriginal people are valuable for the development of policies that are designed to improve the health status of Aboriginal people and to assess the effectiveness of public health programs. Aboriginal people should have the right to determine and define their Aboriginal identity to counter the deleterious impacts of colonisation, and should be actively involved in the decision making about statistical collections relating to Aboriginal people. It is important for their voices to be heard and honoured, and they should determine how this is done, ensuring the process is culturally appropriate and acceptable. FluTracking selected the question preferred by Aboriginal people on the basis of these considerations.

The ABS has previously demonstrated that it is possible to strengthen Australian statistics by adjusting data collection on sex and gender diversity.17 In response to changing community norms, this important change allows respondents to take extra steps to report their sex and gender without being limited to selecting from ‘male’ or ‘female’, and rather by using a term that the individual is most comfortable with.

Conclusion

Although it will be challenging, statistical collections can adapt to improve the quality of Aboriginal data. If identity, rather than origin, is the more useful epidemiological or sociological determinant, there should be a transition to this question. The ABS could ensure historical relevance of prior data collections by documenting the relative proportion of response to an ‘origin’ and ‘identity’ question within the same cohort. This would assist adjustment between the two definitions over time. The ABS, as a custodian and curator of national statistical data, is necessarily a conservative institution with a commitment to historical consistency of definitions and data. However, ABS data collections should seek to reflect reality not define it. To ignore the reality of fluid and evolving self-identification is to ignore, and depart from, reality.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, not commissioned.

© 2019 Crooks et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Information paper: review of the Indigenous status standard. Canberra: ABS; 2014 [cited 2019 Jan 31]. Available from: www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/Lookup/4733.0Main+Features32014?OpenDocument

- 2. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australian general practice. Melbourne, VIC: RACGP; 2011 [cited 2019 Jan 31]. Available from: www.racgp.org.au/FSDEDEV/media/documents/Faculties/ATSI/Identification-of-Aboriginal-and-Torres-Strait-Islander-people-in-Australian-general-practice.pdf

- 3. Dalton CB, Carlson SJ, McCallum L, Butler MT, Fesja J, Elvidge E, et. al. FluTracking weekly online community survey of influenza-like illness annual report, 2015. Commun Dis Intell. 40(4):E512–20. PubMed

- 4. Australian Law Reform Commission. Essentially yours: the protection of human genetic information in Australia (ALRC report 96). Sydney: ARLC, Commonwealth of Australia; 2003 [cited 2019 Jan 31]. Available from: www.alrc.gov.au/publication/essentially-yours-the-protection-of-human-genetic-information-in-australia-alrc-report-96/

- 5. Grieves V. Aboriginal spirituality: a baseline for indigenous knowledges development in Australia. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies. 2008;28(2):363–98. Article

- 6. Harris M, Nakata M, Carlson B. The politics of identity: emerging indigeneity. Sydney: UTS ePress; 2013. CrossRef

- 7. Dudgeon P, Wright M, Paradies Y, Garvey D, Walker I. Aboriginal social, cultural and historical contexts. Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Canberra: ACER; 2014. p. 325 [cited 2019 Jan 31]. Available from: www.telethonkids.org.au/globalassets/media/documents/aboriginal-health/working-together-second-edition/wt-part-1-chapt-1-final.pdf

- 8. NSW Aboriginal Affairs. Aboriginal identification: the way forward. An Aboriginal peoples' perspective. Sydney: NSW Aboriginal Affairs, Department of Education; 2015 [cited 2019 Jan 31]. Available from: www.create.nsw.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/Aboriginal-identification-in-NSW-the-way-forward.pdf

- 9. Walter M, Andersen C. Indigenous statistics: a quantitative research methodology. New York. Routledge; 2016.

- 10. McCorquodale J. The legal classification of race in Australia. Aboriginal History. 1986;10:7–24. Article

- 11. Australian Law Reform Commission. Recognition of Aboriginal customary laws (ALRC Report 31). Canberra: ARLC; 1986 [cited 2019 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.alrc.gov.au/publication/recognition-of-aboriginal-customary-laws-alrc-report-31/

- 12. Gardiner-Garden J. Defining aboriginality in Australia. Canberra: Department of the Parliamentary Library; 2003 [cited 2019 Nov 13]. Available from: www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/Publications_Archive/CIB/cib0203/03Cib10

- 13. Statistics Canada. 2016 census of population questions, long form (National Household Survey). Ottowa: Statistics Canada; 2015 [cited 2019 Jan 31]. Available from: www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2016/ref/questionnaires/questions-eng.cfm

- 14. Stats NZ Store House. New Zealand census of population and dwellings individual form. Wellington, NZ: Statistics New Zeland [cited 2019 Nov 8]. Available from: statsnz.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p20045coll2/id/713/rec/3

- 15. Weir L. The concept of truth regime. Canadian Journal of Sociology. 2008;12:33(2). Article

- 15. Brookfield SD. The power of critical theory for adult learning and teaching, New York: Open University Press; 2008. p. 119–48.

- 17. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of population and housing: reflecting Australia – stories from the Census, 2016. Sex and gender diversity in the 2016 census. Canberra: ABS; 2018 [cited 2019 Apr 3]. Available from: www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features~Sex%20and%20Gender%20Diversity%20in%20the%202016%20Census~100