Abstract

Objectives: To investigate community support for government-led policy initiatives to positively influence the food environment, and to identify whether there is a relationship between support for food policy initiatives and awareness of the link between obesity-related lifestyle risk factors and cancer.

Methods: An online survey of knowledge of cancer risk factors and attitudes to policy initiatives that influence the food environment was completed by 2474 adults from New South Wales, Australia. The proportion of participants in support of seven food policy initiatives was quantified in relation to awareness of the link between obesity, poor diet, insufficient fruit and vegetable consumption, and physical inactivity with cancer and other health conditions.

Results: Overall, policies that involved taxing unhealthy foods received the least support (41.5%). Support was highest for introducing a colour-coded food labelling system (85.9%), restricting claims being made about the health benefits of foods which are, overall, unhealthy (82.6%), displaying health warning labels on unhealthy foods (78.7%) and banning unhealthy food advertising that targets children (72.6%). Participants who were aware that obesity-related lifestyle factors are related to cancer were significantly more likely to support food policy initiatives than those who were unaware. Only 17.5% of participants were aware that obesity, poor diet, insufficient fruit and vegetable consumption, and physical inactivity are linked to cancer.

Conclusions: There is strong support for all policies related to food labelling and a policy banning unhealthy food advertising to children. Support for food policy initiatives that positively influence the food environment was higher among those who were aware of the link between cancer and obesity-related lifestyle factors than among those who were unaware of this link. Increasing awareness of the link between obesity-related lifestyle factors and cancer could increase community support for food policy initiatives, which, in turn, support the population to maintain a healthy weight.

Full text

Introduction

Recent estimates in Australia show that 3917 cancer cases (3.4% of all cancers) diagnosed in 2010 could be attributed to overweight/obesity, 7089 (6.1%) to inadequate diet and 1814 (1.6%) to inadequate physical activity.1 Body fatness is associated with an increased risk of cancer and other noncommunicable diseases, including type 2 diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease.2,3 The worldwide prevalence of obesity more than doubled between 1980 and 20143, and, in Australia, 63% of the adult population is overweight or obese.4

To address the increase in noncommunicable diseases, the World Health Organization has recommended population-based policies, including influencing the food environment through cost-effective and low-cost population-wide interventions.3 These may include restrictions on marketing of foods and beverages that are high in sugar, salt and fat to children, and fiscal policies to increase the availability and consumption of healthy food and reduce consumption of unhealthy foods.3 The food environment is also a focus of the World Cancer Research Fund’s NOURISHING framework, which outlines food policy initiatives that governments may adopt to promote healthy diets, and reduce obesity and obesity-related cancers.5 In Australia, the 2009 National Preventative Health Strategy included recommendations to investigate the use of taxation and/or incentives to promote consumption of healthier foods; introduce food labelling on the front of packaging, and on menus, to support healthier food choices; and reduce the exposure of children and others to the promotion of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods and beverages.6

Government-endorsed food policies can provide an enabling environment for learning healthy preferences, influencing food choices and stimulating positive changes to the food system.7 However, public support and interest is needed to influence governments and counterbalance any negative reaction to policy implementation.8 Public support for food-related obesity prevention policies is strong for regulation of marketing to children and improved food labelling, but weaker for taxation policies.9

Although measuring community support is useful to demonstrate to government the likely acceptance of policy solutions, it is also beneficial to understand what factors will increase that support. Most people recognise that there are ways they can reduce their risk of cancer, such as not smoking and protecting themselves from the sun, but maintaining a healthy weight and eating a healthy diet are not often recognised as important modifiable risk factors.10,11 There is strong evidence that being overweight or obese increases the risk of 11 cancers.2 Although there is also strong evidence that fruit and vegetables and physical activity decrease the risk of several cancers2, being more physically active and eating more fruit and vegetables are also recognised as strategies to maintain a healthy weight, along with other good dietary habits.12 To develop community support for obesity prevention policies, the appropriate framing of messages needs to be identified and the public made aware of the merits of policy solutions.8

This study aimed to investigate the level of support in the community in New South Wales (NSW), Australia, for government-led food policy initiatives to positively influence the food environment, and to investigate whether there is a relationship between awareness of the link between support for food policy initiatives and obesity-related lifestyle risk factors and cancer.

Methods

Study sample

The study methods have been described elsewhere13 and are summarised here. In February 2013, a sample of 3301 adults from NSW completed a 20-minute online survey, the Community Survey on Cancer Prevention, which measured knowledge and attitudes to cancer prevention. Participants were recruited through an email invitation to 30 179 adults residing in NSW from a market research company’s database, with 5290 email recipients starting the survey (17% participation rate). Of those eligible to participate (n = 4274), 77% completed the survey. Quotas were used for demographic characteristics to ensure that the sample reflected the NSW population for sex, age, education level attained and residence (metropolitan or nonmetropolitan). Participants who were currently undergoing treatment for cancer were excluded because they may have had greater knowledge of cancer risk factors than the general population. Those who were employed in advertising or the sale of alcohol or tobacco were excluded because their answers about policy initiatives to address cancer risk factors may have been biased by their work environment. To reduce the overall length of the survey, participants were randomly allocated to four different streams: nutrition, alcohol, tobacco control and sun protection. Data from the 2474 participants who completed the nutrition stream are presented in this paper.

Attitudes towards food policy initiatives

Participants were asked to indicate on a 5-point scale (along with a ‘don’t know’ option) “how strongly do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements?”. The seven statements began with ‘I support’ and then were phrased as stated in Table 1. These policy initiatives about food advertising, food labelling, and pricing and taxation reflect effective, evidence based obesity prevention initiatives identified worldwide as population-wide government policy options to influence the food environment.5 For each policy initiative, responses were recategorised into a binary variable: those who agreed or strongly agreed, and all other response options (strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, don’t know).

Awareness of the adverse health effects of lifestyle factors

Questions prompted awareness of the link between four lifestyle factors and six health conditions, including cancer. Specifically, participants were asked four questions, randomly presented: “Which of the following do you think can result from [being overweight or obese, not eating enough fruit and vegetables, a poor diet, not doing enough physical activity]” and presented with six health conditions: cancer, heart disease, high cholesterol, liver disease, diabetes and obesity, with options to answer ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘don’t know’. Participants were categorised into three mutually exclusive groups: 1) ‘Cancer aware’ – those who identified ‘cancer’ in response to all four obesity-related lifestyle factors; 2) ‘Health aware’ – those who identified at least one health condition as a contributor for all four risk factors; and 3) ‘Unaware’ – those who answered ‘no’ or ‘don’t know’ to at least one risk factor.

Statistical analyses

For each of the seven food policy initiatives, a chi-square test of independence examined the relationship with sociodemographic characteristics (listed in Table 1). Poisson regression models14 with robust standard errors were then used to derive relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of support for each policy initiative by knowledge of health risks (cancer aware/health aware/unaware). RRs and 95% CIs were also calculated for each policy initiative by knowledge of health risks across all four lifestyle factors. RRs were adjusted for sex, age, education and household income. It has been shown that for binary outcomes, exponentiated linear coefficients estimated from Poisson regression provide valid estimates of adjusted RR, and robust standard errors produce CIs that achieve nominal coverage.15,16

Ethics approval for the survey was granted by the Cancer Council NSW Ethics Committee in December 2012.

Results

The distribution of support for food policy initiatives by sociodemographic characteristics is presented in Table 1. Greatest support was observed for the initiative to introduce a colour-coded food labelling system (85.9% of participants agreed or strongly agreed) and to restrict claims being made about the health benefits of foods which are, overall, unhealthy (82.6%). Support was also strong for displaying health warning labels on unhealthy foods (78.7%) and banning unhealthy food advertising that targets children (72.6%). Policy initiatives involving a tax on unhealthy foods received the least support (41%). There was little variation in support for policy initiatives by sex, other than a higher proportion of women than men supporting a colour-coded food labelling system. Age was significantly associated with five of the seven policy initiatives, with a higher proportion of older participants expressing support for each. Having a university degree was significantly associated with support for policies involving a tax or a price increase, and higher income was associated with support for policies involving a tax, warning and colour-coded labels, and restrictions on health claims.

Table 1. Distribution of participants in the Community Survey on Cancer Prevention (NSW) by sociodemographic characteristics and proportion of support for food policy initiatives

| Characteristic | Category | Total, n (%) | Support banning unhealthy food advertising that targets children, n (%) | Support displaying health warning labels on unhealthy foods, n (%) | Support introducing a colour-coded food labelling system, n (%) | Support regulations to restrict claims being made about the health benefits of foods which are, overall, unhealthy, n (%) |

| Sex | Male | 1214 (49.1) | 869 (71.6) | 938 (77.3) | 1001 (82.5) | 1018 (83.9) |

| Female | 1260 (50.9) | 927 (73.6) | 1009 (80.1) | 1124 (89.2) | 1026 (81.4) | |

| χ2 = 1.2 (p = 0.27) | χ2 = 2.9 (p = 0.09) | χ2 = 23.3 (p < 0.0001) | χ2 = 2.5 (p = 0.11) |

|||

| Age | 18–39 | 893 (36.1) | 583 (65.3) | 653 (73.1) | 782 (86.7) | 689 (77.2) |

| 40–59 | 968 (39.1) | 711 (73.5) | 788 (81.4) | 827 (85.4) | 819 (84.6) | |

| ≥60 | 613 (24.8) | 502 (81.9) | 506 (82.5) | 516 (84.2) | 536 (87.4) | |

| χ2 = 51.0 (p < 0.0001) | χ2 = 26.2 (p < 0.0001) | χ2 = 6.8 (p = 0.03) | χ2 = 10.7 (p < 0.005) | |||

| Education | No university degree | 1700 (68.7) | 1216 (71.5) | 1332 (78.4) | 1453 (85.5) | 1399 (82.3) |

| University degree | 774 (31.3) | 580 (74.9) | 615 (79.5) | 672 (86.8) | 645 (83.3) | |

| χ2 = 3.1 (p = 0.08) | χ2 = 0.4 (p = 0.53) | χ2 = 0.8 (p = 0.37) | χ2 = 0.4 (p = 0.53) |

|||

| Annual household Income | ≤ $55 000 | 874 (47.8) | 645 (73.8) | 674 (77.1) | 727 (83.2) | 707 (80.9) |

| > $55 000 | 1183 (35.3) | 857 (72.4) | 964 (81.5) | 1040 (87.9) | 1017 (86.0) | |

| Missing | 417 (16.9) | 294 (70.5) | 309 (74.1) | 358 (85.9) | 320 (76.7) | |

| χ2 = 1.6 (p = 0.46) | χ2 = 12.1 (p = 0.002) | χ2 = 9.3 (p = 0.01) | χ2 = 21.1 (p < 0.0001) | |||

| Total | 2474 (100.0) | 1796 (72.6) | 1947 (78.7) | 2125 (85.9) | 2044 (82.6) |

| Characteristic | Category | Total, n (%) | Support taxing unhealthy foods to pay for health education programs, n (%) |

Support taxing unhealthy foods to contribute to the cost of treating health problems related to a poor diet, n (%) | Support increasing the price of unhealthy foods to discourage people from consuming them, n (%) |

| Sex | Male | 1214 (49.1) | 507 (41.8) | 508 (41.9) | 494 (40.7) |

| Female | 1260 (50.9) | 519 (41.2) | 517 (41.0) | 517 (41.0) | |

| χ2 = 0.1 (p = 0.77) | χ2 = 0.2 (p = 0.68) | χ2 = 0.03 (p = 0.86) | |||

| Age | 18–39 | 893 (36.1) | 372 (41.7) | 363 (40.6) | 357 (40.0) |

| 40–59 | 968 (39.1) | 384 (39.7) | 381 (39.4) | 370 (38.2) | |

| ≥60 | 613 (24.8) | 270 (44.0) | 281 (45.8) | 284 (46.3) | |

| χ2 = 3.7 (p = 0.15) | χ2 = 31.1 (p = 0.0001) | χ2 = 3.0 (p = 0.23) | |||

| Education | No university degree | 1700 (68.7) | 648 (38.1) | 631 (37.1) | 634 (37.3) |

| University degree | 774 (31.3) | 378 (48.8) | 394 (50.9) | 377 (48.7) | |

| χ2 = 25.2 (p < 0.0001) | χ2 = 41.7 (p < 0.0001) | χ2 = 28.7 (p < 0.0001) | |||

| Annual household Income | ≤ $55 000 | 874 (47.8) | 345 (39.5) | 342 (39.1) | 352 (40.3) |

| > $55 000 | 1183 (35.3) | 521 (44.0) | 528 (44.6) | 494 (41.8) | |

| Missing | 417 (16.9) | 160 (38.4) | 155 (37.2) | 165 (39.6) | |

| χ2 = 6.3 (p = 0.04) | χ2 = 10.0 (p = 0.007) | χ2 = 0.8 (p = 0.67) | |||

| Total | 2474 (100.0) | 1026 (41.5) | 1025 (41.4) | 1011 (40.9) |

Knowledge of obesity-related health risks is presented in Table 2. There was a high level of awareness that the four lifestyle risk factors are linked to at least one health condition; only around 1% of participants were unaware that physical inactivity (1.3%), poor diet (1.2%) and obesity (1.3%) can adversely affect health. A higher proportion of participants (8.7%) were not aware of the adverse outcomes related to insufficient fruit and vegetable consumption. Cancer awareness was lower for physical activity than the other three lifestyle factors, and more than half of participants were unaware that each of the four lifestyle factors could be linked to cancer. When combined, 17.5% of participants correctly identified that cancer was associated with all four risk factors.

Table 2. Knowledge of obesity-related health risks in the Community Survey on Cancer Prevention (NSW)

| Question | Response | n (%) |

| Which of the following do you think can result from not doing enough physical activity? | Cancer | 586 (23.7) |

| Health condition (not cancer)a | 1855 (75.0) | |

| No ill effects/Don’t know | 33 (1.3) | |

| Which of the following do you think can result from a poor diet? | Cancer | 1217 (49.2) |

| Health condition (not cancer)a | 1228 (49.6) | |

| No ill effects/Don’t know | 29 (1.2) | |

| Which of the following do you think can result from not eating enough fruit and vegetables? | Cancer | 1132 (45.8) |

| Health condition (not cancer)a | 1127 (45.6) | |

| No ill effects/Don’t know | 215 (8.7) | |

| Which of the following do you think can result from being overweight/obese? | Cancer | 994 (40.2) |

| Health condition (not cancer)b | 1449 (58.6) | |

| No ill effects/Don’t know | 31 (1.3) | |

| Combined responses | ‘Cancer aware’: identified cancer as a risk for all four factors | 433 (17.5) |

| ‘Health aware’: identified at least one health condition as a risk for all four factors | 1790 (72.4) | |

| ‘Unaware’: answered ‘No’ or ‘Don’t know’ to at least one factor | 251 (10.1) |

a Heart disease, diabetes, high cholesterol, being overweight or obese, and/or liver disease

b Heart disease, diabetes, high cholesterol, and/or liver disease

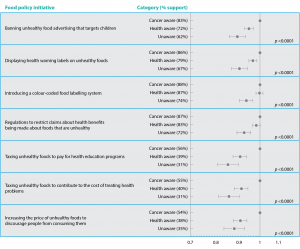

After adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, participants who were ‘Unaware’ (those who did not identify any health conditions as linked to obesity-related risk factors) were significantly less likely to support food policy initiatives than those who were ‘Cancer aware’ (those who identified a link between cancer and the four lifestyle factors) (Figure 1). Those who were ‘Health aware’ (those who identified at least one health condition as a risk for all four obesity-related risk factors) were significantly less likely to support five of the seven food policy initiatives than those who were ‘Cancer aware’. The largest variation in RR was in relation to initiatives involving taxes: those in the ‘Unaware’ category were 15% less likely to support a tax on unhealthy foods to pay for health education programs (RR = 0.85; 95% CI 0.80, 0.89) and 15% less likely to support a tax to contribute to the cost of treating health problems (RR = 0.85; 95% CI 0.81, 0.90).

Figure 1. Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals of being supportive of each food policy initiative for participants who were aware of the link between cancer and lifestyle risk factors (click to enlarge)

Note: Figure shows ‘Cancer aware’ (n = 433) compared with those who were aware of the link to health conditions other than cancer (‘Health aware’; n = 1790) and those who were unaware of the health risks (‘Unaware’; n = 251) in the Community Survey on Cancer Prevention, New South Wales (2013). Relative risks adjusted for age, sex, education and income.

Discussion

This population study in NSW showed strong support for policies related to food labelling and restrictions on advertising to children, and less support for policies involving a tax or a price increase. Participants without knowledge of the link between obesity and related risk factors and cancer were significantly less likely to support all policy initiatives than those who were aware.

Previous studies on attitudes to food policy initiatives are consistent with our results. A 2012 omnibus survey in the UK also found less support for taxation-based policies (32%), and more support for food labelling (66%) and advertising restrictions (57%).17 Similarly, an Australia-wide study in 2010 found higher levels of support for a ‘traffic-light’ style of labelling (87%) and restrictions on advertising unhealthy food to children on television (83%) than taxing unhealthy foods and using the money for health programs (62%).9 That study reported stronger support for increasing the price of unhealthy foods to reduce the cost of healthy foods (71%) than our study, although a direct comparison cannot be made because more contextual information was provided leading up to each question in the 2010 study (e.g. the taxation questions were preceded by the question “would you be in favour or against government taking the following actions to support healthy eating?”).9 The finding that a tax was least supported aligned with other results that show that interventions that are less intrusive, such as those that provide information, are more acceptable than those that aim to discourage behaviours through disincentives such as taxation.18 Similar to findings of a 2013 systematic review, our study also found that, generally, women and older people were more supportive of policy interventions than other groups.18

Support for food policy initiatives in our study was more likely among adults who were aware of the link with cancer. Those who were unaware or unsure of the link between the health conditions and the four risk factors showed the lowest level of support for any food policy initiative. A systematic review of public acceptability of government intervention to change smoking behaviours found that respondents who were aware of the harm of smoking were more likely to support policies to restrict it.18 Results from participants in the alcohol stream of this survey found that awareness that risky alcohol consumption was a cancer risk factor was a significant predictor of support for alcohol management policies.13 Although there is limited research into knowledge of behaviours and food policy interventions, a study in the UK found that those who believed the food environment was a cause of obesity were more likely to support food policy solutions.17

Like our study, a 2005 survey of 3001 Victorian adults showed that, at most, half of respondents associated obesity-related risk factors with cancer: lack of vegetables (51%), lack of fruit (48%), overweight (45%) and lack of exercise (45%).10 There is clearly an opportunity to raise awareness of the preventable risk factors for cancer that are related to overweight and obesity. Recent updates to cancer preventability estimates for Australia found that almost 4000 cancer cases (3.4% of all cancers) diagnosed in 2010 were attributable to overweight/obesity19, so it is timely to translate the evidence into cancer prevention messages. Government-endorsed social marketing campaigns and messaging from cancer organisations are needed to increase awareness of preventable cancer risk factors, particularly those that support maintaining a healthy weight.

The food environment influences what people eat.20 Promotion and pricing of foods are important influencers on consumers’ purchasing decisions, and government policies to change the food environment have been suggested to promote healthy eating and address rising obesity rates.5,21 One of the most widely accepted policy interventions is the restriction of unhealthy food marketing to children.5 Restriction of unhealthy food advertising on television was potentially the most cost-effective and cost-saving intervention of 13 interventions assessed for preventing and managing childhood obesity, according to a report that assessed the cost-effectiveness of obesity.22 Another Australian cost-effectiveness analysis showed that both colour-coded traffic-light nutrition labelling and taxes on unhealthy foods were likely to offer excellent value for money as obesity prevention measures.23 Obesity prevention requires bold steps by governments and a multifaceted approach, including policies that have evidence of cost effectiveness.

The results of this study highlight the need to improve communication about the links between obesity and cancer and the lifestyle factors that can contribute to a reduction in cancer risk. With high public acceptance and evidence of effectiveness, restrictions on food marketing to children should remain a priority policy for advocacy attention. Improvements to food labelling, including colour-coded food labelling and strengthening food labelling laws to ensure only healthy foods can carry claims about nutrition content also have high community support. The latter seems an achievable extension of existing food labelling legislation, which would strengthen confidence in food labelling and better support consumers to make healthier food choices.

A limitation of this study is the online sampling. Efforts to include quotas for metropolitan and nonmetropolitan participants, as well as sex, age and education level attained, increased its generalisability. Participants were recruited from a market research panel that self-selected to participate in online surveys. It is possible that people who do not participate in surveys of this type – those who are marginalised, for example – may have poorer knowledge of health risk factors, and therefore the association between knowledge and attitudes observed in our study may be conservative. The low response rate (17%) is above the average participation rate of 13.3% found in a meta-analysis of 199 online surveys.24

Conclusions

Tackling the issue of overweight and obesity requires a multifaceted approach that includes population-wide and environmental solutions, most effectively led by government policy. To advocate for policy intervention, public health agencies need to show governments that the policy options are based on sound scientific evidence and that their constituents support them.25 Improving community awareness of the link between obesity-related lifestyle factors and cancer will maximise the bottom-up efforts to mobilise policy action to improve the food environment.8 This will contribute to a political environment that is more receptive to evidence based policy solutions.

Our finding that people who know about the links between obesity and cancer are more supportive of evidence based policies than those who are not aware of the obesity-related cancer risk factors is useful to inform public information and framing messaging for advocacy efforts. This has good synergy for future social marketing campaigns: increasing awareness of the link between lifestyle factors and cancer increases community support for food policy initiatives that positively influence the food environment, which, in turn, supports the population to maintain a healthy weight. Public health and cancer organisations advocating for obesity prevention policy interventions need to ensure that they are also effectively communicating the increasing evidence of the link between obesity and cancer as a reason for prioritising such interventions.

Copyright:

© 2017 Watson et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Whiteman DC, Webb PM, Green AC, Neale RE, Fritschi L, Bain CJ, et al. Cancers in Australia in 2010 attributable to modifiable factors: summary and conclusions. Aust N Z J Public Health 2015. 39(5):477–84. CrossRef | PubMed

- 2. World Cancer Research Fund International. Cancer prevention & survival, Summary of global evidence on diet, weight, physical activity & what increases or decreases your risk of cancer. London: WCRF; 2015 [cited 2017 Aug 8]. Available from: www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/CUP-Summary-Report.pdf

- 3. World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. Geneva: WHO; 2014 [cited 2017 Aug 8]. Available from: apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/148114/1/9789241564854_eng.pdf?ua=1

- 4. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017. Australian Health Survey: updated results, 2011–2012; 2013 [cited 2017 Aug 8]; [about 1 screen]. Available from: www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/4364.0.55.003Chapter12011–2012

- 5. Hawkes C, Jewell J, Allen K. A food policy package for healthy diets and the prevention of obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases: the NOURISHING framework. Obes Rev. 2013;14 Suppl 2:159–68. CrossRef | PubMed

- 6. Australian Government Preventative Health Taskforce. Australia: the healthiest country by 2020. National Preventative Health Strategy – the roadmap for action. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2009 [cited 2017 Aug 8]. Available from: www.health.gov.au/internet/preventativehealth/publishing.nsf/Content/CCD7323311E358BECA2575FD000859E1/%24File/nphs-roadmap.pdf

- 7. Hawkes C, Smith TG, Jewell J, Wardle J, Hammond RA, Friel S, et al. Smart food policies for obesity prevention. CrossRef | PubMed

- 8. Huang TT, Cawley JH, Ashe M, Costa SA, Frerichs LM, Zwicker L, et al. Mobilisation of public support for policy actions to prevent obesity. Lancet. 2015;285(9985):2422–31. CrossRef | PubMed

- 9. Morley B, Martin J, Niven P, Wakefield M. Public opinion on food-related obesity prevention policy initiatives. Health Promot J Austr. 2012;23(2):86–91. PubMed

- 10. Cameron M, Scully M, Herd N, Jamsen K, Hill D, Wakefield M. The role of overweight and obesity in perceived risk factors for cancer: implications for education. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25(4):506–11. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Morley B, Wakefield M, Dunlop S, Hill D. Impact of a mass media campaign linking abdominal obesity and cancer: a natural exposure evaluation. Health Educ Res. 2009;24(6):1069–79. CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian dietary guidelines. Canberra: NHMRC; 2013 [cited 2017 Aug 8]. Available from: www.eatforhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/the_guidelines/n55_australian_dietary_guidelines.pdf

- 13. Buykx P, Gilligan C, Ward B, Kippen R, Chapman K. Public support for alcohol policies associated with knowledge of cancer risk. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(4):371–9. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–6. CrossRef | PubMed

- 15. Greenland S. Model-based estimation of relative risks and other epidemiologic measures in studies of common outcomes and in case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(4):301–5. CrossRef | PubMed

- 16. Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):199–200. CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. Beeken RJ, Wardle J. Public beliefs about the causes of obesity and attitudes towards policy initiatives in Great Britain. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(12):2132–7. CrossRef | PubMed

- 18. Diepeveen S, Ling T, Suhrcke M, Roland M, Marteau TM. Public acceptability of government intervention to change health-related behaviours: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:756. CrossRef | PubMed

- 19. Kendall BJ, Wilson LF, Olsen CM, Webb PM, Neale RE, Bain CJ, Whiteman DC. Cancers in Australia in 2010 attributable to overweight and obesity. Aust N Z J Pub Health. 2015;39(5):452–7. CrossRef | PubMed

- 20. World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research. Policy and action for cancer prevention. Food, nutrition, and physical activity: a global perspective. Washington: AICR; 2009 [cited 2017 Aug 8]. Available from: www.wcrf-hk.org/sites/default/files/Policy_Report.pdf

- 21. World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013-2020. Geneva: 2013 [cited 2017 Aug 8]. Available from: apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94384/1/9789241506236_eng.pdf

- 22. Magnus A, Haby MM, Carter R, Swinburn B. The cost-effectiveness of removing television advertising of high-fat and/or high-sugar food and beverages to Australian children. Int J Obes. 2009;33(10):1094–102. CrossRef | PubMed

- 23. Sacks G, Veerman J, Moodie M, Swinburn B. Int J Obes. 2011;35(7):1001–9. CrossRef | PubMed

- 24. Hamilton MB. Online survey response rates and times, background and guidance for industry. Longmont, CO: Ipathia Inc./SuperSurvey; 2009.

- 25. Farley TA, Van Wye G. Reversing the obesity epidemic: the importance of policy and policy research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3 Suppl 2):S93–94. CrossRef | PubMed