Abstract

Australia has experienced significant reductions in smoking rates in recent decades, and public health scrutiny is turning to how further gains will be made. Regulatory controls, such as licensing to reduce retailer density or limit tobacco proximity to schools or licensed premises, have been suggested by some public health advocates as appropriate next steps.

This paper summarises best-practice evidence in relation to tobacco retailer regulation, noting measures undertaken in New South Wales (NSW).

Research on controlling the display of tobacco products and supply of tobacco to minors is well established. The evidence shows that a combination of licensing, enforcement, education, promotion restrictions at the point of sale and a well-funded compliance program to prevent sales to minors is a best-practice approach to tobacco retail regulation. The evidence for other measures – such as restricting the number of retail outlets, and restricting how and where tobacco is sold – is far less developed. There is insufficient evidence to determine if a positive licensing system and controls on the density and location of tobacco outlets would be effective in the Australian context.

More evidence is required from jurisdictions that have implemented a positive licensing scheme to evaluate the effect of such schemes on smoking rates, the potential cost benefits and any unintended consequences.

Full text

Introduction

Preventing and reducing smoking in New South Wales (NSW), particularly among young people, is a key priority for the State Government. The NSW 2021 plan sets targets to reduce smoking rates by:

- 3% by 2015 for non-Aboriginal people, and 4% by 2015 for Aboriginal people

- 0.5% per year for non-Aboriginal pregnant women, and 2% per year for pregnant Aboriginal women.

The Government’s approach to tobacco control includes quit smoking campaigns, smoking cessation services, smoke-free environment laws, promotion controls and regulation of the tobacco retail environment. These efforts are aimed at complementing federal tobacco control regulations in taxation, advertising and customs. NSW has made strong gains in reducing rates of current smoking among adults and young people, from 22.5% in 2002 to 15.6% in 2014 among adults, and from 13% in 2002 to 7.5% in 2011 among secondary school students. 1,2

The public health community is now considering how to further reduce smoking rates in NSW. One area receiving attention is tobacco retail regulation. Questions raised include whether existing regulatory controls are sufficient, and whether measures to reduce retailer density or limit tobacco proximity to schools or licensed premises should be pursued.

Tobacco retailing laws in NSW

The Public Health (Tobacco) Act 2008 (NSW) (the Act) makes it illegal to sell tobacco products to people under the age of 18. It is also illegal to sell nontobacco (e.g. herbal) smoking products to people under the age of 18. A range of point-of-sale provisions cover restrictions on tobacco advertising, promotions, packaging, display and sale locations, and require health warnings to be displayed at the point of sale. The Act includes a notification-based licensing scheme for tobacco retailers that requires all retailers who sell tobacco to be registered with the Government Licensing Service. NSW Health coordinates a program of random and complaints-based inspections of retailers to monitor compliance and enforce the law.

Tobacco product displays

Visible tobacco displays contribute to unplanned purchases3 and make quitting more difficult.4 A 2009 systematic review concluded that point-of-sale display bans are justifiable on the grounds that advertising has been clearly proven to influence children to initiate smoking, and that branding of packs is an important form of promotion.5

NSW bans the retail display of tobacco products. Retailers can provide plain text information on the price of products available, but there are limits on the colour and placement of such information. Plain text warnings are also required to be displayed at the point of sale about the health risks of smoking, the availability of cessation support and prohibitions on selling tobacco to minors.

Areas not addressed in the current mix of laws are the use of price boards to communicate brand reputation and popularity6, and display of graphic warnings at the point of sale. The extent to which the remaining point-of-sale marketing options and the presence of retail outlets themselves prompt tobacco purchases or sabotage quit attempts is unknown.

Sales to minors

Research findings are clear in this area: selective and regular enforcement of youth access laws can help prevent underage young people from smoking. To maximise the effect of legislation relating to sales to minors, a comprehensive retailer enforcement and compliance program is needed, including monitoring, use of underage undercover shoppers and reporting of violations.7 Training retailers to recognise fake identification may also help improve compliance.

It is illegal to sell cigarettes to minors in NSW, and fines of up to $110 000 apply. Significant decreases in adolescent smoking rates in parts of NSW are thought to be at least partially attributed to the positive effect of strict law enforcement (using undercover shoppers), retailer education and publicity of legislation relating to sales to minors.8

Licensing

Part IV of the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) encourages parties to the treaty to “endeavour to adopt and implement further measures including licensing, where appropriate, to control or regulate the production and distribution of tobacco products in order to prevent illicit trade”.9

Although the best available evidence supports a tobacco licensing scheme, debate remains about how best to design and implement such a scheme. To be effective, licensing schemes should include annual reporting requirements, retailer education and strong enforcement. Removal from the market should be a genuine consequence for violations of tobacco retailing laws and licensing conditions.10,11

Generally, licensing schemes for tobacco retailers are described as negative or positive:

- A negative scheme requires tobacco retailers to notify the government if they are selling tobacco through a registration system. Retailers do not need to prove their suitability to sell tobacco. There may or may not be a fee involved

- A positive scheme requires tobacco retailers to apply for and receive a licence before selling tobacco products. In most cases, these schemes involve fees for application and annual renewal. Positive schemes may be used to vet potential retailers.

Both positive and negative schemes can provide accurate information about tobacco retailers to assist with implementing retail compliance monitoring and enforcement programs. Both types of schemes may involve penalties for retailers who breach retailing laws (e.g. do not register or obtain a licence). Both types of licensing systems can revoke the right to sell tobacco if ongoing breaches are observed.

Australia has a variety of tobacco licensing schemes. Victoria and Queensland do not require retailers to be licensed at all, while NSW, the Australian Capital Territory, Tasmania, the Northern Territory, Western Australia and South Australia have implemented different types of licensing schemes (Table 1).

Table 1. Tobacco retail licensing schemes in Australia

Please help us improve Web CIPHER by answering the three quick questions below |

Type of scheme | Cost of licence | Suitability assessment or requirements |

| ACT | Positive | $200/year | No, but refusal is possible if the applicant does not understand their obligations or has been convicted for sale of tobacco to minors |

| NSW | Negative | NA | No |

| NT | Positive | $222/year | Police criminal history check |

| QLD | No scheme | NA | NA |

| SA | Positive | $253/year | No |

| TAS | Positive | $306/year | No, but department should be satisfied that the applicant is over 18 years old and likely to comply with the legislation |

| VIC | No scheme | NA | NA |

| WA | Positive | $204−$510/year | No, but employees must be trained about not selling tobacco products and smoking implements to minors |

NA = not applicable

Proponents of positive licensing maintain that the availability of tobacco reduces or compromises quit attempts by smokers, and a positive scheme may be used to restrict the number, type and location of tobacco retailers. As of January 2015, no Australian jurisdiction had attempted to include number, type or location restrictions in their tobacco licensing schemes. A small body of work addressing these supply-side issues has begun to emerge and is summarised below. Given that very few of these types of controls have been enacted, much of the research in this area is either descriptive, qualitative, or, if longitudinal, relatively short term.

Type of retail outlet

Australian research suggests that supermarkets and tobacconists (which discount tobacco products more than other tobacco retailers) encourage larger purchases and are equally frequented by both light and heavy smokers.12 Although it is largely unknown how limiting the types of outlets selling tobacco would affect smoking rates, it is well understood that consuming alcohol, especially in social settings like hotels and clubs, increases the amount of smoking and undermines quit attempts.13 A 2010 study of retail premises that sell tobacco products found that having cigarettes sold on the premises affected reported tobacco consumption in locations such as licensed clubs, hotels and bars, with 22.4% of smokers indicating they smoked a lot more, 17.2% smoked a little more, 50.1% smoked the same amount, and only 4.2% reporting that they smoked less.14

Tobacco retail density, distance to and location of outlet

Evidence in this area is largely from outside Australia, where advertising and retail point-of-sale display restrictions vary. The research consists of analysis of associations between tobacco retail outlet density, distance and type of outlet, and smoking rates and tobacco purchase patterns. Socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity have been found to be associated with tobacco retail outlet density, with studies showing that low socioeconomic neighbourhoods and areas with a higher number of residents from racial and ethnic minority groups have higher outlet density.15 Outlet density is associated with smoking by both adolescents and adults.16-18 Australian studies have replicated the link between low socioeconomic neighbourhoods and outlet density19 and have found associations between school location and outlet density.20 However, it is unclear whether retailers are establishing themselves in areas where schools are located, or whether schools are located in commercial areas with high general retail density. International studies suggest that tobacco outlet density and proximity to schools influence young people’s smoking attitudes, behaviour and tobacco purchasing.18, 21 It is unclear if these associations are a product of tobacco retailers responding to higher demand, or whether the increase in retail outlets also increases smoking rates in certain communities.

Very little has been published on the association between proximity and density of retail outlets and smoking cessation attempts, but there is some evidence to suggest that living close to a tobacco retailer negatively affects cessation efforts.22 It remains unclear whether the availability of tobacco affects the likelihood of smoking cessation.

In addition to the need for more generalisable evidence, a range of broader public health and social policy issues should be considered when weighing up the value of restricting location, proximity and density of tobacco retail outlets. Potential unintended consequences of concentrating tobacco sales in fewer, larger retailers include lower tobacco prices and smokers stockpiling large purchases. Finally, using geographically based laws as a real or perceived means to target the behaviour of particular socioeconomic or other vulnerable groups may be perceived as unfair or discriminatory.

Age of retail staff

The WHO FCTC recommends that tobacco products should not be sold by people aged under 18.9 This recommendation is aimed at both protecting children from handling tobacco products and thus being directly exposed to tobacco marketing, and reducing sales to minors. This approach has not been pursued in NSW because there is no local evidence of a correlation between sales to minors and tobacco retail employees aged under 18. There are also potential business and youth employment consequences relating to such measures.

Compliance monitoring and enforcement

Tobacco regulation requires well-funded and regular monitoring and enforcement by the responsible authority. Penalty infringement notices (on-the-spot fines) are a useful enforcement tool for strict liability retail offences. In NSW, authorised inspectors within Local Health District public health units undertake ongoing compliance monitoring and enforcement activities in relation to the Act, including:

- Providing education to support tobacco retailers to comply with the law

- Conducting inspections of retail outlets to check for appropriate signage, product display and retailer registration

- Counselling noncompliant retailers to rectify breaches on the spot, where appropriate

- Coordinating undercover shopping by minors to check if tobacco products are sold

- Issuing warning letters

- Initiating prosecutions for noncompliance for serious or repeat offences.

Under the Act, monetary fines can be issued to offenders, and repeat offenders may be prohibited from trading for 3−12 months.

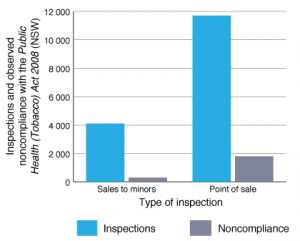

In NSW, more than 90% of retailers have been found to be compliant with sales to minors laws, and more than 80% are compliant with point-of-sale provisions (Figure 1). Authorised inspectors from NSW Health have advised that many breaches can be remedied on the spot.

Figure 1. Tobacco retailing inspections in NSW and noncompliance on first inspection, 2011–2014 (click to enlarge)

Note: Sales to minors inspection refers to Part 4, Division 1 of the Public Health (Tobacco) Act (NSW); a point-of-sale inspection refers to Parts 2, 3 and 5 of the Act.

Conclusion

Point-of-sale promotion restrictions and well-funded compliance programs to prevent sales to minors, combined with retailer licensing, education and enforcement, have the potential to further denormalise tobacco smoking and reduce its use. Licensing ensures that an accurate database of retailers is maintained to assist with coordination of compliance and enforcement programs.

Current NSW tobacco retailer laws generally accord with the evidence, and there is high overall compliance with tobacco retailing provisions. Further evidence is required to assess whether the public would benefit from more controls on the use of pricing boards, graphic warnings at the point of display, and a positive licensing system to control retailer density and proximity.

In particular, there is a lack of context-relevant evidence to assess whether a positive licensing scheme, and controls on the density and proximity of tobacco outlets to certain communities, schools or licensed venues, would reduce tobacco-related harm.

Copyright:

© 2015 Smyth et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. HealthStats NSW. Current smoking in adults by sex, NSW 2002 to 2014 [cited 2015 Jun 9]. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health. Available from: www.healthstats.nsw.gov.au/Indicator/beh_smo_age/beh_smo_age

- 2. HealthStats NSW. Current smoking by sex, secondary school students aged 12-17 years, NSW 1984 to 2011 [cited 2015 Jun]. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health. Available from: www.healthstats.nsw.gov.au/Indicator/beh_smostud_age/beh_smostud_age

- 3. Clattenburg EJ, Elf JL, Apelberg BJ. Unplanned cigarette purchases and tobacco point of sale advertising: a potential barrier to smoking cessation. Tob Control. 2013;22(6):376−81. CrossRef

- 4. Germain D, McCarthy M, Walsh RA. Smoker sensitivity to retail tobacco displays and quitting: a cohort study. Addiction. 2009;105:159−63. CrossRef

- 5. Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. NicotineTob Res. 2009;11(1):25−35. CrossRef

- 6. Wakefield M, Zacher M, Scollo M, Durkin S. Brand placement on price boards after tobacco display bans: A point-of-sale audit in Melbourne, Australia. Tob Control. 2012;21:589−92. CrossRef

- 7. DiFranza JR. Which interventions against the sale of tobacco to minors can be expected to reduce smoking? Tob Control. 2012;21(4):436−42. CrossRef

- 8. Tutt D, Bauer L, Difranza JR. Restricting the retail supply of tobacco to minors. J Public Health Policy. 2009;30(1):68−82. CrossRef

- 9. World Health Organization. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva: World Health Organization 2003 [cited 2015 Jun 15]. Available from: www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/

- 10. The Center for Tobacco Policy & Organizing, American Lung Association in California. Matrix of strong local tobacco retailer licensing ordinances. Sacramento: California Department of Public Health; 2012 [cited 2013 Feb 15]. Available from: center4tobaccopolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Matrix-of-Strong-Local-Tobacco-Retailer-Licensing-Ordinances-September-2013.pdf

- 11. McLaughlin I. License to kill?: tobacco retailer licensing as an effective enforcement tool. St Paul, MN: Tobacco Control Legal Consortium; 2010 [cited 2014 Jan 2]. Available from: publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/tclc-syn-retailer-2010.pdf

- 12. Burton S, Clark L, Heuler S, Bollerup J, Jackson K. Retail tobacco distribution in Australia: evidence for policy development. Australasian Marketing Journal. 2011;19(3):168−73. CrossRef

- 13. Piasecki T, Fiore M, McCarthy D, Baker T. Alcohol consumption, smoking urge, and reinforcing effects of cigarettes: an ecological study. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22(2):230−9. CrossRef

- 14. Paul CL, Mee KJ, Judd TM, Walsh RA, Tang A, Penman A, et al. Anywhere, anytime: retail access to tobacco in New South Wales and its potential impact on consumption and quitting. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(4):799−806. CrossRef

- 15. Yu D, Peterson NA, Sheffer MA, Reid RJ, Schnieder JE. Tobacco outlet density and demographics: analysing the relationships with a spatial regression approach. Public Health. 2010;124(7):412−6. CrossRef

- 16. Henriksen L, Feighery EC, Schleicher NC, Cowling DW, Kline RS, Fortmann SP. Is adolescent smoking related to the density and proximity of tobacco outlets and retail cigarette advertising near schools? Prev Med. 2008;47:210−14. CrossRef

- 17. Peterson NA, Lowe JB, Reid RJ. Tobacco outlet density, cigarette smoking prevalence, and demographics at the county level of analysis. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40(11):1627−35. CrossRef

- 18. Leatherdale ST, Strath JM. Tobacco retailer density surrounding schools and cigarette access behaviors among underage smoking students. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33(1):105−11. CrossRef

- 19. Kite J, Rissel C, Greenaway M, Williams K. Tobacco outlet density and social disadvantage in New South Wales, Australia. Tob Control. 2014;23(2):181−2. CrossRef

- 20. Marashi-Pour S, Cretikos M, Lyons C, Rose N, Jalaludin B, Smith J. The association between the density of retail tobacco outlets, individual smoking status, neighbourhood socioeconomic status and school locations in New South Wales, Australia. Spat Spatiotemporal Epidemiol. 2015;12:1−7. CrossRef

- 21. Loomis BR, Kim AE, Busey AH, Farrelly MC, Willett JG, Juster HR. The density of tobacco retailers and its association with attitudes toward smoking, exposure to point-of-sale tobacco advertising, cigarette purchasing, and smoking among New York youth. Prev Med. 2012;55:468−74. CrossRef

- 22. Reitzel LR, Cromley EK, Li Y, Cao Y, Dela Mater R, Mazas CA, et al. The effect of tobacco outlet density and proximity on smoking cessation. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(2):315−20. CrossRef