Abstract

The New South Wales School Students Health Behaviours Survey (2014) reported a substantial reduction in students aged 12–17 years reporting that they had ever consumed alcohol, from 82.7% in 2005 to 65.1% in 2014. Similar downward trends are reported nationally and internationally. Although overall consumption is declining, national recommendations maintain that it is safest for young people to not drink at all; however, 17% of all young people in Australia consumed alcohol in the past 7 days, with 6% consuming at a significant risk of harm. The factors that influence young people’s uptake of alcohol are complex, including biological and broader social factors. This paper identifies some of the diverse influences on young people’s alcohol consumption, and policies and programs that support healthy behaviours.

Full text

Introduction

For young people younger than 18 years, not drinking alcohol is the safest option.1 National guidelines also recommend delaying the first drink of alcohol for young people aged 15–17 years. A promising picture is emerging in line with these recommendations, with clear trends of young Australians delaying their first use of alcohol and refraining from alcohol consumption entirely.

National and international alcohol consumption patterns in young people

The National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2013 reported a decrease in the proportion of young people (aged 12–17 years) who had ever consumed a full serve of alcohol from 41% in 2010 to 32% in 2013. This coincides with a rise in the average age of alcohol initiation (having consumed at least one full serve of alcohol) for younger people from 14.4 years in 1998 to 15.7 years in 2013.2,3

Internationally, there is evidence of similar trends with young people not consuming alcohol. For example, in England, nearly 40% of school students in 2014 aged 11–15 years reported having had an alcoholic drink compared with nearly 60% in 2005.4 Similarly, in the US in 2013, 66% of 9th to 12th grade students had ever had one serve of alcohol in their life, compared with 75% in 2005.5

However, young people who do consume alcohol are at high risk of experiencing harms because of excessive consumption of alcohol on a single occasion – that is, consuming more than four standard drinks on an occasion when they consume alcohol.

The 2011 Australian secondary school students’ alcohol and drug survey reported that 17.4% of all students consumed a whole standard alcoholic drink in the past 7 days, and 6.4% of all students drank at risk of short-term harm (consuming more than four standard alcoholic drinks on any day in the past week).6 Short-term risks include hospitalisation from intoxication or injury, injury from alcohol-related violence or unwanted sexual activity.7

It is important to note the different methods used to measure adolescent alcohol consumption, in particular, consuming a few sips of alcohol versus consuming a whole alcoholic drink. Although there are some concerns with the test–retest reliability of self-reported age of first drink8, some argue that this should not preclude it from being a useful measure to understand the association between early onset drinking and later alcohol-related outcomes.

NSW alcohol consumption patterns in young people

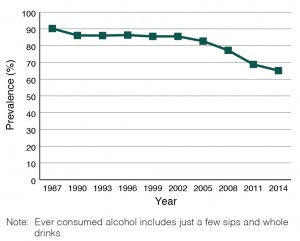

In New South Wales (NSW), a pattern similar to that in Australia as a whole has been observed, with a substantial reduction in students aged 12–17 years reporting that they had ever consumed alcohol (including just a few sips) from 82.7% in 2005 to 65.1% in 2014. However, in NSW, 5.7% of all students reported consuming four or more drinks on at least 1 day in the past 7 days, placing them at risk of alcohol-related injury on the occasions when this occurred.9

Figure 1. Ever consumed alcohol, people aged 12–17 years, NSW, 1987–2014

Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics suggest that young Aboriginal people (15–17 years) are equally likely as non-Aboriginal people to not consume alcohol.10

Risk and protective factors for alcohol consumption in young people

These trends in alcohol initiation and consumption are promising; therefore, it is important to consider the possible factors that have contributed to the changes, which are likely to be multiple and interacting, including the broader policy and social context. A well-established body of literature supports the importance of genetic influences in substance abuse and dependency, as well as epigenetic factors that influence the expression of genes, noting fetal alcohol spectrum disorders as an example.11

In addition to genetic predisposition, factors that influence the uptake and consumption of alcohol in young people are complex. From a life span perspective, risk factors include parental substance use during and after pregnancy, a child’s temperament, and caregiver–child attachment qualities. Life span stressors include transition through primary and secondary school periods where biological, behavioural and emotional regulation development is important, along with development of social support, positive self-esteem and interpersonal relationships.12 There are biological reasons to delay onset of alcohol consumption, including adverse effects on brain development, which have been seen primarily in animal models to date.1 In the longer term, early-age alcohol use is a risk factor associated with the development of dependence and high-risk drinking13, and use of other substances later in life.14

Protective factors such as parental modelling, limiting availability of alcohol to the child, parental monitoring, parent–child relationship quality, parental involvement and general communication have been found to be related to delayed alcohol initiation.15 However, social contexts that provide easier access to alcohol and parental supply of alcohol may also increase the likelihood of young people’s risky drinking over time. This is because a barrier to drinking alcohol is removed, which challenges the perception that parental provision of alcohol is protective.16

Livingston explores the phenomenon of increasing numbers of young people in Australia and internationally choosing to not drink alcohol.17 Livingston argues that waves of rising and falling consumption patterns (both in Australia and internationally) could be related to increases in alcohol-related harm, followed by increases in social concern and then subsequent reductions in consumption, which may be related to more restrictive parental alcohol supply to adolescents. Livingston also suggests other factors such as changing youth leisure patterns (e.g. increased time spent on the internet), and the increasing cultural diversity of Australia’s population may also play a role.

Drivers of change

There is good evidence that strategies such as taxation and reductions in supply are likely to have a significant impact on alcohol consumption, including in young people.18 For example, the 2008 ready-to-drink (‘alcopops’) tax was associated with declining emergency department presentations in young- to middle-aged people, including underage drinkers.19

The NSW Government regulates the sale and supply of liquor through the Liquor Act 2007. The Liquor Regulations 2008 has recently strengthened restrictions on hotels, clubs and packaged liquor through the NSW Liquor Amendment Act 2014, which imposed 1.30 am venue lockouts, 3 am last-liquor sales in the Sydney Business District Entertainment precinct and state-wide 10 pm closing time for packaged liquor businesses.

Other alcohol-related harm minimisation measures outlined in the legislation include liquor accords, identity scanners and responsible service of alcohol training, although the evidence supporting these measures is not strong.20 In NSW, successive governments have also implemented stronger laws to reduce underage drinking through parental supply.

The NSW Department of Education has an extensive drug and alcohol curriculum across the school-age population through the ‘Personal development, health and physical education’ curriculum. This includes the Crossroads program for students completing Years 11 and 12, which provides them with the skills to address significant changes and challenges, including drug and alcohol issues.

Family-focused programs that support parents to reflect on their parenting styles and implement changes are also valuable strategies.21 The NSW Government’s ‘whole of family’ teams provide services to parents where there are multiple needs of mental health and drug and alcohol concerns. Other programs include Brighter Futures (targeted early intervention), Getting It Together (focus on vulnerable young people) and family support programs through Family and Community Services NSW and Family Drug Support.

NSW Health has established the Drug and Alcohol Population and Community Programs Unit (DAPCP), with a dedicated focus on drug and alcohol population prevention and harm minimisation, including for young people (see Your Room). The DAPCP delivers programs for young people through peer-led approaches, schools-based interventions and family support. The DAPCP also delivers a multicomponent intervention for Aboriginal women and their partners, young people, and health professionals to raise awareness of the risk of alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Online interventions for risky alcohol consumption are a priority, and NSW Health has developed an alcohol program for the Get Healthy Information & Coaching Service, which delivers support to adults to reduce harmful alcohol consumption.

Emerging strategies

The NSW Ministry of Health will comprehensively outline its emerging priorities to address alcohol and other drug use in young people in the Alcohol & Other Drug Strategic Plan 2016–2021, which is expected to be released in late 2016. The plan will outline actions for:

- Keeping people healthy and out of hospital

- Providing high-quality treatment and integrated clinical care

- Building the capacity of the system and prevention.

The plan will also include an increased focus on family support, alcohol consumption in preconception and pregnancy, and community engagement. The recently announced NSW Government’s ‘drug and alcohol package’ has a strong focus on expanding access to youth-specific treatment services, improved support for families and an early intervention innovation fund. The DAPCP is also undertaking preliminary work on an Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy for a comprehensive, integrated, multidimensional strategy to improve alcohol culture in NSW, including for young people. This NSW work will align with the Australian Government’s draft National Drug Strategy (2016–2025).

Conclusions

NSW, Australian and international data suggest an increase in the proportion of students choosing to not drink alcohol and delaying initiation. However, there remains a substantial proportion of students drinking outside of recommendations, and a small proportion drinking at high-risk levels. The complex array of factors that drive the uptake of alcohol consumption are addressed through a comprehensive range of government programs that aim to better equip families to support young people through significant transition periods, and support healthy choices in regards to alcohol and other substances. Further research is warranted on the factors that are driving the downward trends to support a sustained effort by government and other agencies to maintain these trends, and deliver programs to the most at-risk young people who are still consuming alcohol at harmful rates.

Copyright:

© 2016 Moore et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2009 [cited 2016 Aug 29]. Available from: www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/ds10-alcohol.pdf

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National drug strategy household survey detailed report: 2013. Canberra: AIHW; 2014 [cited 2016 Aug 29]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=60129549848

- 3. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2010 National drug strategy household survey report. Canberra: AIHW; 2011 [cited 2016 Aug 29]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=10737421139&libID=10737421138

- 4. Fuller E, Agalioti-Sgompou V, Christie S, Fiorini P, Hawkins V, Hinchliffe S, et al. Survey of smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England in 2014. Leeds: Health and Social Care Information Centre and Lifestyles Statistics; 2015 [cited 2016 Aug 29]. Available from: digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB17879/smok-drin-drug-youn-peop-eng-2014-rep.pdf

- 5. National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. Youth risk behaviour survey. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014 [cited 2016 Aug 29]. Available from: www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/us_alcohol_trend_yrbs.pdf

- 6. White V, Bariola E. Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco, alcohol, and over-the-counter and illicit substances in 2011. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2012 [cited 2016 Aug 29]. Available from: www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/Publishing.nsf/content/BCBF6B2C638E1202CA257ACD0020E35C/$File/National%20Report_FINAL_ASSAD_7.12.pdf

- 7. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Young Australians: their health and wellbeing 2011. Canberra: AIHW; 2011 [cited 2016 Aug 29]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=10737419259

- 8. Hingson R, Zha W, White A. The usefulness of ‘age at first drink’ as a concept in alcohol research and prevention. Addiction. 2016;111(6):968–70. CrossRef | PubMed

- 9. Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence. New South Wales school students health behaviours survey: 2014 Report. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2016 [cited 2016 Aug 29]. Available from: www.health.nsw.gov.au/surveys/student/Publications/student-health-survey-2014.pdf

- 10. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health survey: first results, Australia, 2012–13. Canberra: ABS; 2013 [cited 2016 Aug 29]. Available from: www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/4727.0.55.001

- 11. Mason S, Zhou FC. Editorial: genetics and epigenetics of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Front Genet. 2015;6:146. CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. Spooner C, Hetherington K. Social determinants of drug use. Technical report number 228. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales; 2004 [cited 2016 Aug 29]. Available from: ndarc.med.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/ndarc/resources/TR.228.pdf

- 13. Liang W, Chiktritzhs T. Age at first alcohol use and risk of heavy alcohol use: a population-based study. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:721761. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. King K, Chassin L. A prospective study of the effects of age of initiation of alcohol and drug use on young adult substance dependence. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(2):256–65. CrossRef | PubMed

- 15. Ryan SM, Jorm AF, Lubman DL. Parental factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(9)774–83. CrossRef | PubMed

- 16. Kaynak O, Winters KC, Cacciola J, Kirby K, Arria AM. Providing alcohol for underage youth: what messages should we be sending parents? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75(4):590–605. CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. Livingston M. Understanding recent trends in Australian alcohol consumption. Canberra: Centre for Alcohol Policy Research, Foundation for Alcohol Research & Education; 2015 [cited 2016 Aug 29]. Available from: www.fare.org.au/wp-content/uploads/research/Understanding-recent-trends-in-Australian-alcohol-consumption.pdf

- 18. Chikritzhs T, Gray D, Saggers S. Restrictions on the sale and supply of alcohol: evidence and outcomes. Perth: National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University of Technology; 2007 [cited 2016 Aug 29]. Available from: ndri.curtin.edu.au/local/docs/pdf/publications/R207.pdf

- 19. Gale M, Muscatello D, Dinh M, Byrnes J, Shakeshaft A, Hayen A, et al. Alcopops, taxation and harm: a segmented time series analysis of emergency department presentations. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:468. CrossRef | PubMed

- 20. Livingston M, Wilkinson M, Room R. Community impact of liquor licences: an Evidence Check brokered by the Sax Institute for the NSW Ministry of Health. Sydney: The Sax Institute; 2015 [cited 2016 Sep 15]. Available from: www.adf.org.au/images/evidence-check-community-impact-liquor-licences.pdf

- 21. Ryan SM, Jorm AF, Lubman DL. Parental factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(9):774–783. CrossRef | PubMed