Abstract

Background and aim: Transition of asylum seekers from special-purpose health services to mainstream primary care is both necessary and difficult. This study explores the issues encountered by asylum seekers undergoing this transition in Sydney, Australia.

Methods: Qualitative semistructured interviews were conducted with nine asylum seeker patients and nine staff working in the sector.

Results: Asylum seekers faced significant challenges in the transition to mainstream primary care. Contributing factors included the complexity of health and immigration systems, the way in which asylum seeker–specific services provide care, lack of understanding and accommodation by mainstream general practioner (GP) services, asylum seekers’ own lack of understanding of the health system, mental illness, and social and financial pressures.

Conclusions: There is a need for better preparation of asylum seekers for the transition to mainstream primary care. Mainstream GPs and other providers need more education and support so that they can better accommodate the needs of asylum seeker patients. This is an important role for Australia’s refugee health services and Primary Health Networks.

Full text

Introduction

In 2016, an estimated 29 560 asylum seekers resided in Australia1, many of them in the community. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees considers asylum seekers to be “individuals who have sought international protection and whose claims for refugee status have not yet been determined”.1

Community-based asylum seekers face diverse and complex health problems, including infectious, nutritional and chronic noncommunicable diseases. Many asylum seekers have experienced torture and trauma, and develop psychological illnesses. Both physical and psychological conditions are often complicated by migration, asylum status and settlement.2 Despite a great need for health services, it has been recognised that many asylum seekers face significant barriers to accessing primary health care.3

Services for asylum seekers in Sydney

This paper defines ‘asylum seeker–specific health services’ as those that provide free primary health care to asylum seekers while they are ineligible for the Australian Government’s universal health insurance program, Medicare. In Sydney, New South Wales (NSW), there are two services: the Asylum Seekers Centre (ASC) and the NSW Refugee Health Service (RHS). The ASC is a nongovernment organisation that is dependent on donations and pro bono arrangements. It delivers free primary care, and social and financial support to asylum seekers, including more than 3000 health consultations and 450 free medications each year. The ASC employs one full-time health manager and two part-time registered nurses, and has pro bono arrangements with general practitioners (GPs), offering up to two primary care half-day sessions a week.4 Limited dental, physiotherapy, psychology and counselling services are available. The RHS provides health assessments and a GP clinic for Medicare-ineligible asylum seekers.5 The resources of both services are limited, necessitating the transition of patients to mainstream primary health care once they are eligible for Medicare.6,7

The Status Resolution Support Services (SRSS) program, funded by the Australian Government Department of Home Affairs (DHA), provides services to asylum seekers while their claims are being resolved. These may include financial assistance, housing, case management and access to schooling. SRSS providers are contracted by the DHA to administer payments and services.8

Transitions in care

The transition from asylum seeker–specific to mainstream primary care has proven to be difficult in a number of Australian and international contexts.6 The transition is often complicated by a lack of coordination between specialised and mainstream services9, reluctance among patients to transition10, difficulties in medical record transfer11, and the vulnerability of patients from a refugee background.12 However, the literature is limited and mostly considers refugees alone. The relevance of these issues to asylum seekers has not been fully established. Significantly, the views of asylum seekers themselves have not been comprehensively explored in the literature.

This study aims to inform and improve the transition process by exploring current issues through interviews with asylum seeker patients and healthcare providers, focused on the following research questions:

- What knowledge, attitudes and experiences exist among healthcare providers working with asylum seekers about transition from asylum seeker–specific primary care to ongoing mainstream primary health care services?

- What are the views and experiences of asylum seekers making the transition from asylum seeker–specific primary care to mainstream primary health care services?

Methods

Qualitative semistructured interviews were conducted with nine asylum seeker patients and nine healthcare providers working in the asylum seeker sector between April and August 2016.

Healthcare provider participants were recruited via the professional networks of the researchers and asylum seeker–specific health service staff. Participants were interviewed in person by author GF, who obtained written consent, and recorded and transcribed interviews verbatim. Topics included the health needs of asylum seekers, perceptions of the transition process and suggestions for improvement.

Asylum seeker participants were former or current clients of the ASC health service. Clients were invited to participate if they had been eligible for Medicare at some point and thus had transitioned from the ASC to a mainstream GP. Some clients had returned to the ASC because of loss of their Medicare entitlements. Purposive sampling was used to ensure diverse backgrounds and experiences. Clients were approached by an ASC nurse and informed about the study. Interested and eligible participants were interviewed at the ASC by GF. Verbal consent was obtained and handwritten notes were taken during the interview, rather than audio recording. This was agreed among the researchers to be preferable based on prior experience with asylum seeker clients, who could be suspicious of recordings and feel uncomfortable signing written documents. Participants who were known to clinic staff to not be fluent in English were offered an appropriate telephone interpreter; this was used in approximately half the interviews. Interviews focused on participants’ experiences of primary care and transition between services.

Interviews were carried out until thematic saturation was achieved. Descriptive qualitative methods were used to analyse the data. Transcripts were coded using an inductive approach to produce a list of themes with the aid of NVivo qualitative analysis software (Melbourne: QSR International; Version 11). Researchers reviewed transcripts collaboratively to discuss differences in coding and interpretation. A smaller list of cross-cutting themes was compiled and discussed, and data were recoded into these categories. These were presented to key stakeholders for feedback and discussion. The key stakeholders were from the same organisations as those of the healthcare provider participants, but they were not necessarily the same individuals who were interviewed.

Ethics approval was granted by the UNSW Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee Executive (HC15735).

Results

Relevant descriptive information was collected about the 18 participants, as shown in Tables 1 and 2. Each participant was identified using a code: S1–9 for healthcare providers and P1–9 for patients. Asylum seeker participants were from Cameroon, Guinea, Malaysia, Russia, Sri Lanka and Turkey.

Table 1. Characteristics of healthcare provider interview participants

| Characteristic | Number of participants (n = 9) |

| Organisation | |

| Asylum seeker–specific health service | 6 (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6) |

| Other health service | 3 (S7, S8, S9) |

| Age (years) | |

| 25–44 | 4 |

| 45–64 | 5 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 2 |

| Female | 7 |

| Time working in asylum seeker sector (years) | |

| <1 | 1 |

| 1–5 | 6 |

| ≥5 | 2 |

Table 2. Characteristics of asylum seeker interview participants

| Characteristic | Number of participants (n = 9) |

| Medicare status | |

| Eligible, recently transitioned to mainstream primary care | 5 (P1, P2, P3, P4, P5) |

| Eligible, still attending ASC; child recently transitioned to mainstream primary care | 2 (P6, P7) |

| No longer eligible, receiving primary care at ASC | 2 (P8, P9) |

| Age (years) | |

| 25–44 | 3 |

| 45–64 | 6 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 6 |

| Female | 3 |

| Time in Australia (years) | |

| <1 | 3 |

| 1–5 | 4 |

| ≥5 | 2 |

ASC = Asylum Seekers Centre

Process of transition

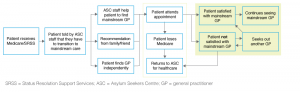

The ad hoc process of transition from asylum seeker–specific primary care to mainstream primary care was characterised through interviews and discussions with healthcare providers. Figure 1 outlines the general pathway described by participants.

Figure 1. Current transition pathway (click to enlarge)

Some patients readily accepted the need to transition, but others were strongly opposed, and some continued attending asylum seeker–specific primary care. For those willing to transition, a mainstream GP was identified through personal networks or with assistance from ASC staff. When staff helped patients to find GPs, they sought an appropriately located doctor who spoke the patient’s language and offered bulk-billing. Often, staff had ongoing contact with former patients to supply free medications; assist with booking appointments; and help with casework, employment guidance and food.

Many patients reported dissatisfaction with their mainstream GP, and some sought out a different GP or returned to asylum seeker–specific primary care. Other catalysts for returning to familiar services included loss of Medicare access or SRSS assistance and difficulty accessing mainstream care.

The ASC does not have an established process for transferring medical records to mainstream GPs. Staff usually waited until GPs made contact to ask for records. Most patients interviewed were unaware that transfer of records might be required, or did not know whether it had occurred.

Health system factors

Medicare instability

Interviewees regularly recounted examples of disrupted access to Medicare because of expiry or policy changes. Medicare instability resulted in severe physical and mental health consequences in numerous cases.

When my Medicare stopped, for a few months I didn’t take any medicines. There was damage to my eyes – I am now a little blind in my left eye here. (P8)

Somehow he had lost access to healthcare, and he ended up homeless [and] quite suicidal … It was that bureaucracy of not being able to access services that nearly caused him to lose his life. (S4)

These disruptions to access affected the abilities of asylum seekers to maintain independent interactions with the health system. The instability caused patients to return to asylum seeker–specific services, creating administrative and resource issues for already strained services.

Complexity of the health system and integration of services

Patients and healthcare providers communicated frustrations about the complexity of the health system and the difficulties encountered by patients learning to navigate it. Healthcare providers emphasised the need for changes in the system to better support patients with complex health and psychosocial issues.

It’s not the client’s job to fix themselves enough to be able to connect to the healthcare system – it’s our job as healthcare professionals to understand what’s going on for that client and do what’s needed to get that client the right kind of care. (S2)

Many patients received healthcare and support from multiple organisations, and difficulties arose in communication and integration between services. This resulted in patients receiving fragmented care, and fostered a sense of confusion.

I get a sense that he’s got a GP … who I think speaks his language, but he can’t tell me who that is. And therefore I can’t find out what work’s been done … or what treatment or testing is planned. (S8)

This affected the transition process significantly. Healthcare providers reported a smoother transition when there was an integrated transition with communication between all relevant services.

Asylum seeker–specific primary care services

The ASC provides a comprehensive and adaptable service model for patients, which helps foster a sense of inclusiveness and security. This model is quite different from mainstream general practice, in which set appointment times and procedures are the norm. Many healthcare providers acknowledged that these differences played a role in the development of over-reliance on asylum seeker–specific services, and compromised the opportunity for patients to develop vital health literacy skills required for independent interaction with mainstream services.

[At the ASC] there’s an open-door policy, some structure, but you can go and have lunch and then maybe see the nurse after lunch, you know. You can’t go into a GP practice and say I’m just going for a coffee and then I’ll be back in half an hour. (S1)

Some interviewees characterised the relationship between the ASC and its clients as one of parent and child. Although this demonstrates the strong sense of belonging and support that patients felt at the ASC, it also contributed to reluctance to transition to mainstream primary care.

I really appreciate the ASC. Everybody’s really good, as soon as I get here they ask about health, they take us on excursions even, they give us food. Like a mum and dad take care of their child, they do everything for us. (P2)

Transition to mainstream care presented an opportunity for patients to become more independent. This produced mixed feelings among many asylum seekers.

They were glad about getting protection, but upset about having to move on. And they said it was like graduating from primary school to high school, and they had to go out into this kind of bigger space where they didn’t know anyone, and had to do it themselves. (S2)

Many patients continued to attend asylum seeker–specific primary care despite having Medicare eligibility and theoretical access to mainstream primary care. Many who did transition required ongoing support to navigate the health system, organise appointments or access free medications. This burden of ongoing management affected the capacity of the service to meet the needs of new Medicare-ineligible patients.

Healthcare provider interviewees frequently identified the key role they could play in managing the transition process for and with patients. This involved two key components: managing communication with the mainstream health provider, and managing the expectations and skill development of the individual or family making the transition.

I think it’s up to [the ASC staff] to give a really sensible transition … to liaise with the caseworkers from other agencies, to explain what’s going on, to bring the client in as well, where we can, and find the right fit for a GP. (S1)

Mainstream primary care services

Understanding of asylum seekers’ health and entitlements

Interviewees frequently identified that mainstream GPs did not have a good understanding of issues affecting asylum seekers, including physical and mental health issues, social circumstances, and access to entitlements such as Medicare.

Factors reported to contribute to this lack of understanding included infrequent contact with asylum seekers, and sometimes dismissal of mental illnesses such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as political rather than mental health issues.

The lack of understanding frequently manifested as insensitivity to asylum seekers’ concerns.

I don’t understand him, he doesn’t seem to understand what I want … The way he approaches questions, I don’t like it. If I have headache and he ask me how long, I say I have headache 10 years, he says it’s probably nightmare and prescribes medications. I don’t feel at ease. The way he speaks to you is different to the doctor [at the ASC]. (P3)

Additionally, healthcare entitlements were often a source of confusion. SRSS providers had some clients who were eligible for primary care services despite not having Medicare access. Payments to healthcare providers were made by the SRSS provider, rather than by Medicare. The process of billing the SRSS provider and waiting for payment was unfamiliar and time-consuming for healthcare providers, resulting in resistance to taking on asylum seeker patients.

Patients and healthcare providers expressed the need to educate GPs about these issues. Some information sessions about refugee health issues had been organised by the local Primary Health Network (PHN) and the RHS, but attendance at these was low.

Continuity of care

Patients commonly highlighted the difficulty of finding a GP they felt they could consult with on an ongoing basis. Many attended high-throughput, bulk-billing practices for isolated issues in an episodic fashion, but did not develop sustained doctor–patient relationships. Patients frequently expressed the importance of having their own personal GP, but were unsure how to find one.

It’s not our doctor, it’s only, you have problem, you visit a doctor. He didn’t ask about previous visits, just some general questions. (P6)

This often meant that only acute health issues were addressed, while preventive care was neglected.

Individual factors

Interviewees reported considerable variability in how patients coped with the transition process. Those who transitioned to mainstream care more easily often had better English language proficiency, good general literacy skills, and greater independence and ability to self-advocate. Patients who experienced more difficulty tended to rely more heavily on asylum seeker–specific services, and often had more severe mental illness affecting their memory, concentration and organisational skills.

Understanding the health system

Almost all interviewees identified difficulty understanding the Australian health system as a major issue. Concepts such as the gatekeeper role of the GP, specialist referral processes and obtaining prescriptions were often unfamiliar to asylum seekers, particularly when newly arrived.

I feel … like a kid, not knowing very simple thing, it takes you time to find maybe in internet, and maybe you get to the wrong conclusion. I’ve never even thought about all of this. (P6)

Staff of asylum seeker–specific primary care services provided explanations to patients about relevant aspects of the health system as required, but there was no systematic process for conveying this information to all patients. Numerous interviewees suggested methods to improve patients’ understanding, such as an information booklet or workshops.

Mental health

The substantial levels of mental illness experienced by asylum seekers affected their ability to cope with the logistical aspects of the transition. High instances of PTSD affected concentration, memory and organisational abilities.

When someone’s really unwell, it affects their engagement, their capacity to actually connect with other people. It affects their memory and … [what] they can take in, it affects how much they can tolerate. (S2)

In addition to logistical barriers, mental illness affected patients’ ability to establish trust in unfamiliar health professionals. As a result, patients often returned to asylum seeker–specific services.

Social and financial stability

For many asylum seekers, issues such as accommodation and finances were more immediate than health issues, and hence took precedence over managing their transition into mainstream primary care.

[I am] solving problems for today, you know: work, job, accommodation. My son fell ill, that’s a problem, so we go to see doctor. (P6)

Social and financial circumstances affected living conditions, and subsequently affected patients’ physical and mental health, and their ability to interact with health services.

Numerous patients became eligible for Medicare but did not receive work rights. Despite transitioning to mainstream care, they continued to rely on the ASC for access to free medications (not incurring the copayments required under Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme).

ASC always helps with medications, that’s why I’m so grateful. I don’t have any money to buy, but ASC buys, I don’t have to worry. (P2)

This ongoing financial dependence on the ASC limited the ability of individuals to manage their own healthcare. It also placed strain on the finite financial resources and staff capacity at the ASC.

Discussion

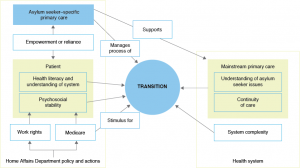

The reported experiences of asylum seekers and their healthcare providers demonstrate that transition to mainstream care is often difficult and confronting. Figure 2 outlines the interdependent factors affecting the success and ease of the transition.

Figure 2. Thematic map (click to enlarge)

Asylum seekers faced significant challenges transitioning into mainstream primary care because of their limited understanding of the health system and concurrent psychosocial issues. Staff of asylum seeker–specific health services played a central role in managing the transition and supporting mainstream providers, but this was not clearly defined and occurred on an ad hoc basis. Mainstream GPs often had poor understanding of asylum seekers’ health and psychosocial issues. This occurred in the context of a complex health system, Medicare instability for many patients and a lack of integration between services. These findings support previous research, mostly about refugees, which indicates that transition to mainstream primary care is a difficult process.6,9-15

Patients’ reluctance to transition has previously been attributed to a lack of clarity and coordination in the process, and a lack of available GPs.14 This study supports the notion that transition processes may be ill-defined and confusing for both patients and staff. It also contributes a deeper exploration of the reasons for reluctance from the individual’s perspective. Social and financial instability around the time of transition adversely affected asylum seekers’ abilities to cope with logistical aspects of the transition, thus increasing the likelihood of ongoing reliance on asylum seeker–specific primary care. This supports previous research that suggests that accommodation insecurity15-17, employment issues16-18, social isolation16,17,19 and fear of prosecution20 contribute to poor health by affecting continuity of care and ability to seek care.16

The comprehensive and welcoming nature of asylum seeker–specific services promotes acceptance, but also facilitates dependence in some patients. To reduce reliance on asylum seeker–specific services, patients need to be prepared to integrate into the mainstream health system well before the transition.7 This may conflict with providing for a patient’s immediate needs, and put a significant burden on asylum seeker–specific health services. However, not preparing patients for the transition creates an even greater burden, because patients end up continually reliant on resource-limited services.

The repeated gain and loss of Medicare benefits affected patients medically and psychosocially, reducing their ability to navigate the health system and cope with the transition process. Ensuring continuity of Medicare access would reduce physical and psychological harm to asylum seekers, and relieve some of the burden on asylum seeker–specific health services.

Mainstream primary care providers often lacked understanding of asylum seekers’ entitlements, and their health and social issues, as has been previously identified.15,21–23 Asylum seeker–specific services and PHNs must work synergistically to educate mainstream GPs about asylum seeker health issues and support GPs who have asylum seeker patients.

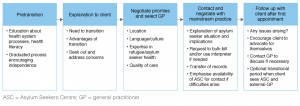

Figure 3 outlines a potential framework for the transition process, developed in consultation with ASC staff.

Figure 3. Potential pathway for transition (click to enlarge)

This study was potentially limited by recruitment through a single centre and the location of the interviews. Despite the small sample size, thematic saturation was reached. Significantly, this study investigates the views of asylum seekers themselves about the transition process. Future research could further explore the prevalence of these views among the asylum seeker population, and the perspectives of mainstream GPs receiving asylum seeker patients into their practices.

Conclusion

Transition from asylum seeker–specific to mainstream primary care is a complex process. Significant problems occur because of the nature of the relationship between patients and asylum seeker–specific services, deficiencies in the process of transition, psychosocial pressures, and lack of accommodation of asylum seekers by some mainstream providers. Asylum seeker–specific services need to increase understanding of the health system and health literacy among asylum seekers. Mainstream primary care providers need to be supported to increase their understanding of, and sensitivity to, asylum seeker health and psychosocial issues. This could be achieved through partnerships between asylum seeker–specific health services and PHNs.

Copyright:

© 2018 Fair et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Global trends: forced displacement in 2016. Geneva: UNHCR; 2017 [cited 2018 Jan 10]. Available from: www.unhcr.org/5943e8a34.pdf

- 2. Harris M, Telfer B. The health needs of asylum seekers living in the community. Med J Aust. 2001;175(11–12):589–92. PubMed

- 3. Hadgkiss E, Lethborg C, Al-Mousa A, Marck C. Asylum seeker health and wellbeing scoping study. Melbourne: St. Vincent's Health Australia; 2012 [cited 2016 Apr 1]. Available from: svha.org.au/wps/wcm/connect/cb7b96fc-6653-42ea-9683-749a184d3aed/Asylum_Seeker_Health_and_Wellbeing_Scoping_Study.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&%3bCONVERT_TO=url&%3bCACHEID=cb7b96fc-6653-42ea-9683-749a184d3aed

- 4. Asylum Seekers Centre. Asylum Seekers Centre annual report 2014–2015. Sydney: ASC; 2015 [cited 2018 Jan 10]. Available from: asylumseekerscentre.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/ASC-Annual-Report-2014-15.pdf

- 5. South Western Sydney Local Health District. Sydney: SWSLHD; 2017 June 16. NSW Refugee Health Service; 2017 Oct 31 [cited 2018 Jan 10]; [about 1 screen]. Available from: www.swslhd.health.nsw.gov.au/refugee/

- 6. Joshi C, Russell G, Cheng IH, Kay M, Pottie K, Alston M, et al. A narrative synthesis of the impact of primary health care delivery models for refugees in resettlement countries on access, quality and coordination. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:88. CrossRef | PubMed

- 7. Le Feuvre P. How primary care services can incorporate refugee health care. Med Confl Surviv. 2001;17(2):131–6. CrossRef | PubMed

- 8. Settlement Services International. Sydney: SSI. What is the Status Resolution Support Service? [cited 2018 Jan 12]; [about 2 screens]. Available from: www.ssi.org.au/faqs/humanitarian-services-faqs/127-what-is-the-status-resolution-support-service

- 9. Johnson DR, Ziersch AM, Burgess T. I don't think general practice should be the front line: experiences of general practitioners working with refugees in South Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;5:20. CrossRef | PubMed

- 10. Gould G, Viney K, Greenwood M, Kramer J, Corben P. A multidisciplinary primary healthcare clinic for newly arrived humanitarian entrants in regional NSW: model of service delivery and summary of preliminary findings. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2010;34(3):326–9. CrossRef | PubMed

- 11. Jensen NK, Johansen KS, Kastrup M, Krasnik A, Norredam M. Patient experienced continuity of care in the psychiatric healthcare system – a study including immigrants, refugees and ethnic Danes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(9):9739–59. CrossRef | PubMed

- 12. Lewis V, Marsh G, Hanley F, Macmillan J, Morgain L, Silburn K, et al. Understanding vulnerability in primary health care: overcoming barriers to consumer transitions through the primary health system. Canberra: Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute, Australian National University; 2013 [cited 2018 Jan 10]. Available from: files.aphcri.anu.edu.au/reports/Lewis.Final.Report.25.pdf

- 13. Cooke R, Murray S, Carapetis J, Rice J, Mulholland N, Skull S. Demographics and utilisation of health services by paediatric refugees from East Africa: implications for service planning and provision. Aust Health Rev. 2004;27(2):40–5. CrossRef | PubMed

- 14. McMurray J, Breward K, Breward M, Alder R, Arya N. Integrated primary care improves access to healthcare for newly arrived refugees in Canada. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(4):576–85. CrossRef | PubMed

- 15. Watters C, Ingleby D. Locations of care: meeting the mental health and social care needs of refugees in Europe. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2004;27(6):549–70. CrossRef | PubMed

- 16. Bhatia R, Wallace P. Experiences of refugees and asylum seekers in general practice: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:48. CrossRef | PubMed

- 17. Spike EA, Smith MM, Harris MF. Access to primary health care services by community-based asylum seekers. Med J Aust. 2011;195(4):188–91. PubMed

- 18. Lawrence J, Kearns R. Exploring the 'fit' between people and providers: refugee health needs and health care services in Mt Roskill, Auckland, New Zealand. Health Soc Care Community. 2005;13(5):451–61. CrossRef | PubMed

- 19. Wahoush EO. Equitable health-care access: the experiences of refugee and refugee claimant mothers with an ill preschooler. Can J Nurs Res. 2009;41(3):186–206. PubMed

- 20. Teunissen E, Sherally J, van den Muijsenbergh M, Dowrick C, van Weel-Baumgarten E, van Weel C. Mental health problems of undocumented migrants (UMs) in The Netherlands: a qualitative exploration of help-seeking behaviour and experiences with primary care. BMJ Open. 2014;4(11):e005738. CrossRef | PubMed

- 21. Begg H, Gill PS. Views of general practitioners towards refugees and asylum seekers: an interview study. Divers Equal Health Care. 2005;2(4):299–305. Article

- 22. Duncan G, Harding C, Gilmour A, Seal A. GP and registrar involvement in refugee health – a needs assessment. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(6):405–8. PubMed

- 23. Jensen NK, Norredam M, Priebe S, Krasnik A. How do general practitioners experience providing care to refugees with mental health problems? A qualitative study from Denmark. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:17. CrossRef | PubMed