Abstract

Overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence are associated with adverse health consequences throughout the lifecourse. Rates of childhood overweight and obesity have reached alarming proportions in many countries and pose an urgent and serious challenge. Policy responses across the world have been piecemeal. Evidence based policy actions and interventions are available to build a comprehensive approach to overweight and obesity but, in most countries, a narrow selection of interventions are chosen, often implemented over short time periods and typically with small-scale investment. The most cost-effective policy actions are rarely selected, or only partially adopted. Genuinely comprehensive, long-term population-wide approaches are scant. Leading-edge fiscal and regulatory strategies face aggressive, often effective, opposition from lobby groups. We outline the policy actions, governance and accountability mechanisms needed to tackle this global epidemic.

Full text

Introduction

Overweight and obesity carry profound health and economic burdens; as body mass index (BMI) increases throughout the life course, so does the prevalence of comorbid conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease and some cancers.1 More immediate adverse health outcomes of childhood obesity include social and mental health concerns during adolescence.2

Children and adolescents who are obese are five times more likely to be obese in adulthood than those who were not obese, representing a lifelong personal burden and long-term societal impacts. Around 55% of children who are obese will be obese in adolescence, around 80% of adolescents who are obese will still be obese in young adulthood, and around 70% will be obese over age 30.3 In 2016, among 5–19-year-olds, 50 million girls and 74 million boys worldwide were estimated to be obese, with an additional 213 million children and adolescents in the overweight category.4

Conversely, the majority of adults who are obese were not obese in childhood or adolescence, so early prevention will only partially reduce the prevalence of adult obesity. Adulthood is where much of the associated morbidity and healthcare cost burden occurs3; indeed, a lifelong approach was recommended in the Foresight report5 – a UK Government analysis which brought together system-mapping and scenario-development methodologies to generate policy response options to obesity. Expert commentary has also revisited this life-course theme.6

Nonetheless, action to prevent and reduce overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence, to reduce both societal and personal burdens, is undoubtedly needed, and likely has more immediate public and political appeal than dealing with adult obesity. Policy makers can also consider the universal policy actions that are relevant for children but which would also confer benefits later in the life course, such as fiscal strategies and limitations on unhealthy product marketing.

Policy actions to address obesity

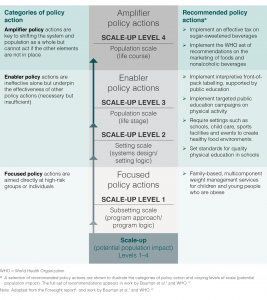

Evidence reviews from reputable independent organisations, represented selectively in Figure 1, are consistent in their recommendations on policy actions and interventions to address overweight and obesity among children and adolescents.7,8 The reviews are clear that no single action alone will suffice; scaled-up, comprehensive, multisectoral strategies are needed. The necessary suite of policies is described in the NOURISHING framework and food policy package for healthy diets and the prevention of obesity and diet-related noncommunicable diseases9, and in the INFORMAS framework.10 The NOURISHING framework comprises three broad categories of policies designed for: 1) food environments; 2) food systems; and 3) behaviour change communication.9 Although the noted policy actions are important and necessary to address obesity, policy action (especially fiscal policy) to reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages has been suggested as the single most cost-effective intervention with respect to childhood obesity.11 Reducing marketing of energy-dense nutrient-poor foods to children has also been deemed highly cost-effective.7,11 We focus on these policy areas in particular in this paper. Fiscal strategies to reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and regulation of the marketing of unhealthy food and beverages feature prominently in the NOURISHING and INFORMAS policy frameworks, as well as in recent World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations.12

Figure 1. Categories of policy action, scale-up level and selected evidence based recommendations for policy actions to address overweight and obesity in children and adolescents (click to enlarge)

Despite consistent recommendations, the prominence of evidence based taxes and regulatory policy at the WHO and supranational level is reduced at country level to focus more on individual responsibility for childhood obesity prevention.2,4 The NOURISHING framework database shows that some progress has been made in the fiscal domain with 34 countries having some form of tax on sugar-sweetened beverages by October 201813; however, researchers have also noted the challenges faced in several countries such as the US, Denmark, South Africa and Fiji.14 By contrast, mandatory regulation of broadcast food advertising to children is in place in only 10 countries.13

Reluctance to embrace fiscal and regulatory policy may be partly attributable to extensive corporate political activity by the food and beverage industries. Certain industry tactics have been shown to potentially influence national or regional public health–related policies and programs to favour business interests at the expense of public health.15 The reluctance to implement policy may occur even in the presence of a groundswell of community advocacy, indicating the power of industry influence.16 Internal contradictions are evident when policy makers’ language of ‘crisis’ is used to describe the epidemic of childhood obesity, but not accompanied by commensurate policy action to address it.2 Our discussion of the limitations in fiscal and regulatory policy should not be taken to mean that other strategies are being well implemented; the verdict of ‘patchy progress on obesity prevention’ has been recorded by researchers17 and can now be verified in close to real time by examining the NOURISHING database.13

Strategic governance and accountability

The apparent ease with which industry lobby groups manage to advance their causes at the expense of public health18 highlights the need for policy to encompass not only the actions and interventions directed at the population but also the broader governance, coordination and accountability mechanisms needed to protect the public interest. These mechanisms were clearly elucidated in the Foresight report, which sets out two instructive checklists: 1) 14 criteria for an effective obesity strategy (pp 133–5); and 2) 10 criteria for successful management and coordination of the strategy by government (pp 138–9), which we have summarised in Figure 2.5 These criteria for effective policy actions and for effective policy governance, coordination and accountability were arguably embedded in the approach used for England’s (£372 million over 3 years) cross‐government strategy to tackle obesity – Healthy Weight, Healthy Lives (HWHL), except that a senior bureaucrat committee replaced the Cabinet-level committee stipulated in Foresight.19 Subsequent analysis of the development and implementation of HWHL stressed the importance of adequate funding and of the clear governance structure. In our view, the analysis serves to validate the Foresight criteria, at least in the English context.20 The need for these mechanisms is reinforced by recent research, yet they appear to be neglected by most national governments.21

Figure 2. Criteria for effective policy actions targeting obesity, and for effective policy governance, coordination and accountability (click to enlarge)

Discussion

Notwithstanding the progress noted by others in this issue of the journal22,23, our assessment is that the requisite comprehensive policy actions and accountability mechanisms have yet to be implemented fully in any single country.17 We suggest four categories to examine such strategic error or failure: 1) shortcomings in strategy design; 2) investment failures; 3) inconsistent governance and accountability; and 4) underestimating the need for government intervention to address market failures.

Shortcomings in strategy design

Strategy design failure may arise through overreliance on too narrow a selection of actions or through implementation of less impactful, small-scale actions. An example of this is implementing popular educational and informational approaches – designed to target the knowledge and attitudes of individuals and thereby help them make ‘informed choices’ – but, critically, neglecting the powerful environmental and commercial determinants of obesity.17,24 Expecting secondary school–based physical activity programs to shift BMI and solve the obesity epidemic, and declaring them a failure when they inevitably achieve neither of these unrealistic goals, also falls into this category, doing a disservice both to obesity prevention and to the many other health and educational benefits of such physical activity programs. Education settings do have a potentially important strategic role in obesity prevention, given correct program specification and as part of a comprehensive portfolio.7

Investment failures

Investment failure arises when the necessary ‘dose’ (intensity and duration of actions) and comprehensiveness of the policy mix (‘upstream’ as well as ‘downstream’, universal as well as targeted, multisectoral and multisetting) are not achieved. Investment failure can occur if policies are:

- Unbalanced: overemphasis on less effective strategies, and/or

- Lightweight: omission of the most effective strategies, and/or

- Short term/spread thinly: insufficient resourcing for the necessary intensity and duration across the chosen policy mix.

Current understanding of the investment thresholds for strategies to attain population impact is imperfect, but this is often challenging in multistrategy complex interventions. Policy makers can make use of evidence to guide investment, where it exists25, while ensuring evaluation mechanisms are in place to improve knowledge where evidentiary guidance is weak.

Inconsistent governance and accountability

Inconsistency in governance and accountability can arise in a variety of ways5,21, including:

- Lack of transparency

- Noninclusion of civil society

- Naïveté about industry lobbying and failure to address conflict of interest with the public good

- Not having Office of Prime Minister/Cabinet-level support and coordination for cross-government policy

- Under-involvement of independent technical experts

- Not committing to a culture of continuous improvement

- Lack of coordination and organisation to ensure: 1) continuous monitoring of implementation; 2) regular strategic review of the scope and duration of components within an overall plan; and 3) synthesis of implementation monitoring data, strategic review status, new evidence and modelling to inform and guide policy decisions within an iterative systems-based approach.

Underestimation of the need for governments to address market failures

Market failures have three main causes – market power, asymmetric information and externalities; the latter two are most relevant here.26,27 The current market heavily favours short-term behavioural preferences (overconsumption/underactivity) over long-term preferences (healthy consumption/active living). In an environment where unhealthy marketing is a ubiquitous backdrop to daily life (asymmetric information), expecting adults, let alone children, to make food and activity choices in their own best long-term interests is likely to be ineffective. Externalities (additional impacts) involve the social costs and benefits of certain forms of consumption not being fully reflected in their private costs and benefits to individual consumers26 – the cost of sugar-sweetened beverages may not fully reflect adverse societal impacts from their excessive consumption. Significant government reappraisal is required to correct such market failure.27 Government intervention to establish accessible physical activity infrastructure for walking, cycling and play, and especially to curtail unhealthy marketing that affects children, is vital. Without it, remaining obesity policy actions are diminished7,21,27,28, fail to tackle commercial determinants of health24, and are unlikely to reduce childhood obesity.

Conclusions

Despite progress, recommended policy actions have not been substantially implemented to tackle an epidemic that needs comprehensive, intensive and sustained efforts. It is necessary but insufficient for governments to select from the menu of obesity policy actions recommended by WHO and independent scientific syntheses. Success requires not only a comprehensive suite of policy actions but also the integration of mechanisms to prevent four types of strategic failure: 1) shortcomings in strategy design; 2) investment failure; 3) inconsistent governance and accountability; and 4) underestimating the robust government intervention needed to address market failure.

Acknowledgements

The evidence review by Bauman et al. was funded by the NSW Ministry of Health, brokered by the Sax Institute.

Peer review and provenance

Externally peer reviewed, commissioned.

Copyright:

© 2019 Bellew et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88. CrossRef | PubMed

- 2. Black N, Hughes R, Jones AM. The health care costs of childhood obesity in Australia: an instrumental variables approach. Econ Hum Biol. 2018;31:1–13. CrossRef | PubMed

- 3. Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17(2):95–107. CrossRef | PubMed

- 4. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2627–42. CrossRef | PubMed

- 5. Butland B, Jebb S, Kopelman P, McPherson K, Thomas S, Mardell J, Parry V. Foresight. Tackling obesities: future choices – project report (2nd Edition). London, UK: Government Office for Science; 2007 [cited 2019 Jan 24]. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/287937/07-1184x-tackling-obesities-future-choices-report.pdf

- 6. Leeder S. Two roads converge in a yellow wood. Canberra: Public Health Association of Australia; 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 24]. Available from: www.phaa.net.au/documents/item/2649

- 7. Bauman A, Bellew B, Boylan S, Crane M, Foley B, Gill T, et al. Obesity prevention in children and young people aged 0–18 years: a rapid evidence review brokered by the Sax Institute. Sydney: University of Sydney; 2016 [cited 2019 Jan 24]. Available from: tinyurl.com/y735oxza

- 8. World Health Organization. Consideration of the evidence on childhood obesity for the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity: report of the ad hoc working group on science and evidence for ending childhood obesity. Geneva: WHO; 2016 [cited 2019 Feb 5]. Available from: apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/206549/1/9789241565332_eng.pdf

- 9. Hawkes C, Jewell J, Allen K. A food policy package for healthy diets and the prevention of obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases: the NOURISHING framework. Obes Rev. 2013;14(S2):159–68. CrossRef | PubMed

- 10. Swinburn B, Sacks G, Vandevijvere S, Kumanyika S, Lobstein T, Neal B, et al. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): overview and key principles. Obes Rev. 2013;14(S1):1–12. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Gortmaker SL, Wang YC, Long MW, Giles CM, Ward ZJ, Barrett JL, et al. Three interventions that reduce childhood obesity are projected to save more than they cost to implement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(11):1932–9. CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. World Health Organization. Report of the commission on ending childhood obesity. Implementation plan: executive summary. Geneva: WHO; 2017 [cited 2019 Feb 5]. Available from: apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259349/WHO-NMH-PND-ECHO-17.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- 13. World Cancer Research Fund International. London: World Cancer Research Fund. NOURISHING Database; 2018 [cited 2019 Feb 5]. Available from: www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-database

- 14. Thow AM, Downs SM, Mayes C, Trevena H, Waqanivalu T, Cawley J. Fiscal policy to improve diets and prevent noncommunicable diseases: from recommendations to action. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96(3):201–10. CrossRef | PubMed

- 15. Mialon M, Swinburn B, Allender S, Sacks G. 'Maximising shareholder value': a detailed insight into the corporate political activity of the Australian food industry. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2017;41(2):165–71. CrossRef | PubMed

- 16. Sundborn G, Thornley S, Beaglehole R, Bezzant N. Policy brief: a sugary drink tax for New Zealand and 10,000-strong petition snubbed by minister of health and national government. N Z Med J. 2017;130(1462):114–6. Article

- 17. Roberto CA, Swinburn B, Hawkes C, Huang TT, Costa SA, Ashe M, et al. Patchy progress on obesity prevention: emerging examples, entrenched barriers, and new thinking. Lancet. 2015;385(9985):2400–9. CrossRef | PubMed

- 18. Han E. Beverages industry praises itself for turning politicians away from sugar tax. Sydney Morning Herald; 2017 Oct 22 [cited 2019 Feb 7]. Available from: www.smh.com.au/healthcare/beverages-industry-praises-itself-for-turning-politicians-away-from-sugar-tax-20171020-gz520t.html

- 19. Jebb SA, Aveyard PN, Hawkes C. The evolution of policy and actions to tackle obesity in England. Obes Rev. 2013;14(S2):42–59. CrossRef | PubMed

- 20. Hawkes C, Ahern AL, Jebb SA. A stakeholder analysis of the perceived outcomes of developing and implementing England's obesity strategy 2008–2011. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:441. CrossRef | PubMed

- 21. Swinburn B, Kraak V, Rutter H, Vandevijvere S, Lobstein T, Sacks G, et al. Strengthening of accountability systems to create healthy food environments and reduce global obesity. Lancet. 2015;385(9986):2534–45. CrossRef | PubMed

- 22. Rissel C, Innes-Hughes C, Thomas M, Wolfenden L. Reflections on the NSW Healthy Children Initiative: a comprehensive, state-delivered childhood obesity prevention initiative. Public Health Res Pract. 2019;29(1):e2911908. CrossRef

- 23. Love P, Laws R, Hesketh KD, Campbell KJ. Lessons on early childhood obesity prevention interventions from the Victorian Infant Program. Public Health Res Pract. 2019;29(1):e2911904. CrossRef

- 24. Kickbusch I, Allen L, Franz C. The commercial determinants of health. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(12):e895–e6. CrossRef | PubMed

- 25. Wiggers J, Wolfenden L, Campbell E, Gillham K, Bell C, Sutherland R, et al. Good for kids, good for life, 2006–2010: evaluation report. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2013 [cited 2019 Feb 5]. Available from: www.health.nsw.gov.au/research/Publications/good-for-kids.pdf

- 26. Karnani A, McFerran B, Mukhopadhyay A. The obesity crisis as market failure: an analysis of systemic causes and corrective mechanisms. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research. 2016;1(3):445–70. CrossRef

- 27. Moodie R, Swinburn B, Richardson J, Somaini B. Childhood obesity – a sign of commercial success, but a market failure. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2006;1(3):133–8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 28. Vallgårda S. Childhood obesity policies – mighty concerns, meek reactions. Obes Rev. 2018;19(3):295–301. CrossRef | PubMed