Abstract

Background: Falls and fall-related injury are emerging issues for older Aboriginal people. Despite this, it is unknown whether older Aboriginal people access available fall prevention programs, or whether these programs are effective or acceptable to this population.

Objective: To investigate the use of available fall prevention services by older Aboriginal people and identify features that are likely to contribute to program acceptability for Aboriginal communities in New South Wales (NSW), Australia.

Methods: A questionnaire was distributed to Aboriginal and mainstream health and community services across NSW to identify the fall prevention and healthy ageing programs currently used by older Aboriginal people. Services with experience in providing fall prevention interventions for Aboriginal communities, and key Aboriginal health services that delivered programs specifically for older Aboriginal people, were followed up and staff members were nominated from within each service to be interviewed. Service providers offered their suggestions as to how a fall prevention program could be designed and delivered to meet the health and social needs of their older Aboriginal clients.

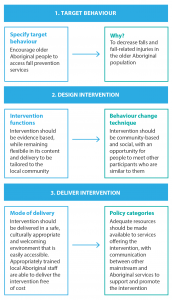

Results: Of the 131 services that completed the questionnaire, four services (3%) had past experience in providing a mainstream fall prevention program to Aboriginal people; however, there were no programs being offered at the time of data collection. From these four services, and from a further five key Aboriginal health services, 10 staff members experienced in working with older Aboriginal people were interviewed. Barriers preventing services from offering appropriate fall prevention programs to their older Aboriginal clients were identified, including limited funding, a lack of available Aboriginal staff, and communication difficulties between health services and sectors. According to the service providers, an effective and acceptable fall prevention intervention would be evidence based, flexible, community-oriented and social, held in a familiar and culturally safe location and delivered free of cost.

Conclusion: This study identified a gap in the availability of acceptable fall prevention programs designed for, and delivered to, older Aboriginal people in NSW. Further consultation with older Aboriginal people is necessary to determine how an appropriate and effective program can be designed and delivered.

Terminology: The authors recognise the two distinctive Indigenous populations of Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Because the vast majority of the NSW Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population is Aboriginal (95.4%)1, this population will be referred to as ‘Aboriginal’ in this manuscript.

Full text

Introduction

Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population is ageing. In 1996, 2.8% of Australia’s total Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population was aged 65 years and older, but this proportion is predicted to more than double to 6.5% by 2026.2 As this older age group grows in size, so too does the burden of age-related health conditions among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Falls significantly affect the health of older people living in Australia, with approximately one-third of people aged 65 years and older experiencing at least one fall each year.3 Fall-related injury is the leading cause of injury-related hospitalisations for Aboriginal people in New South Wales (NSW)4, predominantly affecting women aged 65 years and older, and men aged 60–64 years.5 Fall injury rates increased by an average of 10.2% per year for older Aboriginal people from 2007–08 to 2010–11, compared with a 4.3% average annual increase for older non-Aboriginal Australians.6

Multiple fall prevention programs are now being run in community settings across Australia.7 However, it is uncertain whether older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are accessing these programs, and whether the programs are effective or acceptable for this population.

Previous studies have described difficulties with promoting the uptake of fall prevention services in other populations.8 This has been attributed to the embarrassment associated with falling among older age groups, and a lack of an individual’s awareness of their personal ability to decrease their risk of falling. There are further concerns relating to the acceptability of mainstream health services for older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, with past experiences of discrimination and communication difficulties potentially deterring them from using the services.9

This study aimed to describe fall prevention services being delivered in NSW, and investigate their use by older Aboriginal people. A key goal of this research was to investigate how a fall prevention program could be developed that is culturally acceptable and appealing for older Aboriginal people.

Methods

A questionnaire investigating the use of both healthy ageing services and fall prevention services by older Aboriginal people was distributed using email and fax to Aboriginal and mainstream health and community services operating in NSW. Initial services were identified during a meeting with the Clinical Excellence Commission NSW Falls Co-ordinator Collaborative in April 2014. The project team identified additional services through online healthcare service databases such as Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet, Aboriginal Medical Service directories and NSW Government chronic care contact lists. A total of 628 emails containing a hyperlink to the online questionnaire were sent during a 2-week period, and 27 paper-based questionnaires were faxed to services on request. Services were encouraged to forward the questionnaire to relevant contacts.

Services that indicated any experience in providing fall prevention programs specifically for older Aboriginal people were contacted by telephone by two researchers (CL and JC) to gain additional information on their structure and operation. An interview invitation was extended to staff members who worked predominantly with older Aboriginal clients at each service.

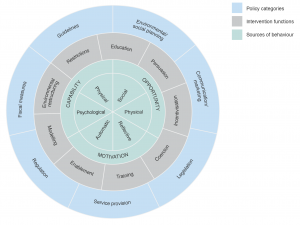

For each service provider who consented to be interviewed, the project team followed up by phone or in person. A structured interview guide was used, based on the framework of the behaviour change wheel (BCW).10 The BCW (Figure 1) investigates how elements of health policy and features of health services influence client interactions with health services, and can be used to inform a “more efficient design of effective interventions”.10

Figure 1. Behaviour change wheel

The interview questions explored the ability of health services to deliver appropriate fall prevention programs to Aboriginal people, and aimed to identify intervention features that would be beneficial and appealing to older Aboriginal people. Both researchers confirmed when new ideas and insights ceased to be provided through the interviews, indicating that data saturation had been achieved. Each interview was audiotaped and transcribed verbatim, with transcripts checked for accuracy and coded in QSR NVivo 10 software.

The responses were analysed thematically, where codes based on the BCW framework were assigned to sections of each interview transcript.11 This paper reports responses in accordance with both STROBE and COREQ reporting guidelines.12,13

All aspects of the study were overseen by an Aboriginal steering committee, ensuring the study was run in a culturally appropriate way and that study goals remained relevant. Ethical approval was granted by the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW Ethics Committee (1010/14).

Results

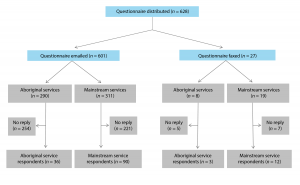

A total of 131 services responded to the questionnaire (overall response rate of 44%; Figure 2). All NSW Local Health Districts were represented, including metropolitan (28% of responses), rural and regional areas (60%) and services available state-wide (12%).

Figure 2. Questionnaire distribution and responses

From all completed questionnaires, 121 of 131 respondents (92%) were unaware of any fall prevention services that were specifically run for Aboriginal people in their area. Only 4 of 131 services (3%) reported that they had provided a mainstream fall prevention program specifically for Aboriginal people. Additionally, 107 of 131 respondents (82%) were not aware of whether Aboriginal people attended mainstream fall prevention programs.

The project team followed up with the four services (two Aboriginal services and two mainstream services) that reported providing fall prevention interventions for Aboriginal communities. Each service had previous experience in offering fall prevention programs to older Aboriginal people, but no programs were being offered at the time of data collection. The past programs had either been run by external parties who no longer had a relationship with the service, or by staff who had since left the service. Little information was available about past program content, delivery or outcomes.

A further five Aboriginal services that delivered healthy ageing programs specifically for older Aboriginal people living in the community were also followed up. Ten service providers were nominated from within the nine services to be interviewed.

The 10 interviewed service providers were from a variety of backgrounds, each experienced in working with older Aboriginal people in a healthcare context. All service providers reported falls as a major health issue for their older Aboriginal clients, and service providers from Aboriginal health services stated that many older clients had never attended a program specifically for fall prevention. The five mainstream fall prevention service providers that were interviewed reported they were unsure of how to promote their programs to local Aboriginal communities, whereas the five service providers working in Aboriginal health were unsure about where to refer older Aboriginal clients to fall prevention interventions being run in the general community.

The interview data were analysed within the BCW framework. Certain themes covered a number of BCW categories, demonstrating the complex relationships between client perspectives, health service functions and the influence of health policy. Direct quotes that best corresponded to these themes were taken from transcripts and used as subheadings to aid in interpreting the data.

The following BCW categories were not acknowledged by service providers:

- Policy categories – legislation

- Intervention functions – coercion, incentivisation, restrictions and modelling

- Sources of behaviour – capability (both physical and psychological)

This potentially indicates that these areas are less relevant for program design and delivery in this context.

Reasons for older Aboriginal people not accessing existing fall prevention programs

“A lot of clients won’t go to mainstream programs”

Two staff members from Aboriginal services and two staff members from mainstream services discussed that their older Aboriginal clientele felt uncomfortable with accessing mainstream programs. Trust in local, well-known, familiar Aboriginal services gave clients confidence to trial new programs there.

Most of our clients come here because they don’t feel safe in the mainstream exercise class. They just don’t feel comfortable. (Aboriginal services coordinator)

“In reality, falls are not a huge consideration for most people”

Three service providers from mainstream services reported that many of their clients did not see the benefit of attending a fall prevention program, because they did not consider falls as a personal health concern. Despite this, all service providers observed falls as having a significant health impact on their older Aboriginal clients.

Clients don’t believe it’s an issue for them, especially with the over 50 group, it’s not an issue, until they have a fall. (Exercise physiologist)

“We need to make our Aboriginal community aware of what’s available”

The majority of service providers reported that their older Aboriginal clients were unaware of existing fall prevention classes being available and were therefore missing out on the opportunity to attend classes. It was suggested that this could be the result of poor health promotion between Aboriginal and mainstream services, or gaps in fall prevention education for health service providers.

Service provider perspectives for developing a successful Aboriginal fall prevention program

“You have to acknowledge the importance of cultural safety”

All Aboriginal service providers said it was necessary to integrate a fall prevention program for older Aboriginal people into existing, well-established and trusted Aboriginal organisations. The combination of a known community venue with familiar staff and previously used transport options were thought to encourage program use, particularly with older people. Additionally, promotion and referral to the program would be possible through other programs at each service.

If [the program] comes here, our clients will come, because they already come here. They’re not going to source [the program] somewhere else. (Service coordinator)

“It’s a social occasion for participants”

The Aboriginal service providers reported that relationships built between participants and program staff during the course of other Aboriginal healthy ageing programs acted as motivation for ongoing attendance.

A client might have been told [to use the program] 10 times but then they just decide to come because their friend is coming. (Exercise physiologist)

Socialising among participants was additionally reported as a good educational tool, with both physical and mental health benefits.

All people can meet in a group and share similar stories and similar experiences. I think it can be a very valuable tool. (Occupational therapist)

“Aboriginal groups need Aboriginal instructors”

The Aboriginal service providers viewed both Aboriginal staff members and Aboriginal instructors as more capable of relating to Aboriginal clients, which contributed to creating a culturally safe environment.

You need to have somebody that knows where [our Aboriginal clients] are coming from because they’re not going to come and see a person that has no clue. (Registered nurse)

Additionally, through employing Aboriginal people from the local community, an immediate familiarity exists between participants and staff. Local staff were thought to remain in their roles for longer periods of time, preventing frequent staff turnover.

[If we use] Aboriginal fitness leaders, people will come to the program because they’re supporting the community and vice versa. (Accredited exercise physiologist)

“We need to meet the criteria”

One staff member from an Aboriginal service and one staff member from a mainstream service stated concern that the programs’ validity and effectiveness in reducing falls risk should not be compromised in the effort to ensure the programs are culturally appropriate.

We want to maintain and completely acknowledge the importance of cultural appropriateness, we also want to ensure best practice – evidence-based best practice isn’t lost in trying to be too entirely culturally appropriate. (Aboriginal health service manager)

Interviewees discussed the need for formally trained staff with the skills to adjust the programs’ content and delivery method to suit participants while maintaining its effectiveness.

“Flexibility is a big thing”

The inflexibility of many previous mainstream health programs had left staff from both mainstream and Aboriginal services unable to adjust or modify the programs to meet the specific needs of their older Aboriginal clients, which differed to those of the general older Australian population, leading to poor participant engagement.

The community [need to] understand it, so that they can relate to it, they can familiarise with it. (Aboriginal care coordinator)

Support required for delivering a successful fall prevention program to older Aboriginal people

“Limited money, limited time, limited resources”

Service providers working in Aboriginal health organisations identified high client numbers, coupled with a lack of funding, staff and resources, as major barriers to providing culturally appropriate Aboriginal fall prevention programs. Funding was seen as necessary to train and employ Aboriginal staff for program delivery, and for ensuring program sustainability.

I guess it’s our vision if we were able to source funding – this is something we would look at – developing our programs. (Aboriginal health service manager)

Cost was reported as a barrier to clients accessing health services. Program fees were identified as particularly troublesome for older people, who often relied on aged care pensions. Costs associated with client transport to and from health services added another barrier, particularly in widely distributed communities.

“Competing priorities”

Despite the availability of many effective and frequently used Aboriginal community health services, staff from Aboriginal services reported that a lack of communication between the services and the lack of emphasis placed on fall prevention was thought to cause clients who are at a high risk of falling to be overlooked for receiving fall prevention assistance.

I guess when people get caught up in that medical model where you’ve got multidisciplinary teams from different angles looking at different things there. Falls is probably not even a huge consideration in reality. (Aboriginal health service manager)

Within Aboriginal services, there was uncertainty as to which service providers were responsible for assessing and referring at-risk patients to fall prevention programs, or delivering appropriate fall prevention advice. There was confusion not only between mainstream and Aboriginal services, but also between providers from different health disciplines.

Themes repeatedly discussed by the service providers during the interviews were included in a program design template, also developed by Susan Michie as an element of her BCW framework (Figure 3).14 A concise program outline was generated using the interview data, highlighting how a fall prevention program could be structured for older Aboriginal people, from the perspective of the service providers.

Figure 3. Program design template

Discussion

Participation in fall prevention programs by older people has been reported to be typically less than 50%15, and can be often as low as 10%.16 A qualitative study by Yardley et al. in 2006 found that older people disengaged from fall prevention programs for a number of reasons. Many participants did not view themselves as being at risk of falling, and others associated falls with embarrassment. Most commonly, participants were not aware of their ability to reduce their own risk of falling.8 The service providers in the current study mentioned most of these reasons when discussing fall prevention and their older Aboriginal clients. The unfamiliarity of mainstream programs for Aboriginal people was an additional deterrent to accessing available programs.

Funding difficulties have been a long-standing obstacle for Aboriginal services in offering long-term health programs, and these are not unique to aged care. Public Aboriginal health funding can originate from a range of federal, state and territory sources.17 As many Aboriginal services offer a variety of programs, funding for one service often comes from numerous grants and funding schemes that can be “overlapping and unclear”.18 Additionally, the majority of these grants are only short to medium term. The ambiguity of funding sources and a lack of funding security put strong restrictions on the type and number of programs that Aboriginal services are able to offer. As mentioned by the Aboriginal service providers, fall prevention is not often viewed as a priority in the Aboriginal aged care setting, and therefore frequently misses out on funding allocation.

Multiple studies have shown low use of mainstream healthcare services by Aboriginal people.19 Fee-charging health services are rarely accessed by Aboriginal people. Of all Aboriginal health expenditure, 72% is attributed to public hospital care, and free-to-use community and health services.19 Currently, nearly all fall prevention programs in NSW charge an attendance fee, ranging from a donation to $22 per session.7

Communication difficulties and a history of discrimination within mainstream health services have left many Aboriginal people (particularly from older generations) hesitant to use Western health services and programs.20 Staff who have not received cultural competency training, coupled with a high staff turnover rate in many public services, creates an unfamiliar environment to older Aboriginal clients, making trust difficult to establish between clients and health workers.21

Employing Aboriginal staff in health services has positive effects on service use by the local Aboriginal community and on patient satisfaction with the service.22 Aboriginal health staff are rare, with only 4891 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working in the health industry nationwide in 2006, comprising 1.0% of Australia’s total health workforce.23 The content and delivery of an exercise-based fall prevention program must meet very specific guidelines to guarantee the program’s effectiveness.24 As a result, allied health professionals or fitness instructors with extensive experience in working with older adults are ideal candidates to run such programs. However, such roles would be difficult to fill from the existing Aboriginal health workforce, where only 54 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander physiotherapists were registered in Australia in 2006, representing 0.4% of the total national physiotherapist workforce.23

Strengths and limitations

The health and community services questionnaire documented fall prevention and healthy ageing programs across the state, focusing on their use by older Aboriginal people. Although we were not able to contact every service in NSW, the use of snowball sampling and referrals from key stakeholders (involved in fall prevention and/or Aboriginal aged care) assisted the project team in identifying and making contact with key organisations. Responses to the questionnaire were received from services located in metropolitan, rural and regional areas, reflecting a broad reach of the questionnaire. Despite this, there was a differential reponse rate between Aboriginal services (response rate of 13%) and mainstream services (response rate of 33%). Because both groups differ in meaningful ways, this may have introduced nonresponse bias to the study.

No rigorous follow-up was performed and no payments for time were offered for participation in the study, potentially contributing to the relatively low response rate. It was anticipated that services with specific interest or experience in fall prevention for older Aboriginal people would respond to the questionnaire. Despite this, because of the low response rate, the results of this study cannot be used to provide a definitive picture of fall prevention services for Aboriginal people in NSW.

Future research investigating the views of older Aboriginal people towards fall prevention and healthy ageing is needed to inform the content and delivery of an appropriate fall prevention intervention. The project team investigated this through Yarning Circles held with older Aboriginal community members, in a separate study.25

Conclusion

This study identifies a gap in the availability of fall prevention programs specifically designed for, and delivered to, older Aboriginal people in NSW. A variety of mainstream fall prevention programs are delivered across the state; however, there were multiple barriers to attendance by older Aboriginal people, with a lack of cultural competency highlighted as a key factor. Although service providers working in Aboriginal services felt that fall prevention programs would benefit their older Aboriginal clientele, limits on funding, difficulties in communication between existing health services and a lack of available Aboriginal health staff prevented them from being able to offer appropriate programs. Further consultation with older Aboriginal people is necessary to determine how an acceptable and effective program can be designed and delivered.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the participation of Aboriginal people and Elders in this study. All contributions made are extremely valued and appreciated.

The authors would additionally like to thank all members of the project’s steering committee for their input and guidance over the duration of the project. This project was funded by the NSW Health Aboriginal Injury Prevention and Safety Promotion Demonstration Grants Program.

Copyright:

© 2016 Lukaszyk et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Experimental estimates and projections, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: 1991 to 2021. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2009 [cited 2016 Oct 10]. Available from: www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/27B5997509AF75AECA25762A001D0337/$File/32380_1991%20to%202021.pdf

- 2. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Estimates and projections, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: 2001 to 2026. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2016 [cited 2016 Aug 2]. Available from: www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/375E740A54DFB6AFCA257CC900143F09/$File/32380.pdf

- 3. Bradley C. Hospitalisations due to falls by older people, Australia, 2009–10. Canberra: AIHW; 2013 [cited 2016 Oct 19]. Available from: emsas.com.au/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/14820.pdf

- 4. Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence. The health of Aboriginal people of NSW: report of the Chief Health Officer. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2012 [cited 2016 Oct 10]. Available from: www.health.nsw.gov.au/epidemiology/Publications/Aboriginal-Health-CHO-report.pdf

- 5. Boufous S, Ivers R, Senserrick T, Martiniuk A, Clapham K. Underlying causes and effects of injury in Australian Aboriginal populations: a rapid review. Sydney: Sax Institute; 2010 [cited 2016 Oct 10]. Available from: www.saxinstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/14_Boufous-et-al.-FINAL-FOR-PUBLICATION.pdf

- 6. Bradley C. Trends in hospitalisations due to falls by older people, Australia 1999–00 to 2010–11. Canberra: AIHW; 2013 [cited 2016 Oct 10]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=60129543591

- 7. New South Wales Falls Prevention Network. Active & healthy. Sydney: Staying Active and On Your Feet; 2014 [cited 2015 Jul 1] [about 4 screens]. Available from: www.activeandhealthy.nsw.gov.au/

- 8. Yardley L, Donovan-Hall M, Francis K, Todd C. Older people's views of advice about falls prevention: a qualitative study. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(4):508–17. CrossRef | PubMed

- 9. Aspin C, Brown N, Jowsey T, Yen L, Leeder S. Strategic approaches to enhanced health service delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with chronic illness: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):143. CrossRef | PubMed

- 10. Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15. CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. CrossRef | PubMed

- 13. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Prev Med. 2007;45(4):247–51. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. Michie S. Which behaviour change approach should I choose? An introduction to the behaviour change wheel. Melbourne: BehaviourWorks Australia; 2012 [cited 2016 Oct 11]. Available from: www.behaviourworksaustralia.org/V2/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/SusanMichie2.pdf

- 15. Robertson MC, Devlin N, Gardner MM, Campbell AJ. Effectiveness and economic evaluation of a nurse delivered home exercise programme to prevent falls. 1: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322(7288):697–701. CrossRef | PubMed

- 16. Stevens M, Holman CD, Bennett N, de Klerk N. Preventing falls in older people: outcome evaluation of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(11):1448–55. CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. Shannon C, Longbottom H. Capacity development in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health service delivery: case studies. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2004 [cited 2016 Oct 10]. Available from: www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-oatsih-pubs-reviewphc.htm/$FILE/4capacity.pdf

- 18. Dwyer J, O'Donnell K, Laviole J, Marlina U, Sullivan P. The overburden report: contracting for Indigenous health services. Adelaide: Flinders University and Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2009 [cited 2016 Oct 10]. Available from: www.flinders.edu.au/medicine/fms/sites/health_care_management/documents/Overburden%20Report_contracting%20for%20Indigenous%20Health%20Services.pdf

- 19. Trewin D, Madden R. The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2005 [cited 2016 Oct 10]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=10737418955

- 20. Bird M, Henderson C. Recognising and enhancing the role of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers in general practice. Aborig Isl Health Work J. 2005;29(3):32–4. Article

- 21. Hayman NE, White NE, Spurling GK. Improving Indigenous patients’ access to mainstream health services: the Inala experience. Med J Aust. 2009;190(10):604–6. PubMed

- 22. Mitchell M, Hussey LM. The Aboriginal health worker. Med J Aust. 2006;184(10):529–30. PubMed

- 23. Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet. Workforce development. Perth: Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet; 2015. Workforce development; 2016 [cited 2016 Aug 9] [about 5 screens]. Available from: www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/health-infrastructure/health-workers/health-workers-workforce/workforce-development#fnl-5

- 24. Sherrington C, Tiedemann A, Fairhall N, Close JC, Lord SR. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated meta-analysis and best practice recommendations. N S W Public Health Bull. 2011;22(3–4):78–83. CrossRef | PubMed

- 25. Lukaszyk C, Coombes J, Turner NJ, Hillmann E, Keay L, Tiedemann A, et al. Yarning about fall prevention: community consultation to discuss falls and appropriate approaches to fall prevention with older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Implement Sci. (Under review, copy on file with author).